Año Nuevo Point, between San Francisco and Santa Cruz on the coast of California, is famous as the wintering ground for elephant seals. I’m sure the seals care more about the sandy beach than the rocks, but it’s the rocks we’re going to today.

The point itself is to my right in the east-looking vantage of my photo here. The rocks there and in the surf beyond the seals are composed of the Miocene Monterey Formation, deposited as clay and silt about 8 to 14 million years ago. The water was nutrient-rich, supporting exceptional amounts of diatoms, microscopic single-celled algae that secrete silica shells. In the Monterey formation, tons and tons of dead diatoms have produced some of the thickest layers of diatomaceous earth and harder lithified equivalents anywhere in the world. (There are a couple pages on diatoms and their role in filters for things like beer, corn syrup, and fruit juice, in my book What Things Are Made Of, p. 108-110, if you are interested in more information.)

The cliffs in the distance across Año Nuevo Bay in my photo are younger (Pliocene, 5.3 to 2.5 million years old) rocks that lie on top of the Monterey Formation. But in the treed hills just beyond the cliffs and grassy slopes, you get back into the Monterey Formation. The Monterey and the Pliocene rocks there are juxtaposed along the active San Gregorio Fault, a right-lateral strike-slip fault that’s part of the San Andreas fault system. The most recent major (magnitude about 7.1) earthquake on the San Gregorio fault occurred between 1270 AD and 1775 (Simpson and others, 1997, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 87 (5): 1158–1170).

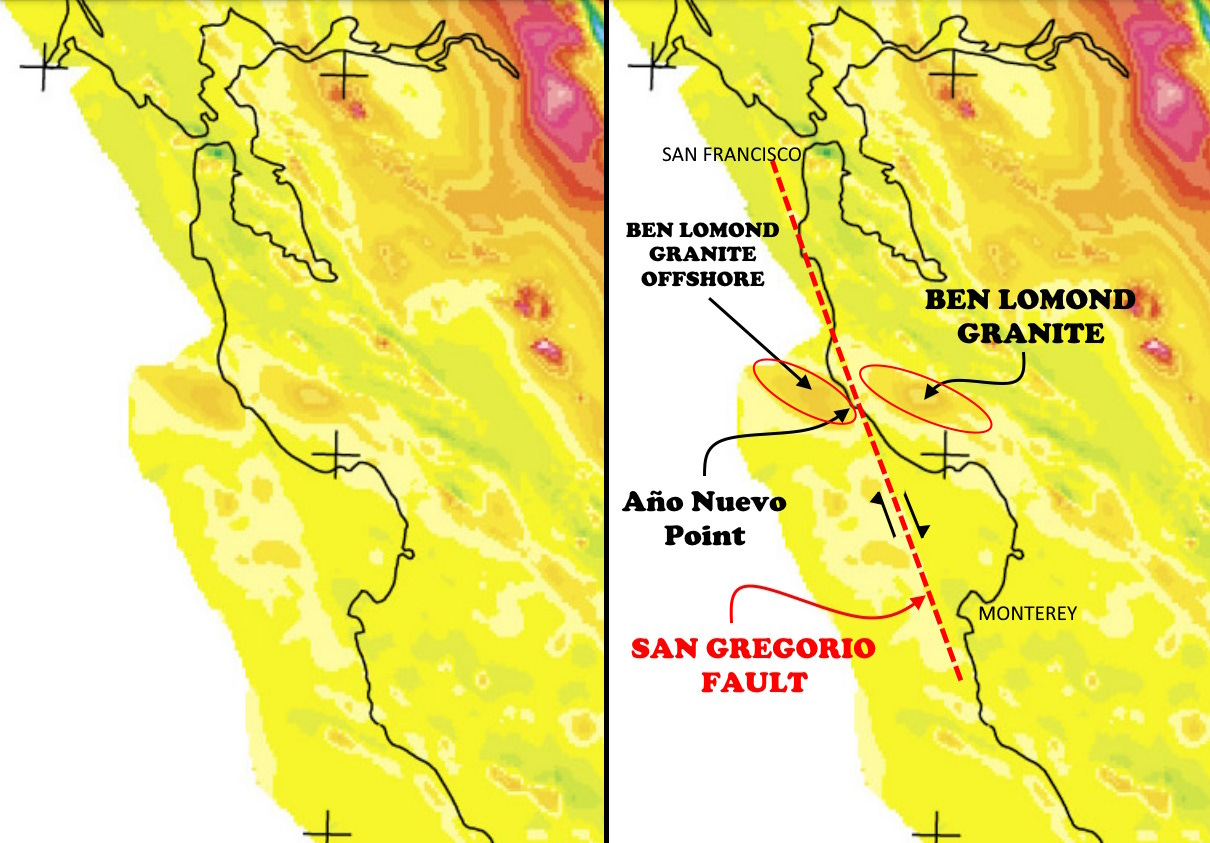

The San Gregorio Fault, like the San Andreas, is part of the accommodation of stress in western North America where the North American Plate (mostly continental in nature out there) is interacting obliquely with the Pacific Plate, which is mostly oceanic, but in California the Pacific Plate carries a sliver of more continental material. That material is sliding northwestward along the San Andreas system relative to the North American Plate. It’s not one single smooth fault, although the San Andreas is sort of the master feature. The break along the San Gregorio Fault is one of the ways this oblique sliding is accommodated. The map above from USGS shows the splaying nature of the major faults.

I know you can’t tell from the photo, but the Monterey Formation rock layers in the surf have been tilted to close to vertical by all the faulting. The San Gregorio Fault cuts a magnetic anomaly that characterizes the granite in the Ben Lomond Mountains east of Año Nuevo, but which the magnetic data show continues quite far offshore, offset about 60 miles (100 km) by the fault. But there’s a problem: the apparent offset of the magnetic feature representing the Ben Lomond Granite (and its inferred continuation offshore) is in a left-lateral sense, as expressed in the two ovals in the map at right above. The known offset on the San Gregorio Fault is right-lateral, shown by the arrows along the fault. This may mean that there was different movement on the fault at some previous geologic time. Figuring that out and its implications was one of my first projects when I worked for Aero Service Corp. in Houston in 1975. It wasn’t really very difficult to identify the fault position, given the prominent linear nature of the magnetic anomaly (seen in the map above) and its excellent correlation with onshore mapped faulting, but trying to decipher the history was a lot more complicated.

Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno (c. 1548–1624) sighted Año Nuevo Point on January 1, 1603. The point he saw has since become separated from the mainland by erosion, and is now Año Nuevo Island, about a half kilometer off the present-day point.

And full disclosure, I went there in March 1988 to see the elephant seals, not the rocks.

Very nice, as always. I visited the point to see the (amazingly odiferous) elephant seals in 2007, during a trip to visit our son serving in the Navy at the Port Hueneme Seabee base. On the same visit, we drove through Carrizo Plain NM and visited the Wallace Creek site showing the offset dry wash channel at the San Andreas Fault.