Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

Simple aluminum oxide, Al2O3, makes one of the hardest minerals, corundum, 9 on the hardness scale just below diamond at #10 (but far lower than diamond in terms of absolute hardness). Combine that hardness with the colors created by the presence of trace elements and you have some of the most coveted gemstones in the world: blue sapphire and red ruby.

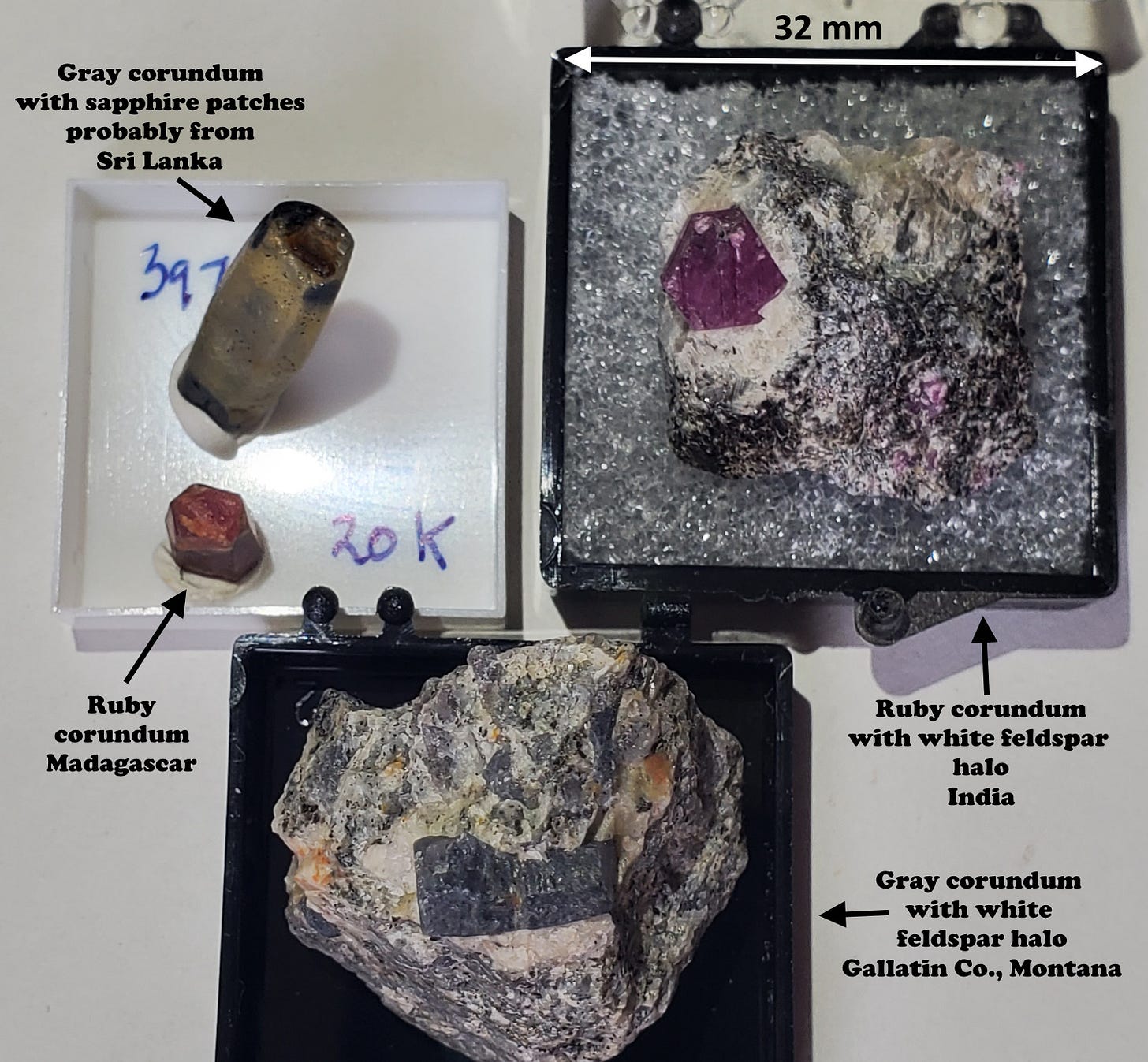

“Sapphire” is usually taken to mean blue, but it’s really any color other than red, and the distinction becomes subjective somewhere in the purple range. And by no means are all sapphires and rubies gemmy, meaning relatively transparent and without fractures. None of my specimens here would be worth cutting into a gem. The large hexagonal ruby crystal is too opaque and is worth more as a specimen than as a gem; the little one is an interesting crystal, but so dark as to be useless as a gem (it cost me 50¢ in 1962). The others aren't even very colorful.

The red color in rubies results from traces of chromium replacing some of the aluminum. Chromium in rubies is commonly around 1% to 3% by weight but concentrations up to 10% or more are known. Pure chromium oxide, the analog of corundum, is the rare mineral eskolaite, and it is typically black to dark green. Red ruby is clearly a result of the traces of chromium in the corundum, and more is not necessarily better from the ruby point of view.

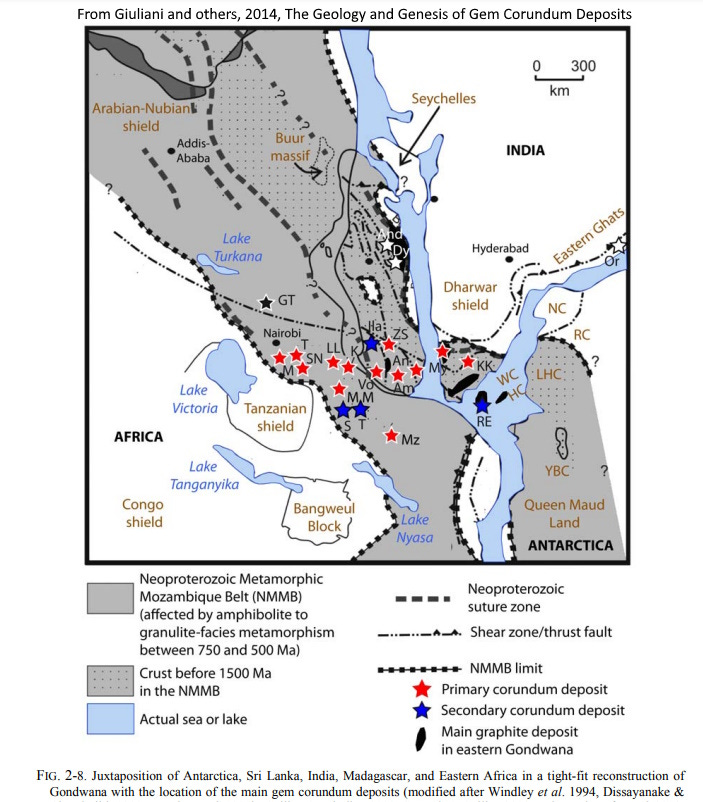

I only have “India” for the location of my red crystal (and the little one is just “Madagascar”) but it is certainly from the southern tip of India, which was in close juxtaposition with Sri Lanka, Madagascar, and Tanzania, three other important ruby areas, when they amalgamated in the formation of Gondwana during the Pan-African Orogeny about 600 to 500 million years ago. Metamorphism related to continental collisions generated the corundum. (See the map above, which is from Giuliani and others, 2014, The Geology and Genesis of Gem Corundum Deposits: in The Geology of Gem Deposits, Vol. 2: Mineralogical Association of Canada, L.A. Groat, ed.)

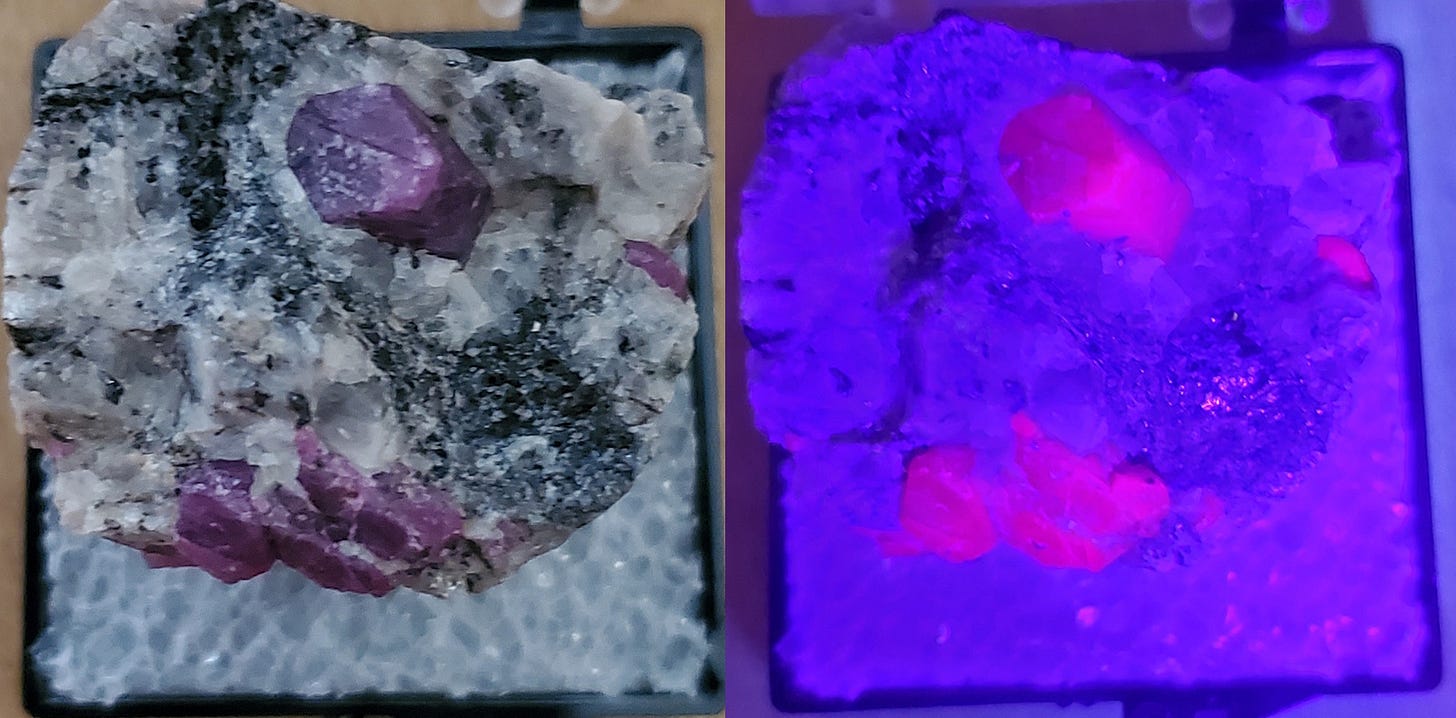

I think the origin of the “dehydration halo,” the white zone surrounding my ruby crystal, is complex and poorly understood. A recent discussion on MinDat, the online database, involved several knowledgeable experts and I don’t think a full consensus was achieved.

One idea is that if the silica content in the original sediment was low, metamorphism tends to form corundum rather than common feldspars, so the ruby might reflect patches of low-silica material in the protolith (the original rock), leaving a halo of more silica-rich white feldspar. Others support a historic view that hydrous muscovite in the early metamorphic rock (a gneiss or schist) was progressively dehydrated, with excess aluminum going into corundum, leaving behind (surrounding it) a “dehydration halo” of white feldspar.

Another idea is that corundum formed first, consuming aluminum until the ratio with silica was appropriate to generate the surrounding feldspar halo, and then even later, things like muscovite did form further away from the corundum crystals.

One issue with all of those thoughts is that while the white feldspar haloes are common around rubies, there are often some with no such haloes. In any event, to me, while acknowledging the beauty of the well-formed ruby crystal, the rest of the story is actually more interesting.

Ruby often fluoresces, so that a relatively dull reddish color (or purple like my example above) becomes a more intense red (under mid-wavelength ultraviolet light at right). Fluorescence is probably a further aspect of the chromium ions in the corundum, the same thing that makes ruby reddish in visible light. This specimen also shows haloes around the rubies.

Corundum was originally named "corinvindum" in 1725 by John Woodward, based on the Sanskrit word kuruvinda for ruby. Richard Kirwan used the current spelling "corundum" in 1794. “Ruby” is from Latin rubeus, red, and “sapphire” is from Greek sáppheiros, meaning “precious stone, gem,” but probably from a Hebrew or Sanskrit precursor. The Greeks probably used the word mostly for the blue rock lapis lazuli. Eskolaite was named for Pentti Eskola, a well-known Finnish metamorphic petrologist.

I'm interested in your local Gallatin piece. Long ago I learned there was corundum somewhere near the mouth of Gallatin Canyon. Yours is the first actual sample I've ever seen. I know the mouth of the canyon is Archaean metamorphic--do you know anything more about the geology of the corundum deposit? I assume it's back in the hinterland somewhere. Very rugged country. Good explanation for formation of the crystals. Thanks.

Cool stuff, thank you.