This stuff that looks like yellow paint spatters is bindheimite on tetrahedrite from the Black Pine Mine near Philipsburg, Montana. If you never heard of bindheimite, well, neither did I until maybe four years ago. But it’s probably fairly common.

Chemically it’s lead-antimony oxide, and it occurs in oxidized zones of lead-antimony sulfide deposits. Black Pine has plenty of antimony, and certainly a decent amount of lead. The color may be pretty, but it seldom makes nice crystals and despite study since 1792 it’s not well defined. It may not hold the record for name variations over time, but it must be close.

Johann Jacob Bindheim (1750-1825) was the German chemist who first analyzed the material, in 1792. He apparently did not name it. In 1800 another German described it with the name bleiniere from the root blei (lead in German) and niere, kidney, for its sometimes reniform shape. By 1847 it was called stibiogalenites. Stibio- is from Latin for antimony, whence its element symbol, Sb, plus galen-, Latin for the ore (or smelter product) of lead, which shows up in the mineral galena, lead sulfide. Latin for lead itself is plumbum, the source of lead’s element symbol, Pb, and the root of the word plumbing because water pipes were made of lead in ancient Rome, and Flint, Michigan. Thanks, Romans.

In 1849, 1859, and 1863, this yellow substance became successively bleinierite, moffrasite (named by French geologist Alexandre Félix Gustave Achille Leymerie for a guy named deMoffras), and blumite, for Johann Reinhard Blum, mineralogy professor at the University of Heidelberg.

Eventually, in 1868 James Dwight Dana (The System of Mineralogy, 5th ed.) referred to it as bindheimite, naming it for its original analyst. Monsieur Adam (a member of the Société Minéralogique de France known only by his surname, even to close friends) called it pfaffite in 1869, for Christoph H. Pfaff, a German physician, chemist, and physicist who at age 28 in 1801 had become prominently involved in experiments with electricity, earning the admiration of Alessandro Volta (Krag and Bak, 2000, Christoph H. Pfaff and the controversy over Voltaic electricity: Bull. Hist. Chem., 25:2, p. 83). Confusingly, pfaffite was also used as a name (by J.J.N Huot in 1841) for a quite dissimilar mineral named by Pfaff as bleischimmer, “shining lead,” that ultimately became jamesonite, Pb4FeSb6S14. After all that, the name bindheimite seems to have stuck.

Until 2010, when the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) redefined the pyrochlore supergroup, and a study of bindheimite resulted in it being discredited as a mineral. Until 2013, when another study led to it being reinstated as an IMA-approved mineral species but listed as ‘questionable.’

Also in 2010, following the suggested nomenclature for the pyrochlore supergroup, a new mineral was described and named oxyplumboroméite, the lead end member of the roméite series. Oxyplumboroméite and bindheimite have the same chemical formula, Pb2Sb2O6O, and essentially identical crystallography and (within the limits of the poor definition of bindheimite) other properties that would say they are probably the same thing. Monimolite (from a Greek word for stable, because it is decomposed with great difficulty) is another unapproved mineral species that may or may not be identical with oxyplumboroméite.

So, although the IMA apparently lists bindheimite as ‘valid’ and ‘approved,’ albeit questionable, some sources say it’s not approved (although also referring to it as a mineral).

For my purposes I’m calling this bindheimite, with an asterisk noting the oxyplumboroméite connection. I’m betting they are identical, when it’s all said and done. Besides, everything I wrote here won’t fit on the label in this three-quarter-inch box.

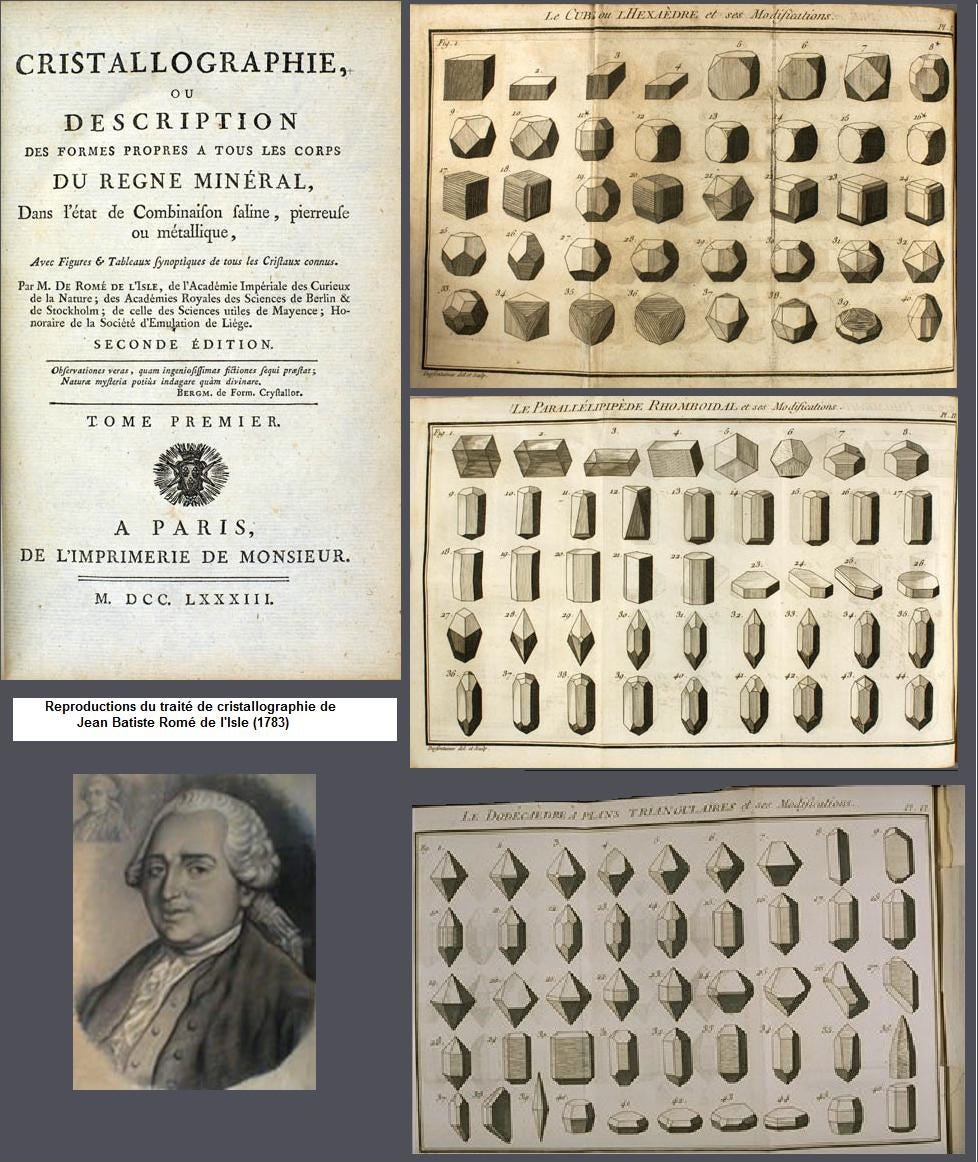

Roméite was named in 1841 by French mineralogist Augustin Alexis Damour (1808-1902) for Jean-Baptiste Louis Romé de L’Isle (1736-1790), another French mineralogist and pioneering crystallographer. The revisions in nomenclature mean that since 2010 roméite has not been a discrete mineral, but is a group including oxyplumboroméite and others. Romé is usually considered to be one of the fathers of modern crystallography.

The tetrahedrite upon which the yellow bindheimite is deposited is the main ore of silver at Black Pine, although it’s not a silver mineral per se: the silver is often incorporated in the copper-iron and copper-zinc antimony sulfide crystal lattice of tetrahedrite. Its name comes from its common crystal form, tetrahedrons.

If you did not enjoy this romp through etymology and mineral nomenclature, well, there won’t be a quiz. Just be glad the guy's name wasn't Johan Jacob Bindleheimer Schmidt.* No telling where that might have led me.

*For the uninitiated, John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt is a traditional children’s song that may have originated in vaudeville acts popular in immigrant communities in the U.S.

The IMA has a lot to answer for. They periodically change the rules. Then change them back. Then change them again, etc. If bindheimite is in fact, a valid species, then (in my limited understanding), the name maybe should have stayed put. The approach to naming oxyplumboanythingite, and any other groups where these types of "rules" apply, sometimes leaves pre-existing names, and only uses the new nomenclature for newly described minerals. Except when it doesn't! And then of course, the earliest name should apply (again, sometimes!) where there are more than one, so it could (should?) be bleinierite?

Love the history and language lessons woven into your posts!