Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

Many of my posts come from research to expand my understanding of geological sights and sites I’ve photographed but no longer know (or never knew) the detailed stories of. This time it’s some rocks north of Socorro, New Mexico, where Dave and Jen Wilson took me on one of my trips to New Mexico Tech as a Visiting Geologist for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in 2003.

An unconformity is a gap in the rock record. It may indicate non-deposition or erosion, or one of several special circumstances. This one clearly indicates erosion.

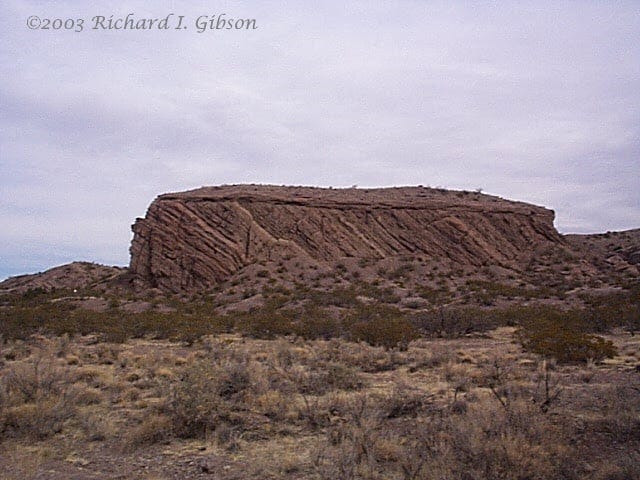

My photo at top shows a classic angular unconformity in a narrow, isolated mesa along San Lorenzo arroyo. The tilted rocks dominating the outcrop belong to the Popotosa Formation, a pile of volcaniclastic rocks nearly a mile thick in places. They were eroded from the Mogollon-Datil volcanic field, which erupted about 36 to 27 million years ago (Eocene-Oligocene time) in southwestern New Mexico (McIntosh and others, 1992, Time-stratigraphic framework for the Eocene-Oligocene Mogollon-Datil volcanic field, southwest New Mexico: GSA Bulletin 104:7, p. 851-871).

The Popotosa was eroded from that volcanic pile and deposited from 26 to 7 million years ago (Oligocene-Miocene) as conglomerates in alluvial fans, finer sediment in small streams, and playa lake deposits in closed basins that represent the initial sag that would become the Rio Grande Rift. The materials in the rocks are mostly volcanics and include some ash falls (Chamberlain, 2004, Geologic map of the San Lorenzo Spring 7.5-minute quadrangle, Socorro County, New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources OF-GM-86). My photo is about a half-mile from one of the reference sections of the Popotosa Formation in Cañóncito de las Cabras (Little Goat Canyon) in San Lorenzo arroyo.

Extension of the Rio Grande Rift proceeded with normal faults that dropped some parts of the basins down while leaving others high-standing. In this process, sometimes symmetrical grabens (fault-bounded troughs) develop, but often the faulting is more intense on one side than the other, resulting in half-grabens which typically display tilted rocks as one side moves down more than the other. That’s the origin of the tilted Popotosa beds in the photo. The dip (tilt) here is to the east, toward the axis of the rift.

After the tilted beds were eroded to a relatively flat surface (at least here locally) they were capped with much later sediments (500,000 years or so old, possibly as old as 1.9 million years ago – Pleistocene time) in a pediment or terrace deposit related to the ancestral Rio Grande River that developed as a through-going integrated river system connecting the formerly closed basins. The ongoing normal faulting that is continuing to widen the Rio Grande Rift today has tilted those beds slightly, but far less than the underlying Popotosa layers. Continued erosion left this small block exposed when the material surrounding it was removed relatively recently, after the deposition of the pediment or terrace sediments.

The contact between the two units, called an angular unconformity, tells us that the Popotosa had been deposited AND tilted AND eroded before the deposition of the overlying Pleistocene layers. That means the tilting occurred between about seven million (end of deposition of the Popotosa) and about 1.9 million years ago (the earliest time the overlying almost flat-lying beds were deposited).

You can also see a small fold in the left-hand part of the outcrop, a fold that probably developed contemporaneously with the tilting and faulting. It’s a little more visible in the old black-and-white USGS photo of the same mesa. The USGS geologist and surveyor who took the photo, R. H. Chapman, did most of his work from about 1890 to 1920, so that is the likely vintage of that old photo. Furthermore, junipers and mesquite and such plants grow slowly especially in arid country, and those near the base of the mesa in my 2003 photo are rather bigger than in the USGS photo, so that adds to the idea that the Chapman photo is pretty old. Also, look closely at the left side of the outcrop (near the fold) in the USGS photo and you can see a surveyor on horseback with a stadia rod. It’s been a while since USGS geologists traveled by horseback (more’s the pity). The label “Arizona” on the historic photo is an error.

My second photo shows a closer look at the tilted conglomerates of the Popotosa Formation. This is a sedimentary rock (a clastic rock, from a word meaning broken pieces), but the materials in it are mostly consolidated volcanics, solidified lava flows, ash falls, and other stuff, but broken into cobbles, pebbles, sand, and silt and redeposited by moving water. Such rocks are called volcaniclastic to differentiate them from “usual” sedimentary rocks that come from erosion of things like granite, metamorphic rocks, and other sedimentary rocks.

As I researched the Popotosa Formation, it was a small-world treat to find citations for work by Sigrid Asher-Bolinder (a compatriot in geology from my Indiana University days, and a student in the IU geologic field course in 1970, one of my T.A. years) as well as the late Elizabeth Brenner-Tourtelot (Younggren), one of the long-time stalwarts of the Tobacco Root Geological Society.

Our Hutton's Unconformity here in Southern Scotland has the younger rocks on top Old Red Sandstone of Devonian age, quite a few hundred million years older than your one! It was the formation that first led to realisation of the great age of the earth – clearly a lot older than the 6,000 or so years in the Bible

Now that is text book!