First in a series

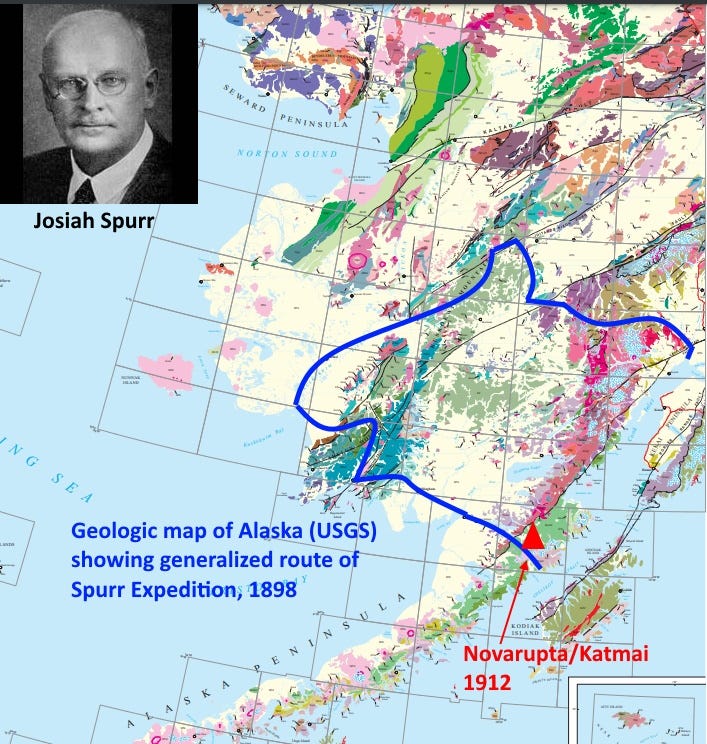

When 28-year-old Josiah Spurr led a 1425-mile journey through southeastern Alaska for the US Geological Survey in 1898, it was a time of proliferation of geological jargon – a new word appeared for some of the slightest variations in rocks.

Many of the rock names Spurr coined did not survive long, so thankfully we don’t have to look up the meanings of tarantulite, belugite, tordrillite, esmeraldite, and others, but one of his new words has more or less survived. Alaskite is a type of granite that’s very light in color, with few of the dark minerals such as biotite and hornblende that typical granite does have.

Spurr defined the rock as a granite with mostly feldspar and quartz. It’s pretty common, and my photo here is of a chunk of alaskite from the Boulder Batholith near Butte, Montana USA. Today some would call it leucogranite (from Greek leukos ‘white’), but most petrologists probably understand what “alaskite” means.

The Boulder Batholith also contains a variation on granite called aplite. Aplite is also a rock that is dominated by quartz and feldspar, so it’s usually light colored. The word is from Greek aploos ‘simple,’ for that simple composition, and was probably first used in 1823 by German mineralogist Karl Cäsar von Leonhard (1779-1862) for granite with no mica.

So why didn’t Spurr just use the well-established word aplite? The original use of aplite may or may not have implied a grain size for the quartz and feldspar, but over time it seems that it evolved into the word for a quartz-feldspar rock that was also fine-grained, on the order of a few millimeters. Spurr’s alaskites include rocks that were the typical coarse crystals of granite, more like a half centimeter or more across.

I think most petrologists would also understand what aplite means, along with alaskite. Rightly or wrongly, I think there is a connotation that the fine-grained nature of aplite, its texture, is more important than its composition (so you could have some small dark grains in aplite), while alaskite is mostly a composition term, irrespective of texture. By the definitions we have, there would clearly be some overlap: you can have a rock that’s both, or one but not the other. You might be able to call a rock aplitic alaskite, but I bet (I hope) no one would do that; they’d just say “fine-grained alaskite” or let “aplite” stand alone meaning fine-grained light-colored granite. Some parts of the Boulder Batholith around Butte are mapped as aplite.

Spurr’s geological career led to him being honored in the names of a volcano in Alaska, a crater on the moon, and the mineral spurrite. He died in 1950.

Parts of Spurr’s account of his team’s journey through uncharted territory (they made their own topographic maps) read more like an Indiana Jones story than a scientific report. The team arrived at Tyonek, a native village on Cook Inlet (settlement at Anchorage did not begin until the 1910s), on April 26, 1898, but could not head upriver until the ice began to break up on May 4. After reaching the Sushitna (now spelled Susitna) River mouth, their intended portal to the interior, the weather forced a further delay until May 20 when the river became sufficiently ice-free for them to travel. Even then, after they

“… had gone several miles, we were surprised by a solid wall of ice bearing swiftly down upon us, and we had only time to throw our load upon the banks and drag the boats out of the water before the ice jam swept past, piling over upon the banks in places and grinding off trees.”

“As soon as the jam had passed we proceeded on our way, dodging the loose cakes of floating ice; but on this day and the next we had the same experience several times. We found out afterwards that the ice had broken first at the delta and then by successive stages higher up the river, but that most of the river was unbroken at the time we started to ascend. On the first day a floating cake of ice broke a hole in one of our boats, which was promptly beached and repaired. On the 21st of May, arriving at a point just below the Sushitna trading station, the post maintained by the Alaska Commercial Company for the purpose of trading with the Indians, we found that the river was blocked by a tremendous ice jam. The next morning, however, the jam not yet having broken, we succeeded in finding a channel through and arrived at the trading post. At this time the mosquitoes first began to be annoying.”

For me, the simple title of this 1900 USGS Annual Report evokes the wonders of being a geologist at the end of the 19th century: “Explorations in Alaska in 1898.” Besides Spurr’s report, the 509 pages contain papers by W. C. Mendenhall, namesake of the Mendenhall Glacier and fifth director of the USGS; another by Alfred H. Brooks, who discovered and explored the range in Arctic Alaska that bears his name; and another by George Eldridge, whose team accurately measured the height of Mt. McKinley (Denali) and mapped a glacier descending from Denali’s flanks that was named for Eldridge.