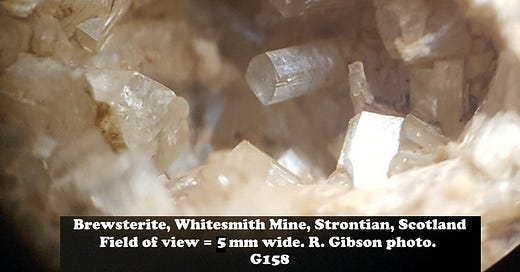

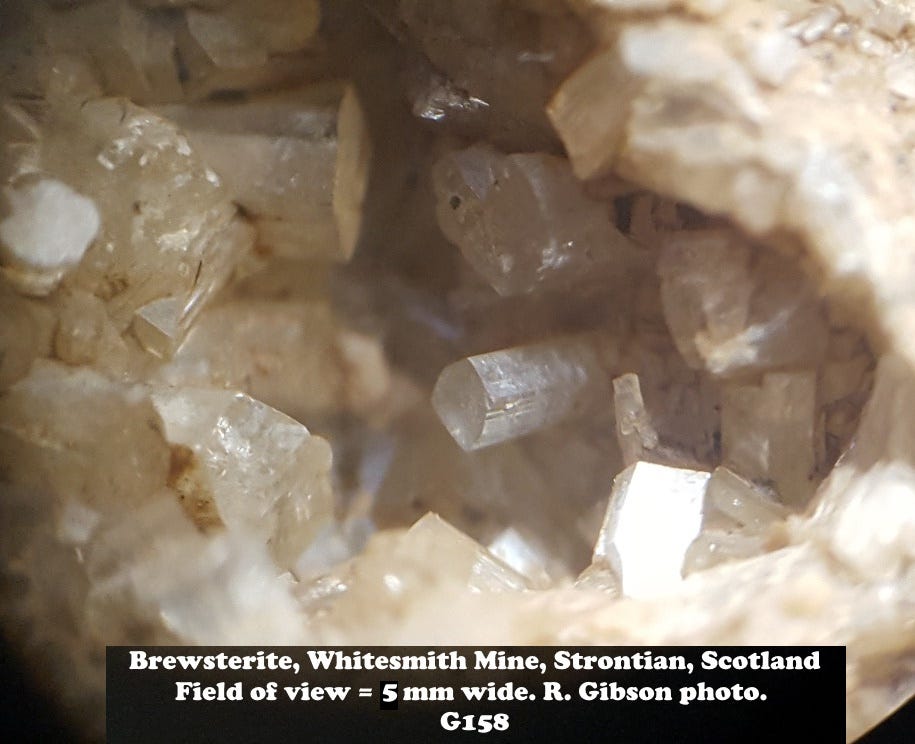

Brewsterite-Sr, (Sr,Ba,Ca) [Al2Si6O16] · 5H2O, is the strontium-dominant end member of a series with barium. The brewsterite group minerals are zeolites, fundamentally aluminosilicates. My specimen is from the Whitesmith Mine at Strontian, Scotland, and Strontian is the type locality for both brewsterite-Sr and strontianite, strontium carbonate. And it won’t be a surprise that the element strontium takes its name from this location as well.

The village of Strontian’s name derives from Gaelic Sròn an t-Sìthein, which means the nose or point of the fairy hill, a reference to a hill or burial mound associated with the mythological sídhe, supernatural folk commonly equated with fairies or elves, but extended to fallen angels, “good folk,” and many others. The Irish banshee, from Old Irish “ban síde,” meaning "woman of the sídhe," and Star Wars’ Sith (from the Scottish spelling of sídhe) are among many connections in Celtic mythology.

Lead mines at Strontian began to operate in 1722. In 1790 and 1793, respectively, Adair Crawford (a doctor) and chemist Thomas Hope recognized a likely new element in the ores from Strontian (the brewsterite and strontianite, although only strontianite had been formally described, in 1791). The element was isolated in 1808 by Humphrey Davy, who named the new element strontium, the only element named for a place in the United Kingdom. Lead from Strontian was important in making British bullets for the Napoleonic Wars.

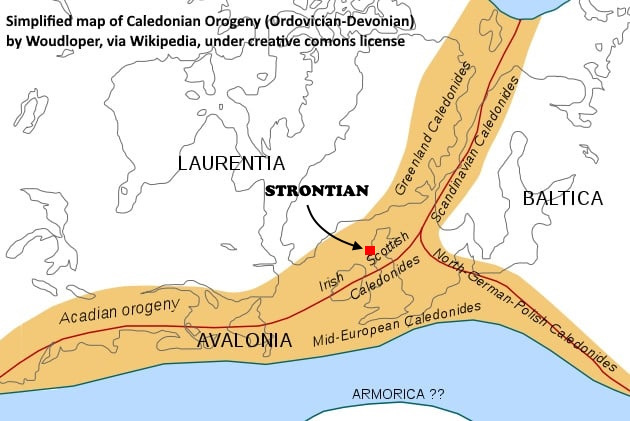

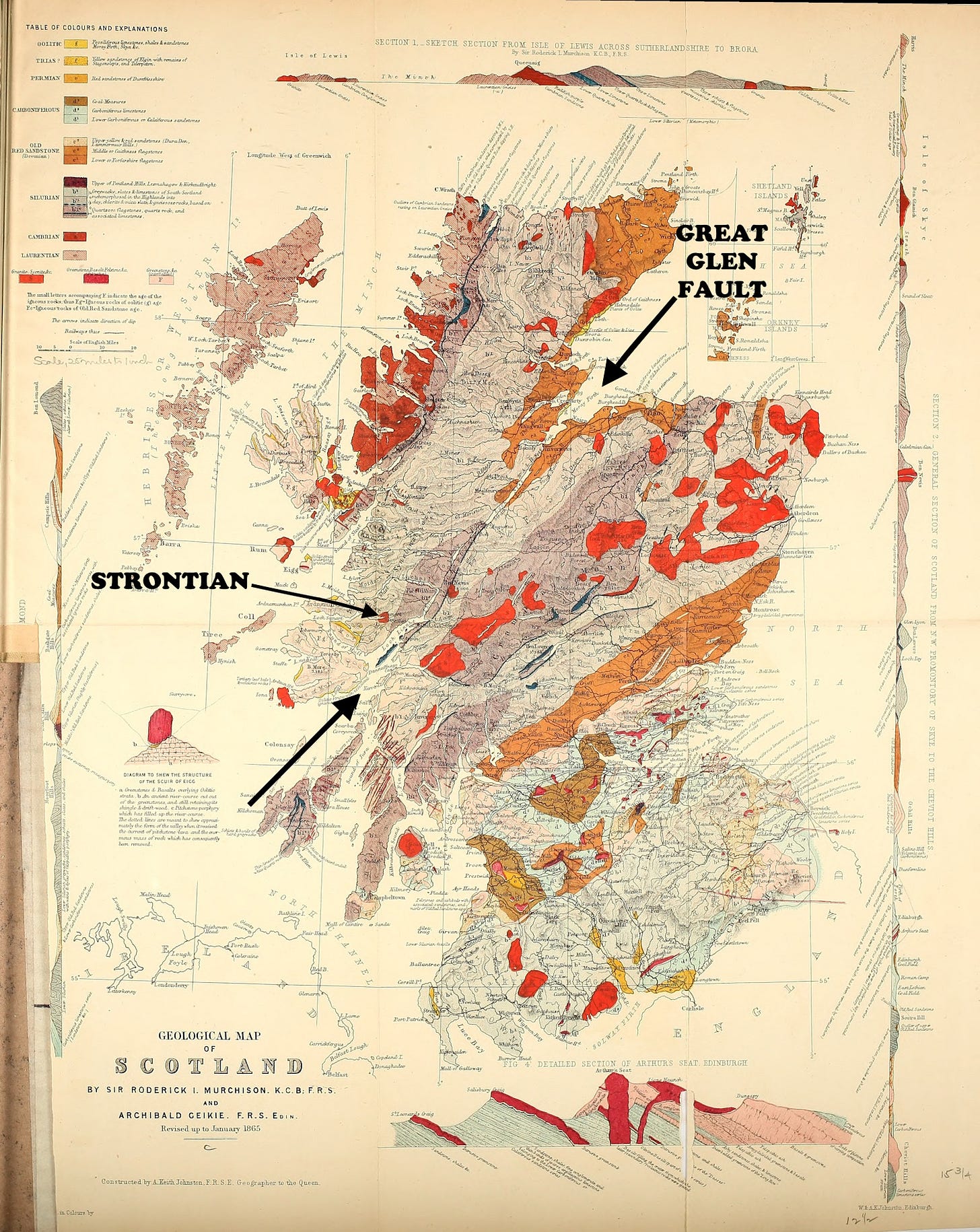

The lead ores at Strontian are associated with granites that were intruded during the Caledonian Orogeny (“orogeny” = “mountain birth”) from Ordovician to Early Devonian time, about 490–390 million years ago, when a major thrust fault (the Moine Thrust) caused movement on the Great Glen Fault, which cuts across Scotland and is evident today as the linear zone where Loch Ness lies.

Strike-slip movement on the Great Glen Fault was expressed as extension in one splay, near Strontian, where the granite intruded (Hutton, 1988, Igneous emplacement in a shear-zone termination: The biotite granite at Strontian, Scotland: GSA Bull. 100:9, p. 1392). The Caledonian Orogeny records the collision between the ancient core of Europe (the Baltic Craton) and North America (Laurentia). It is best expressed in Greenland, Norway, Ireland, and Scotland. The name is from Caledonia, the Roman name for Scotland, from a tribal name, Caledones, probably ultimately from Proto-Celtic roots kal- "hard" and phedo- "foot," 'possessing hard feet', alluding to steadfastness or endurance.

Northern Scotland was part of North America (Laurentia) at the time, amalgamated to Europe (Baltica) by this collision. In North America beyond Greenland, the collision was between the continent and a long narrow continental fragment called Avalonia, and it is called the Acadian Orogeny, recorded best in New England, maritime Canada, and Newfoundland. When the North Atlantic Ocean opened much later (about 80 million years ago), the division did not follow exactly along the old collision zone. So Scotland, which had been part of North America, was “left behind” as an appendage of Europe.

The Whitesmith Mine where my brewsterite specimen is from was named for John Whitesmith, an 18th century miner. Although the little prismatic brewsterite crystals in my photo at the top might appear to be orthorhombic or even tetragonal, brewsterite actually belongs to the monoclinic crystal system. The brewsterite, other zeolites, and other unusual minerals from Strontian, including harmotome (barium silicate, Ba2 (Si12Al4) O32 · 12H2O), ancylite (strontium-cerium carbonate), and kainosite (a calcium-yttrium silicate-carbonate) are late-stage deposits in the lead-zinc veins.

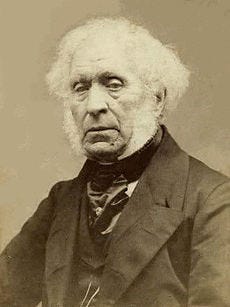

Brewsterite was named by British mineralogist Henry James Brooke in 1822 for Scottish physicist David Brewster (1781-1868), for his “important discoveries connected with crystallography” and his development of optical mineralogy. William Whewell, who coined the word “scientist,” called Brewster the "father of modern experimental optics" and "the Johannes Kepler of optics." Brewsterite was elevated to a series from strontium to barium in 1997 so now there are officially two discrete minerals, brewsterite-Sr and brewsterite-Ba.

David Brewster was a prolific inventor. He devised the complex many-faceted lens that French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel perfected (we know it as the Fresnel lens today) that intensified light to make it ideal for use in lighthouses. His discovery of a way to calculate the angle of incidence of light that would result in the greatest polarization (Brewster’s angle) is used to adjust radio signals and to maximize the magnification in molecular microscopes. And in 1816, Brewster invented the kaleidoscope.

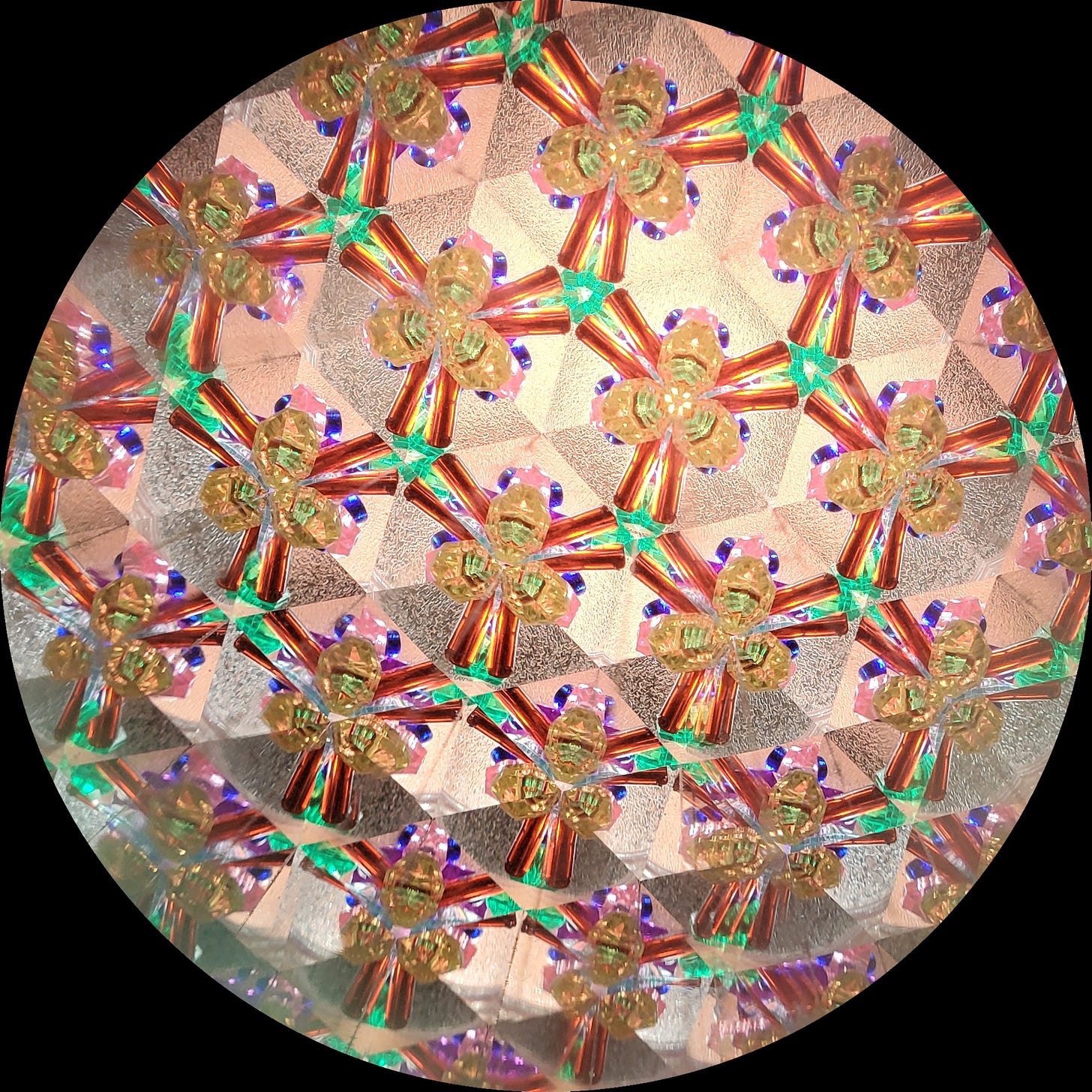

Peter M. Roget, of Thesaurus fame, celebrated Brewster’s kaleidoscope this way: “In the memory of man, no invention, and no work, whether addressed to the imagination or to the understanding, ever produced such an effect.” Brewster’s name for it, the word kaleidoscope, comes from Greek words meaning "observation of beautiful forms." The Brewster Kaleidoscope Society is probably the preeminent organization related to kaleidoscopes today. My kaleidoscope image here is through a little one given to me by my friend Patricia Dickerson.

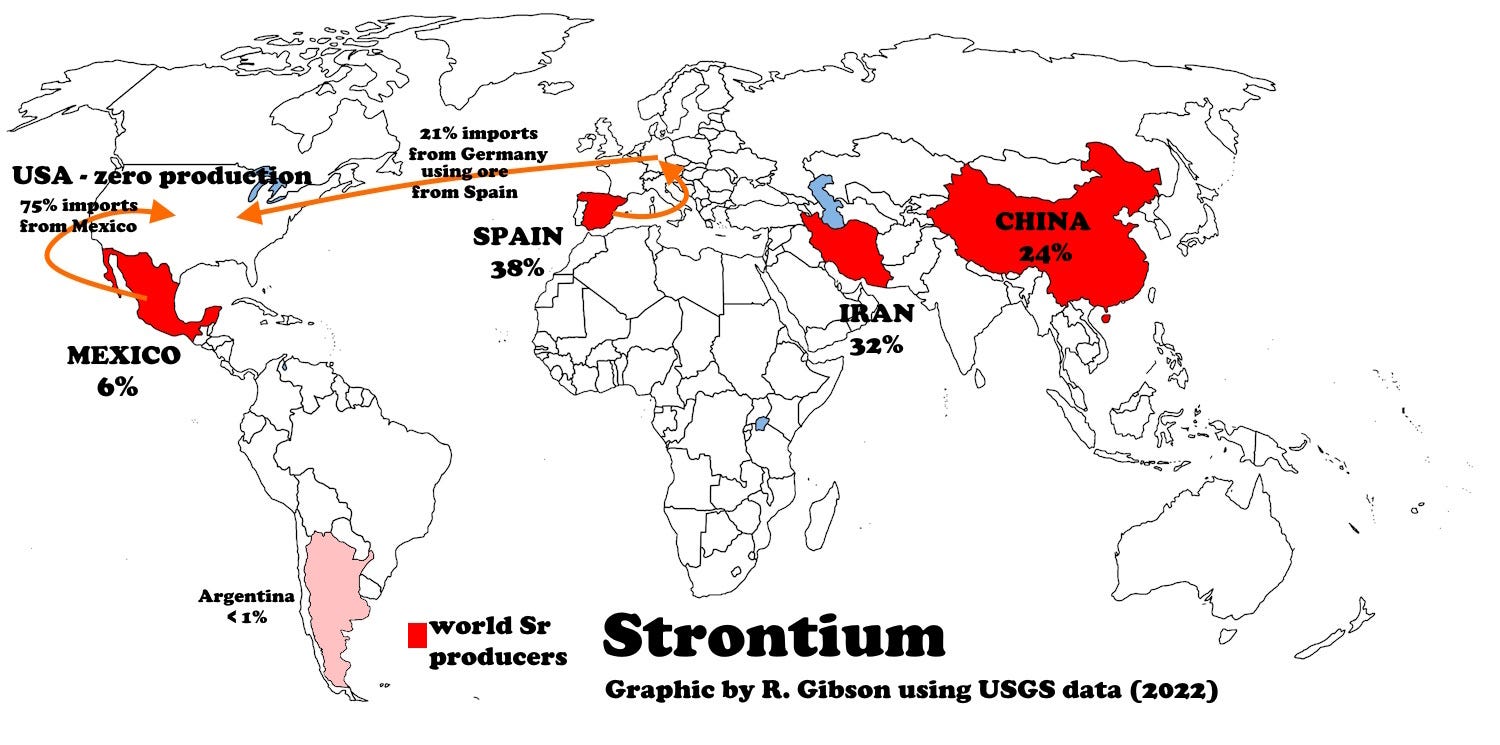

Strontium minerals have not been mined in the United States since 1959, and the US is 100% dependent on imports for the 5,120 tons of strontium we consumed in 2021. That’s a dramatic decrease from 23,000 tons in 2018 and reflects the downturn in oil well drilling due to the low price of oil in that time frame; the largest use of strontium, as the mineral celestite (strontium sulfate, the most common strontium mineral), is in drilling fluids to help control pressures. In a post-Covid rebound and increase in oil prices, strontium consumption in the US more than doubled from 2021 to 2022, to 12,000 tons.

Other important but volumetrically small uses of strontium include the red colors in fireworks and signal flares, applications in specialty ceramic magnets, and in some toothpastes. Strontium isotope ratios are informative for determining the affinities of geological terranes and for tracing the provenance of some archaeological materials, and strontium isotopes are used to help treat some prostate and bone cancers. Strontium helps remove lead impurities in zinc refining. Historically, most strontium was used in glass, especially television CRT faceplates, where it stopped x-ray emissions.

75% of US strontium imports today come from Mexico, but almost all the world’s production comes from four countries: Spain (38% of the total), Iran (32%), China (24%) and Mexico (6%). US imports of strontium compounds from Germany (21% of total imports) are from German processors of mostly Spanish ores.

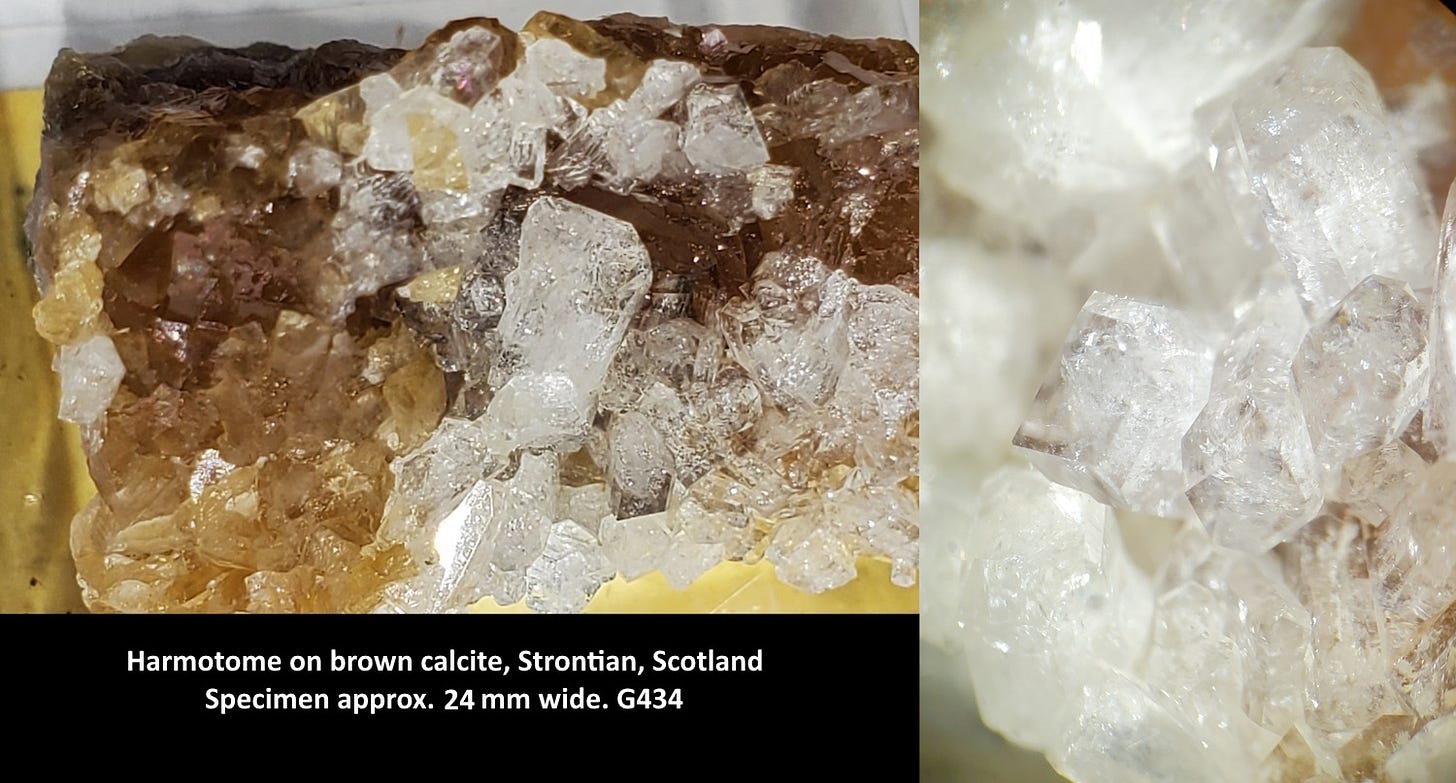

Harmotome is from Greek ἁρμός (armós, “joint, shoulder”) and τομή (tomḗ, “section, cut”), a reference to twin crystals with faces repeated to make cruciform twins shaped much like the well-known staurolite crosses. I don’t see any such twins in my specimen here, which is from Strontian with no additional label information, but most (but not all) harmotome with this distinctive brown calcite is from the Clashgorm Mine.

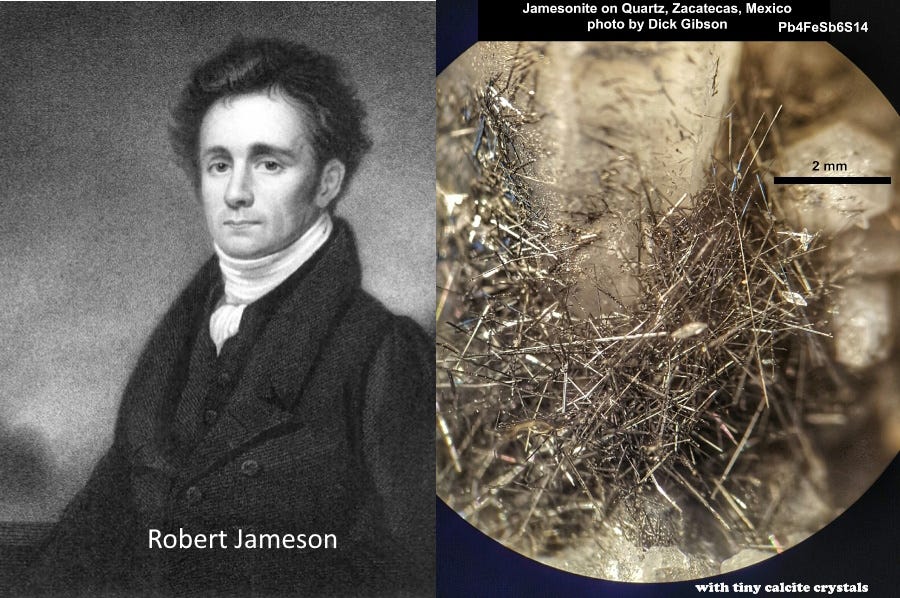

The name harmotome appears to have been given by geologist Robert Jameson in 1804. Jameson (1774-1854) was Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, and is the namesake of the sulfosalt jamesonite.

Another excellent article Richard. I learnt a lot from it.