Agate

Wild variety

Agate is usually defined as banded chalcedony (fine-grained quartz), typically with a wide variety of colors due to various impurities and inclusions. But neither is all banded chalcedony agate, nor are all materials called agate banded. I’d say usually, such non-banded varieties would technically be called other kinds of chalcedony varieties despite common use of the word “agate.” There are dozens of varieties that often get specific names, though they are mostly just for lapidary convenience and marketing.

The banding is probably most commonly due to alternations in the impurity content of the crystallizing silica, but variations in the way the silica fibers grow, even in essentially pure silica, produce banding as well. Chalcedony in agates can crystallize with molecular-scale differences in size and orientation (much of it is actually fibrous at that level) that generate changes in translucency that we perceive as banding. At that level, the way the silica crystallizes makes for variations that are far more complex than simple alternating bands of variable composition.

Today I just want to share a few examples.

This specimen in the top photo is probably from a famous locality in Chihuahua, Mexico, Rancho Coyamito. If that is indeed the source and this is the variety called Coyamito agate, then it’s likely that the finger-like protrusions were once spears of aragonite (calcium carbonate) growing in a gas bubble within a rhyolitic flow of volcanic rocks. The aragonite got coated by thin layers of chalcedony and later the aragonite dissolved. The sites of the aragonite crystals were eventually filled in by more chalcedony. Cat. No. 1036

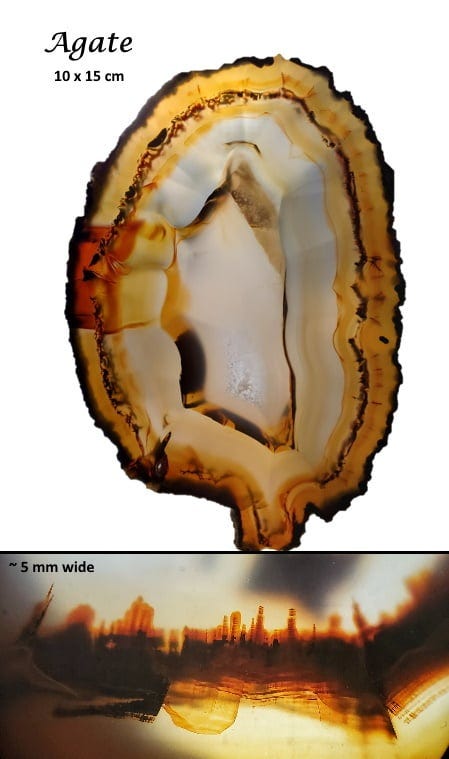

This 10x15-cm agate slab is probably from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, where the chalcedony (fine-grained quartz) fills unusually large vugs or cavities (more technically, amygdules, fillings in former gas bubbles in lava) in the Parana Basalts, which erupted about 132 million years ago as an aspect of the early rifting of the South Atlantic Ocean. Agates are sometimes distinctive enough that they can be attributed to a particular locality, but this one is not.

This one shows some of the “iris effect,” a chatoyancy in the bands, that is technically called “wall-lining banding.” It’s a consequence of the varying size and orientation of the molecular-scale chalcedony fibers I mentioned above, variations that occur cyclically and probably change somewhat with each new nucleation front, or band (Lu and Sunagawa, 1994, Texture formation of agate in geode: Mineralogical Journal: 17: 53-76). The appearance is complicated by compositional and inclusion variations as well. The geometry of the impurity zones can be incredibly complex, as you see in the close-up at the bottom.

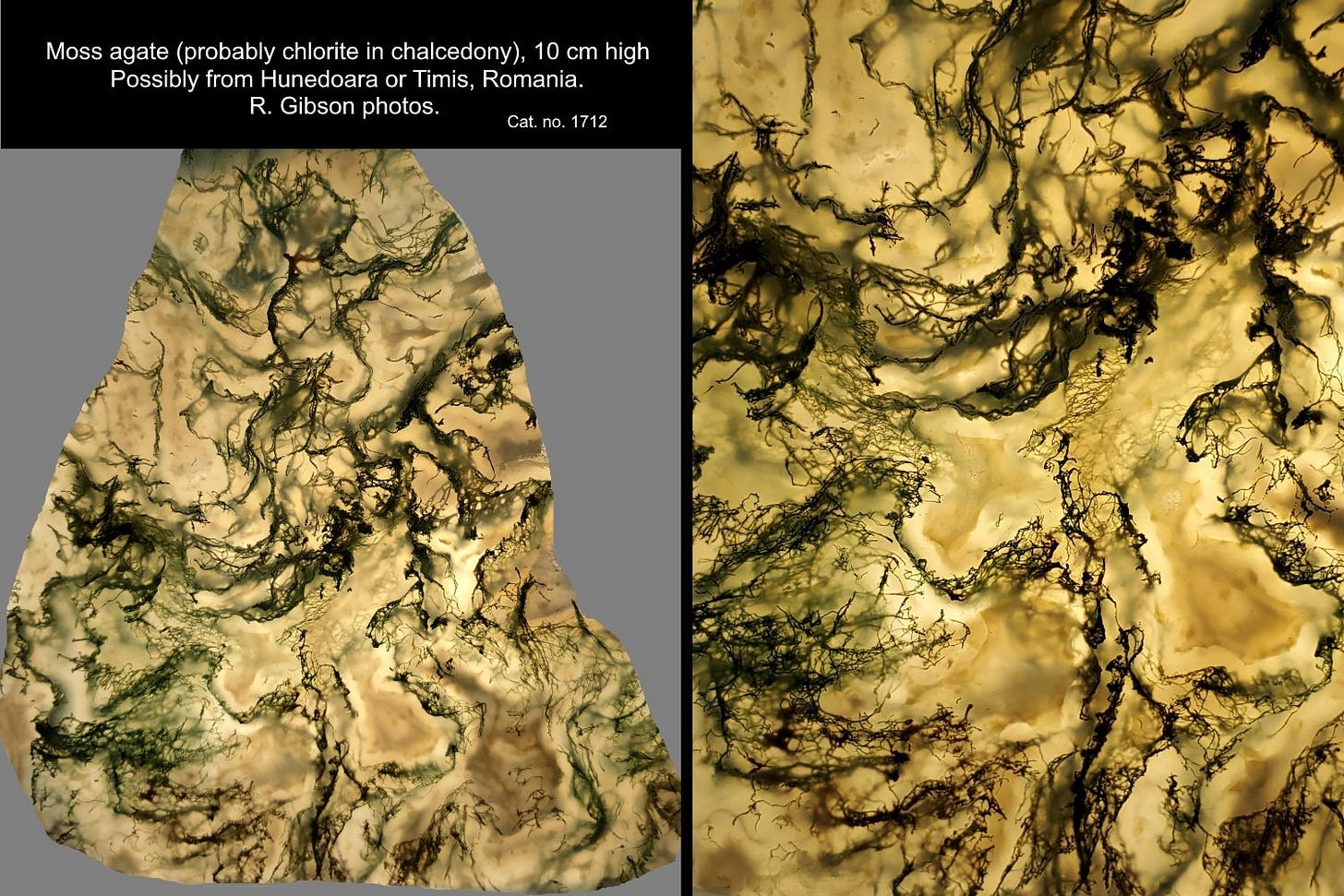

The best name for this polished 10-cm slab is probably moss agate, although it has a different look than much of the typical bushy, arborescent moss agate you see, and it would not be considered agate in the strict sense of banded, fibrous chalcedony. It’s really just translucent to transparent chalcedony with inclusions. I not certain, but it’s most likely that the green filaments are strands of some chlorite mineral included within translucent chalcedony, microcrystalline quartz.

Note that “moss agate” has nothing to do with moss or any other plant. The included material is all inorganic mineral matter. Chlorite is the name of a group of micaceous magnesium-iron aluminosilicates; clinochlore (Mg) and chamoisite (Fe) are the most common members of the group, but it would take analysis to determine which (if either) this stuff is, and most likely it’s somewhere in the solid solution series between those two end members. That means it probably has both magnesium and iron in its composition. Chlorite minerals are typical in low-grade metamorphic environments, and often become included in late-formed quartz.

This came out of my father’s lapidary material and I suspect that he polished it. The locality is unknown to me, but rather similar material comes from a couple places in Romania: Lapugiu De Sus in Timis County, and Hunedoara County. If anyone has more experience and knows of likely localities for this material, I welcome your thoughts. Cat. No. 1712.

According to Native American tradition in Oregon, Thunder Spirits who lived on Mt. Hood and Mt. Jefferson battled, throwing round rocks filled with beautiful agate designs inside: Thunder Eggs.

The more prosaic explanation is that there were gas cavities within some of the lava flows of central Oregon, and when water percolated into the cavities, leached minerals deposited in a rim inside them. Such a first lining would also seal the cavity – fully or partly – so that any remaining water would sit there like a quiet pool, evaporating or seeping out slowly.

Changes in mineral content over time as the waters evaporated meant that horizontal layers of fine-grained quartz (chalcedony) would develop with an array of colors reflecting the variable mineral content. Sometimes an earthquake or other event might tilt the rock, so you can end up with two (or more) sets of mineral bands at angles to each other, but probably more commonly, as in my specimen, the last remaining stuff in solution precipitated out and grew into and filled the last remaining open cavity. That’s the likely explanation for the roughly triangular area at the top of my specimen, above the horizontal lines, where the more irregular filling is found.

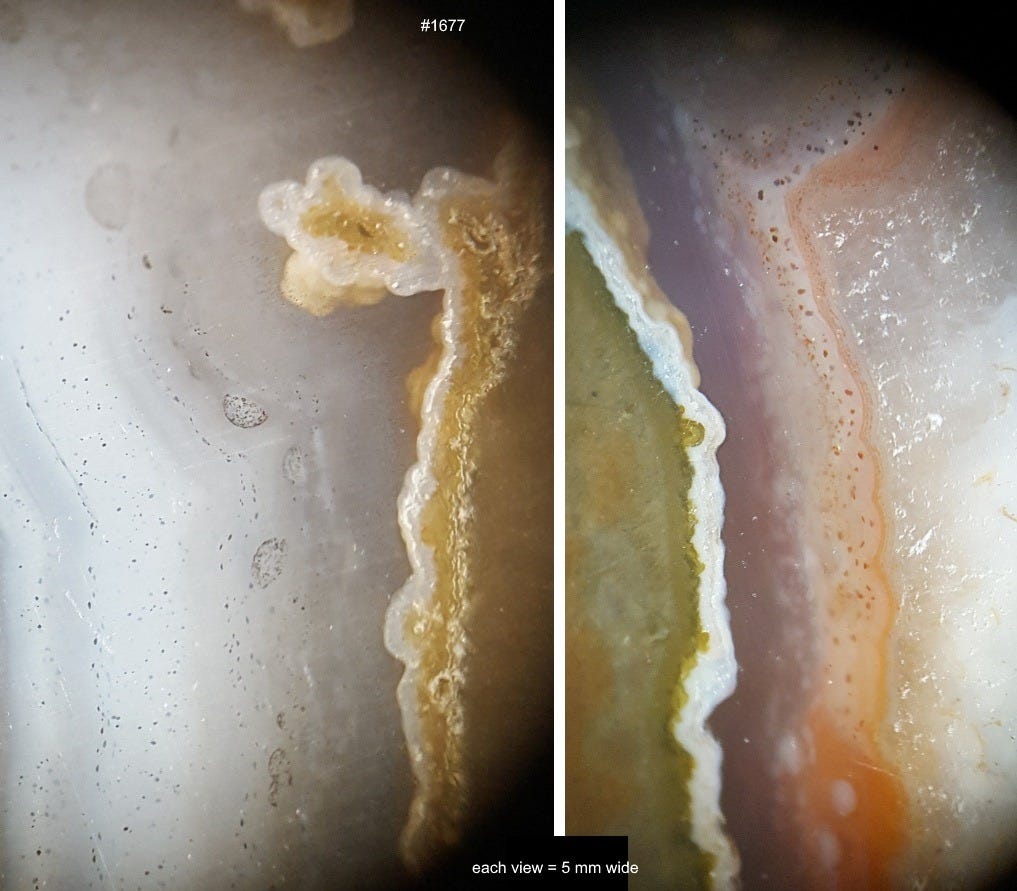

The details of the rims in the microphotos above, from the same Thunder Egg, show some of the variety of crystalline material, ranging from transparent to green in color. The tiny red and black inclusions are most likely hematite (iron oxide), and in the left-hand microscope view you can see how those little crystals seem to have coated bubbles, or maybe just botryoidal (“grape-like”) blobs of earlier-formed chalcedony.

The specimen is from Oregon, probably the famous Richardson Ranch locality. If you want some jargon to enhance your day, the cavities are called lithophysae, from Greek words for stone and blow (sometimes translated as “stone bubbles”), suggesting that the cavities came from gases blown into the molten rock.

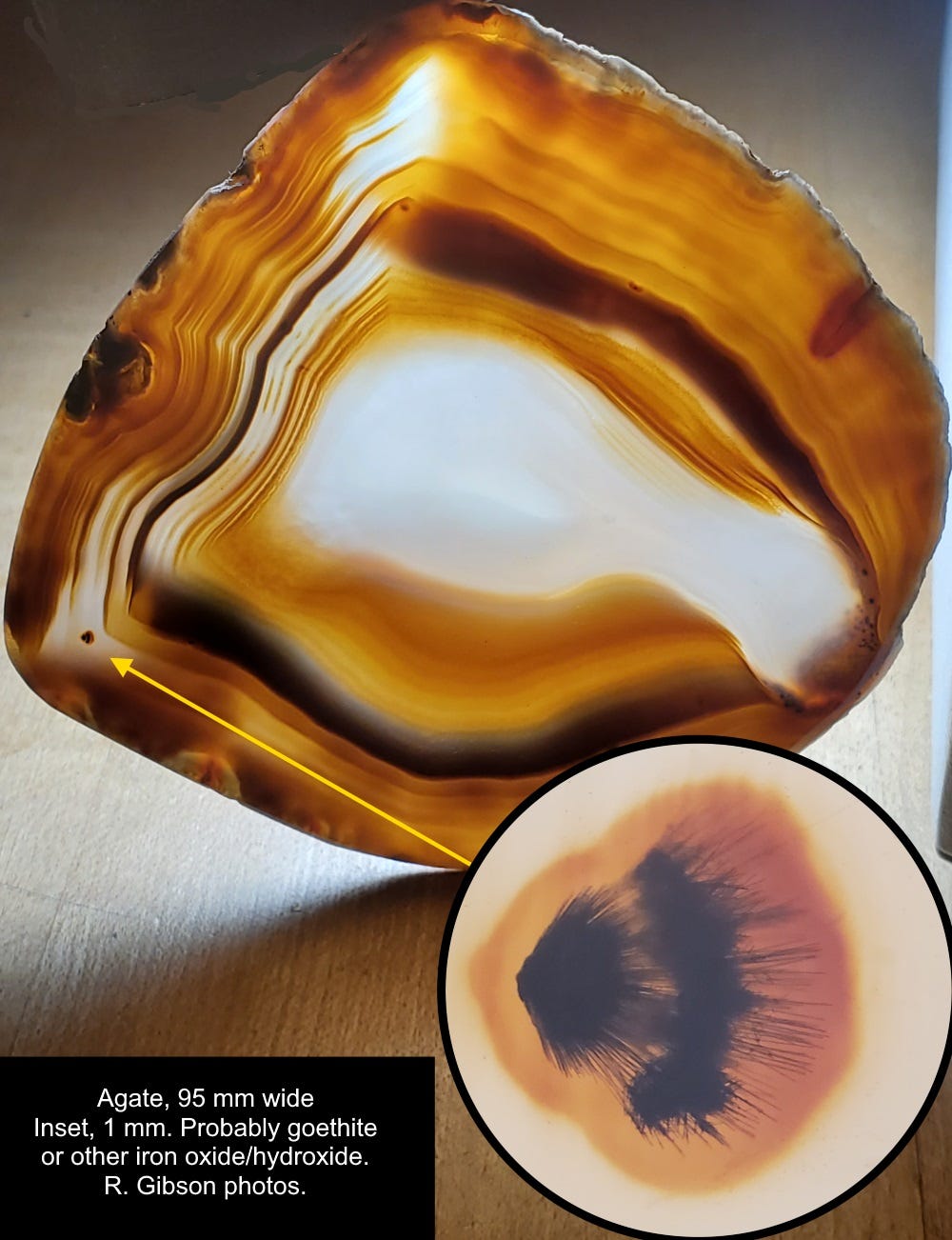

The location for this one is unknown, but Mexico is a good guess. Much of the banding here is related to inclusions in specific zones. Goethite (named for the poet Goethe), iron hydroxide, often forms needles like those in the inset, but they could be any of several iron or magnesium oxides or hydroxides. Why just one little blob of goethite needles? I don’t know.

The word “agate” probably comes from Greek “Akhates,” the name of a river in Sicily where such stones were found, although it is possible that the river was named for the rocks. “Chalcedony” is derived from the name of the ancient Greek town Chalkedon in Asia Minor, today the Kadıköy district of Istanbul, Turkey. “Amygdule” is from a Greek word for “almond,” from the typically almond-shaped form of the filled gas bubbles.

I enjoyed the etymology of the words, very helpful, and the short explanations. There are books on agate formation. (Sorry, I'm not THAT interested, I'm just curious. lol.) So, thanks

I’m going with botryoidal (grape-like) as my word of the day. Also ruminating on the idea that Goethe has a mineral named after him.