Cottonwood Canyon, on the north side of Interstate 90 east of Cardwell, Montana, USA, transects a near-vertical section of the Precambrian Belt Grayson Shale and the Cambrian Flathead, Wolsey (with a prominent Silver Hill member), Meagher, Park, and Pilgrim Formations.

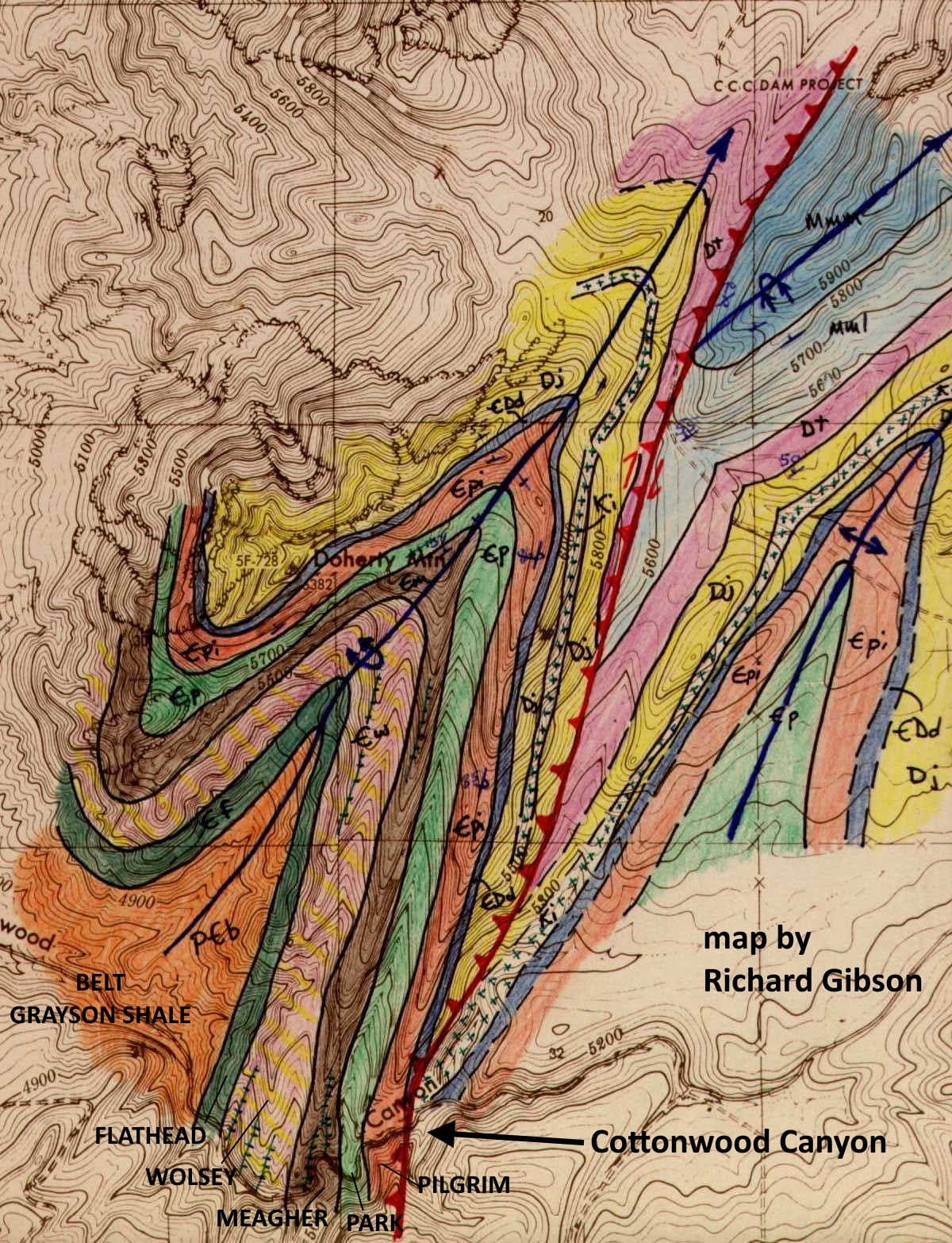

The rocks are nearly vertical because they have been folded by thrust faulting, part of the Sevier Orogeny that pushed these rocks eastward about 75 to 60 million years ago. The section is in the eastern, steep limb of the Mt. Doherty anticline (shown in my map above), and as you continue north along the strike of the formations, they become overturned, with the older layers above the younger strata. The associated syncline is to the east, but it is cut by a fault that broke through the steeply inclined strata between the anticline and syncline (largely in the weak Devonian Three Forks Shale and/or in sills, which are also typically mechanically weaker than carbonates like limestone and dolomite). Although it does not have a great deal of offset, it is an easily mappable fault. It has no observable expression other than the disruption of the sequence of rocks. That’s typical of faults, which are only rarely actually visible directly. Faults are typically inferred, but in a situation like this, that inference is absolutely certain even though the fault is not literally visible and as far as I know has no modern seismic activity on it.

All the formations in Cottonwood Canyon are intruded by diverse andesitic sills. Andesite is an igneous (formerly molten) rock intermediate in composition between basalt and rhyolite, and a sill is an igneous intrusion that is parallel to, injected between, the layers of a sedimentary rock. In contrast to a sill, a dike is a similar intrusion that cuts ACROSS the bedding layers of the sedimentary rocks.

But sills and dikes are not completely mutually exclusive.

Although the andesite bodies in my photo at top (with Joel Dietrich for scale) are overall pretty much parallel to the bedding in the Flathead through Pilgrim Formations, in places, they cut across the bedding, making local dike-like features. The annotated photo shows the contacts between the dark andesite intrusions and the gray limestone of the Cambrian Meagher Formation. The Meagher was deposited about 510,000,000 years ago, but the tilting and intrusion of the sills occurred much more recently, around 77,000,000 million years ago, about the same time as the Boulder Batholith around Butte (age dating of the sills by Harlan, Geissman, Whisner, and Schmidt, 2005, Earthscope in the Northern Rockies Workshop).

In places, the discordant dike-like nature of these intrusions makes them completely surround some blocks of the country rock, the Meagher limestone, at least in the cross section displayed in Cottonwood Canyon. Whether that surrounding continues into the rock, in the third dimension, is not apparent, but it is likely that they do to some extent. One block is present (not in my photo) that is metamorphosed to marble and is probably essentially a xenolith (“strange rock”), an inclusion within the formerly molten andesite where it got cooked a lot more than the main mass of the limestone.

Which came first, the tilting or the intrusion? Although I don’t have a photo of it, some of the now-vertical sills contain rows of little oval cavities, elongated parallel to the contact between the andesite and limestone and concentrated on the eastern sides of the sills. East is stratigraphic up, meaning that as you walk through Cottonwood Canyon the vertical rocks get younger as you go east. They were all originally laid down horizontally, but the Sevier Orogeny’s compression tilted them. But because we know the sequence of older-to-younger, we know which way used to be up when the rocks were horizontal.

Those cavities in the andesite represent gas bubbles in the formerly molten material that rose to the top of the igneous body before it solidified, so that tells us that the eastern sides of the sills were once the tops of the sills, toward which the gas bubbles rose buoyantly in the molten material. That in turn tells us that the sedimentary rocks were still lying horizontally when the sills were intruded, and the whole package was later tilted to near vertical.

In places, the sills have chilled margins, where they were quenched against the old, cold sedimentary rocks they intruded. They also contain partially assimilated pyroxene crystals, and at least one is really two intrusions (or possibly the same one that differentiated a bit before it solidified), one within the other. In the second photo showing a sill in the Meagher, the holes you see in the lower part of the sill represent samples taken for paleomagnetic studies that measured the orientations of iron minerals in the rock to determine ancient magnetic pole positions that may have been dramatically different from today. Paleomagnetic work by Harlan and others also indicates that the orientations are consistent with injection of the sills before the rocks were titled.

This canyon is a spectacular classroom for both Cambrian stratigraphy and for the nature of igneous intrusions, in this case of Cretaceous age.

The Mt. Doherty structures are within the Helena Salient of the Montana fold-thrust belt. The rocks here have been transported from the west by multiple levels of thrust faults pushing east. How far? Uncertain, but the Cambrian strata generally thicken to the west, and the Mt. Doherty rocks are in part thicker than their untransported counterparts in place in the northern Tobacco Root Mountains (even when taking into account the thickening created by the sill intrusions). It’s reasonable to suppose that the rocks in Mt. Doherty were moved at least 5 to 10 kilometers from their originally location in the west, and that distance of transport might be as much as 20 km or more (see Schmidt, Whisner, and Whisner, 2018, Road Log to the structural geology of the Lewis and Clark State Park and surrounding area, Southwestern Montana: Some new ideas and more questions: Northwest Geology, The Journal of the Tobacco Root Geological Society, v. 47, p. 41-68).

There isn’t much in the way of minerals in these rocks; in most places, the carbonates are barely mineralized or metamorphosed to marble at all, even in the contact zones of the intrusions. But here’s a photo of a quartz-lined vug in the Devonian Jefferson Dolomite, from just up-section from these rocks in Cottonwood Canyon — a normal sedimentary diagenetic feature, not a result of contact metamorphism.

Cottonwood Canyon is a public road, with mostly state or BLM land adjacent, but some private land is nearby; please do not trespass. The road was readily accessible on April 24, 2021, and typically remains so later in the summer, but be aware that in wet spring seasons (May-June) or after thunderstorms, the road can be treacherous with sloppy mud and there is one grade that can be almost impassable for even 4-wheel-drive vehicles when it is really wet.

Cannot resist offering this link to a photo of a statue of Thomas Francis Meagher in his role as Union General in charge of the New York Irish Brigade, name sake of Meagher County for which the Meagher Formation is named. Hope you don't find this too unwieldy https://images.search.yahoo.com/yhs/view;_ylt=AwrijXeV.45mKJwkkEo2nIlQ;_ylu=c2VjA3NyBHNsawNpbWcEb2lkAzZmYjhmNzkyZTEwMGYxNzY4MDIyMzBkNzk0MmRjZjk1BGdwb3MDNARpdANiaW5n?back=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.search.yahoo.com%2Fyhs%2Fsearch%3Fp%3DMeagher%2Bstatue%26ei%3DUTF-8%26type%3Dud-c-us--s-p-cvtyqrye--exp-none--subid-none%26fr%3Dyhs-infospace-047%26hsimp%3Dyhs-047%26hspart%3Dinfospace%26param1%3Dzmffime51eteka034eyyn87j%26tab%3Dorganic%26ri%3D4&w=1300&h=955&imgurl=c8.alamy.com%2Fcomp%2FCW10PE%2Fthomas-francis-meagher-statue-montana-state-capitol-building-helena-CW10PE.jpg&rurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.alamy.com%2Fstock-photo-thomas-francis-meagher-statue-montana-state-capitol-building-helena-49809718.html&size=218.4KB&p=Meagher+statue&oid=6fb8f792e100f176802230d7942dcf95&fr2=&fr=yhs-infospace-047&tt=Thomas+Francis+Meagher+Statue+Montana+State+Capitol+Building+Helena+MT+...&b=0&ni=90&no=4&ts=&tab=organic&sigr=U.rrHLNnbasN&sigb=vGK_KOzIkIMm&sigi=LIjXVz75Zr33&sigt=NAtTdtBjxdSN&.crumb=wUk13GGL5Rx&fr=yhs-infospace-047&hsimp=yhs-047&hspart=infospace&type=ud-c-us--s-p-cvtyqrye--exp-none--subid-none¶m1=zmffime51eteka034eyyn87j

In UK items like the gas bubble holes are called "way up structures" which is charmingly direct. Arthur's Seat Edinburgh is a similar classroom in igneous intrusions, where Charles Darwin was taught some wrong "Neptunian" geology (the dolerite was supposedly crystallised out of some primordial ocean. When it rather clearly wasn't)