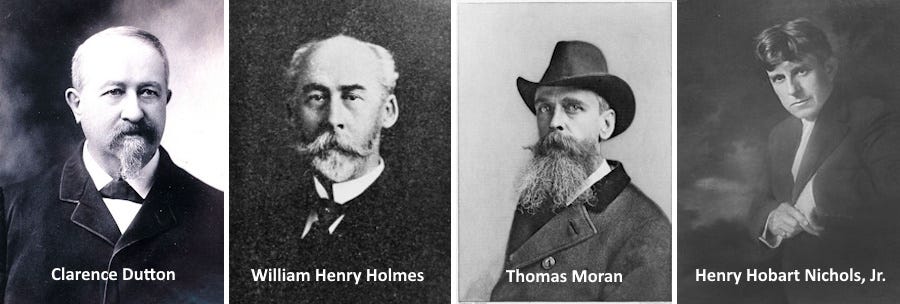

Clarence Dutton and colleagues

A tribute to science and artistry

Life in the USA is not normal. These posts have been scheduled for over a month, and they will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them.

I recently acquired a copy of the US Geological Survey Second Annual Report, for 1880-1881, published in 1882. Although it contains fine papers on pluvial Lake Bonneville (by G.K. Gilbert) and the geology of the Leadville, Colorado (S.F. Emmons) and Washoe, Nevada (G.F. Becker) mining districts, the star of this volume is Clarence E. Dutton’s report on The Physical Geology of the Grand Canyon District.

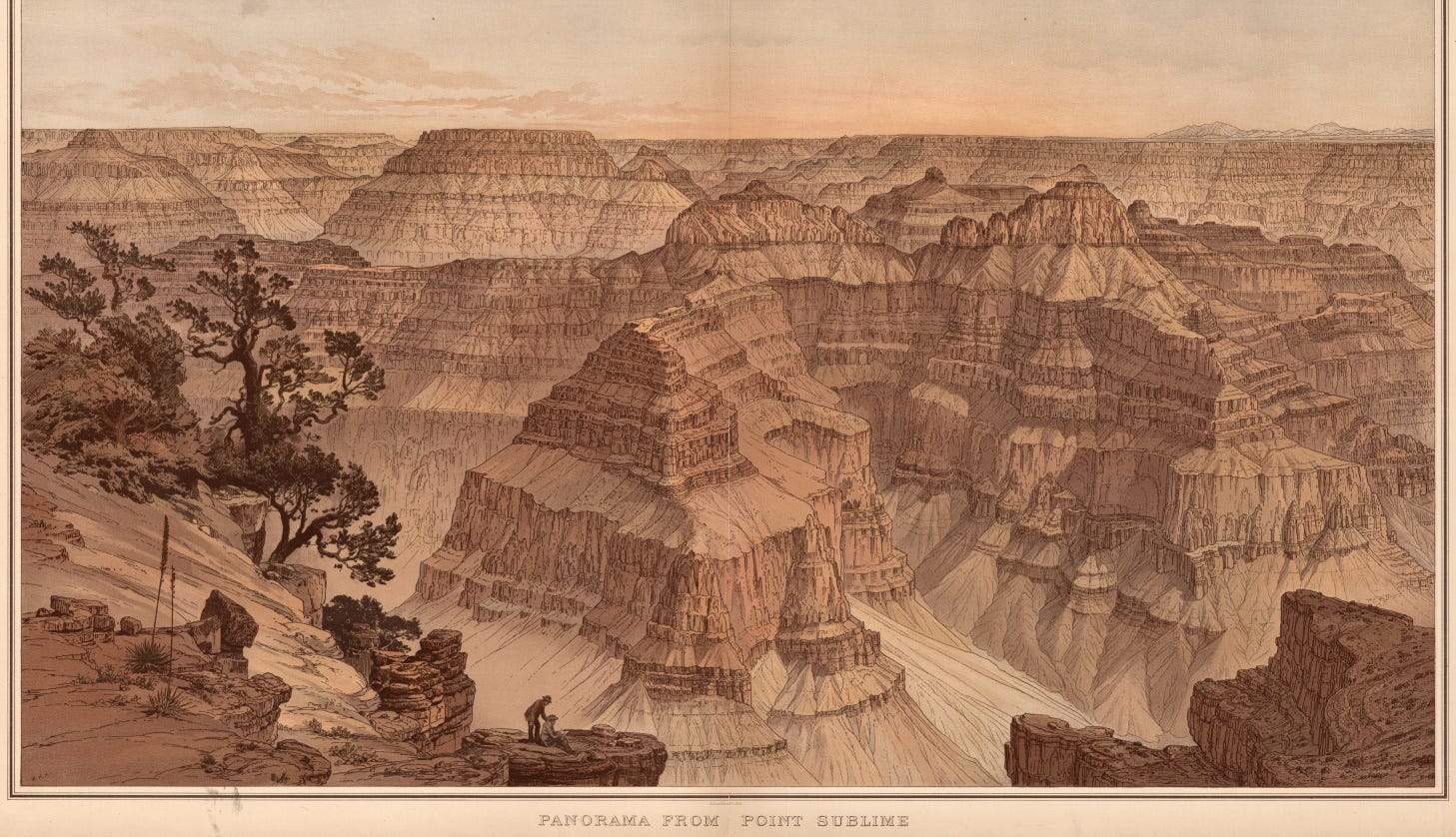

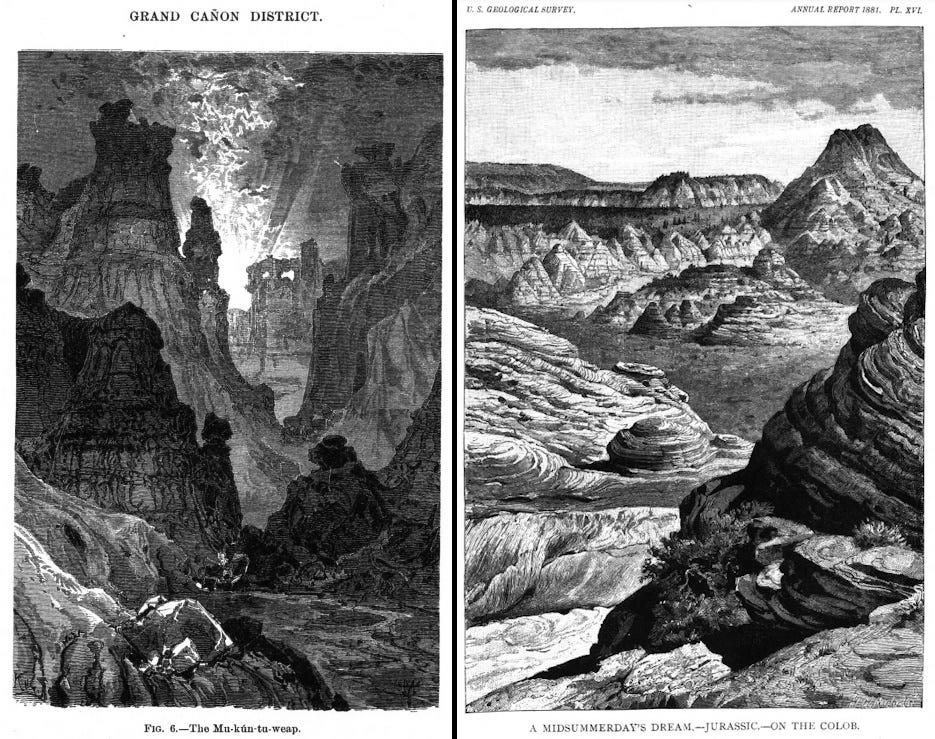

To be clear, this is not Dutton’s magnificent USGS Monograph #2, Tertiary history of the Grand Canyon district, with atlas, which was in progress and published a bit later in 1882 than the Annual Report. Monograph 2 is way beyond my price range; if you can find the Atlas for less than $10,000 in decent condition, you should go for it. The Second Annual Report does contain many more illustrations than the text of the Monograph, including the line drawings by William Henry Holmes (1846-1933) that were engraved and tinted to make the huge fold-out panoramas in the Atlas. One of those, Point Sublime on the North Rim, from my copy, is shown at the top of this post, and the same illustration from the Atlas is below, from a digitized version of the Atlas online.

Holmes was a geologist and archaeologist as well as an artist. John Wesley Powell, at the time the newly appointed Director of the Geological Survey, wrote of him and his illustrations of the Grand Canyon, “Only the artist and geologist combined could have graphically presented the subject in a manner so instructive and beautiful.”

The report also has fine illustrations by renowned artists Thomas Moran (1837-1926) and Henry Hobart Nichols. Therein lies a small conundrum: Henry Hobart Nichols, Jr. (1869-1962) started his 15-year career as an artist with the USGS by most accounts in 1889, when he was 20. If his birth year (1869) and the publication date of the Second Annual Report (1882) are to be believed (as they must), he was only 13 when his illustrations in this volume were drawn, and this seems unreasonable. However, his father, Henry Hobart Nichols, Sr., was a noted wood engraver in Washington, D.C., who engraved the sketches in The History of North American Birds by Baird, Brewer and Ridgeway, and the Nichols drawings in the Dutton report appear to be wood engravings. So even though I find no reference to Nichols Sr. working with the USGS, I suspect that he is the artist for the Dutton paper in the Annual Report, even though the son is more well known as a USGS artist. Whichever H.H. Nichols it is, he is uncredited except in his name on the engravings.

Clarence Dutton was a prolific geologist with the USGS, working on projects as diverse at the Charleston earthquake of 1886 and the volcanism at Kilauea in Hawaii (1884). His team determined the depth of Crater Lake as 1,996 feet (608 m) in 1886, remarkably close to the modern accepted value of 1,943 feet (592 m). Dutton coined the term isostasy in 1882 “to express that condition of the terrestrial surface which would follow from the flotation of the crust upon a liquid or highly plastic substratum – different portions of the crust being of unequal density.” Isostasy is a concept vital to modern plate tectonics, derived from Greek words for equal and station.

Dutton’s writing would be considered florid by many modern readers, but as one of the first scientific reporters on the Grand Canyon, he can perhaps be forgiven. His exuberance at the scenes he saw is unbridled.

At length the sun sinks and the colors cease to burn. The abyss lapses back into repose. But its glory mounts upward and diffuses itself into the sky above. Long streamers of rosy light, rayed out from the west, cross the firmament and converge again in the east ending in a pale rosy arch followed by the darkening pall of gray, and as it ascends it fades and disappears, leaving no color except the after-glow of the western clouds, and the lusterless red of the chasm below. Within the abyss the darkness gathers. Gradually the shades deepen and ascend, hiding the opposite wall and enveloping the great temples. For a few moments the summits of these majestic piles seem to float upon a sea of blackness, then vanish in the darkness, and, wrapped in the impenetrable mantle of the night, they await the glory of the coming dawn.

— Clarence Dutton, The Chasm in the Kaibab

My copy of the Second Annual Report was withdrawn from the University of Idaho library which received it in 1968, and I obtained it from a second-hand bookstore in Butte, Montana. But it began its life as a Congressional presentation copy, inscribed and signed with “Compliments Hon. Wm. Aldrich.” Aldrich was a three-term congressman from Illinois from 1877 to 1883, and he probably presented this copy of the book when it was new to the Union League Club of Chicago, whose name is hand stamped on the title page. Aldrich died in 1885 at age 65; his son, James Franklin, also served in the U.S. House of Representatives. The Union League started in 1862 as an anti-slavery, pro-Union organization. Chicago’s Union League Club began in 1879 and continues as a civic and community organization today.

If you are interested in more from me about the rocks in the canyon, please visit this podcast episode. And if you missed it, here’s my previous compilation of posts on the History of Geology.

Thank you for sharing these beautiful illustrations. Didn't know such artistry was a thing. Thank you too for using "normality" as an act of resistance.