Baku

Half the world's oil in 1900

The Caucasus Mountains, between the Black and Caspian Seas, hold some of the most important and early-produced oil provinces in the world. This area is part of the Alpine-Himalaya collision between pieces of Gondwana and the southern margin of Eurasia. Specifically, it’s the northern prong of Arabia that’s squeezing small bits of continent, more or less eastern Anatolia (Turkey) and part of the Iran block, which themselves were part of the Cimmeride continent, and all that is being pushed into the south side of Eurasia.

Geographically, the Caucasus is taken as the boundary between Europe and Asia, and it contains some high mountain peaks, including Mt. Elbrus, a dormant volcano that reaches more than 5,600 meters above sea level, more than 18,500 feet. It last erupted about 2,000 years ago, showing that this area is still tectonically active.

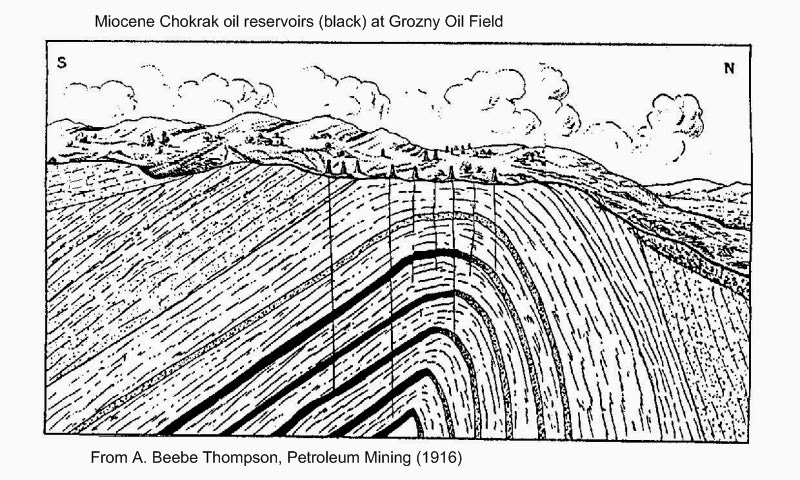

One of the effects of the ongoing Alpine-Himalayan collisions was the development of fold belts along and within the Caucasus Mountains complex. Rocks of Miocene age were pushed into large asymmetrical folds, anticlines and synclines with strata arched upward and downward, respectively. This shows certainly that the tectonic action was going on after the Miocene rocks were laid down, since they are involved in the folding. This isn’t a surprise, since we know the collision is still going on today. The early Miocene rocks were probably folded later in Miocene time, 5 to 15 million years ago, and in the Pliocene, 2 to 5 million years ago.

These anticlines trap lots and lots of oil. Oil was known in the area around Baku from the time of Marco Polo, and was supposedly used by locals for lubricants and fuel in the time of Alexander the Great. Baku oil was produced in quantity from hand-dug wells in the 1830s, and the world’s first paraffin factory began there in 1823. The first mechanically-drilled well in the world was drilled at Baku in 1846, 13 years before America’s first oil well in Pennsylvania, in 1859. By the 1870s, oil demand was surging worldwide, and outside investors came in to develop the oil fields around Baku. Two of the many fortunes that came from Baku oil were those of the Nobels, of Nobel Prize fame, and the Rothschilds. In 1900, half the world’s oil was coming from Baku, much of it from rocks of Miocene and Pliocene age, geologically young at less than about 23 million years old.

Further west along the northern front of the Caucasus Range, additional fields were discovered. Grozny, in Chechnya, became Russia’s #2 source of oil until after the Revolution in 1917, and the Grozny area still produced about 7% of the Soviet Union’s oil as late as 1971. The Grozny field is in an anticline in Miocene rocks, with multiple sandstone reservoirs with impermeable shale seals. The Caucasus oil was a major target of Hitler’s forces in World War II, and it still plays a significant role in the geopolitics of the region.

It’s no surprise that this oil was found so early, because it is practically at the surface in many cases, or just a few feet beneath the surface in the relatively young Miocene and Pliocene rocks. Marco Polo reportedly saw a natural gusher of oil. The organic rich source rocks are largely of Miocene age, called the Maykop Suite. There was a restricted seaway extending through this region, on the north side of the approaching continental blocks before they collided to raise up the Caucasus, and the marine carbonates of the Maykop Suite were deposited there. By Pliocene time, just four or five million years ago, the region became isolated from the sea, and rivers brought sandy sediment into the basin. Some of the most productive reservoirs around Baku are from Pliocene rocks deposited in deltas around the margins of the South Caspian Basin, which is an entrapped bit of old Tethys Ocean floor. The ongoing tectonic activity has created plenty of traps for the oil.

In the South Caspian, there’s about 20 kilometers of sediment on top of whatever is beneath it – and that depth, and lots of studies, indicate that the South Caspian is underlain by a piece of oceanic crust. It might be a left-over piece of the Tethys Ocean, entrapped between mountain belts, or it might be something else (the core of a back-arc basin, or an oblique rift within shear fault zones). Much of the Black Sea is something similar.

The mountain belts that entrap the South Caspian basin are evident on the magnetic map shown here (data used in part of my 1990 tectonic interpretation of the magnetic map of the former Soviet Union). They are the linear high-low bands that cross the map (and the Caspian Sea) from northwest to southeast, blue lines on the map. They record a long history of mountain building that resulted from slices of Gondwana crashing into this part of Eurasia.

Azerbaijan, where Baku is located, still produces about 600,000 barrels of oil per day, about 6% of what the US produces. But it’s only about the size of the state of Maine. US oil consumption is such that we still import some oil from Azerbaijan. It’s been sporadic (not every month) since about 2018, but the last reported month of imports, September 2023, the US imported about 7,000 barrels per day from Azerbaijan, trivial in terms of US consumption (about 20,000,000 barrels per day), and one of the least of the 55 or so countries that supplies the US with oil.

Thanks for thoughtful reply! Extracting and burning all that oil would have calculatable effect in terms of global warming - could work that out approximately but am currently hiking through the Pyrenees foothills!

No idea oil was laid down so recently. Would sequestration of this much oil cause noticeable global cooling?