I count it as part of my job to de-jargonize geology, because jargon obfuscates meaning and limits access to the wonderful world of the earth. But it’s also true that we use jargon because it’s a lot easier to say “granodiorite” than “a coarse-grained plutonic igneous rock with 20 to 60% quartz and with 65-90% plagioclase vs. alkali feldspar and containing some mica and other minerals.”

Diabase is a rock with the same composition as basalt or gabbro (lots of calcium plagioclase feldspar and dark iron-rich minerals like amphiboles and pyroxenes), but which is intermediate in texture (grain size) between fine-grained basalt and coarse-grained gabbro. It often means the rock crystallized underground, but at a relatively shallow depth compared to basalt (on or really near the surface, where the magma crystallizes quickly, making tiny crystals) and gabbro (deep, where it takes longer to cool, and the mineral crystals can grow larger). Usually the crystals in diabase are small but visible.

That relatively shallow depth of formation means that diabase often occurs in dikes and sills. Dikes are cross-cutting igneous intrusions and sills are concordant (parallel to things like bedding in the country rock) igneous intrusions, both often, but by no means always, at those shallow depths.

To confuse things further, sometimes different words are used for the same thing. Dolerite is the word used for this rock in Britain and much of the English-speaking world outside North America. And in a further twist, some geologists who use dolerite use diabase to mean altered dolerites or basalts. I’m sorry for this crazy-making confusion. Why does it exist? No good reason that I know of, just the way usage evolved.

Diabase was first used by French mineralogist Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847) in 1807 for rocks composed mostly of feldspar and amphiboles, two minerals forming the bases of the rock, from Greek διάβασις (diábasis, two bases). Alternatively, he might have taken the Greek meaning in the sense of “crossing over, transitioning,” because of the frequent occurrence of the material in cross-cutting dikes.

At about the same time, another prominent French geologist, René Just Haüy, used the name diorite for the same kinds of rocks. Diorite is from Greek words meaning distinguish or separate, for the distinct white feldspar and dark amphibole in the rocks. Brongniart eventually agreed that diorite was the right word and himself abandoned use of diabase in 1827. It should have ended there, and everyone would call these rocks diorite today.

But in 1877 influential German geologist Harry Rosenbusch argued that there was an age aspect to these rocks, and that diabase was older (pre-Cenozoic, more than 65 million years old) and diorite was younger. This age criterion got conflated with the use of dolerite in Britain, leading to the idea that diabase referred to altered (older) dolerite. Age is no longer a factor in these names, but the suggestion of diabase as altered dolerite is still sometimes used, even though most petrologists would probably consider dolerite and diabase to be full synonyms.

The word dolerite is from Greek doleros, “deceitful, deceptive,” because it was easily confused with diorite. No wonder since the original definitions were almost the same.

But wait, you say, I threw in a new word there: diorite. Shouldn’t that be yet another synonym, since Brongniart and Haüy meant the same thing with those words? Well, it didn’t quite work out that way. Diorite has come to mean a rock that’s somewhat more coarse-grained than diabase or dolerite, and maybe a slightly higher silica content. Diorite has a “legal” definition among petrologists, with a specific chemistry, but you can’t tell the composition a plagioclase feldspar in the field, so terms like “diabase dikes” and subjective, qualitative names like diorite (unanalyzed) still get frequent use.

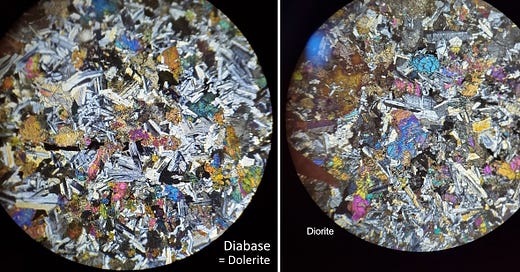

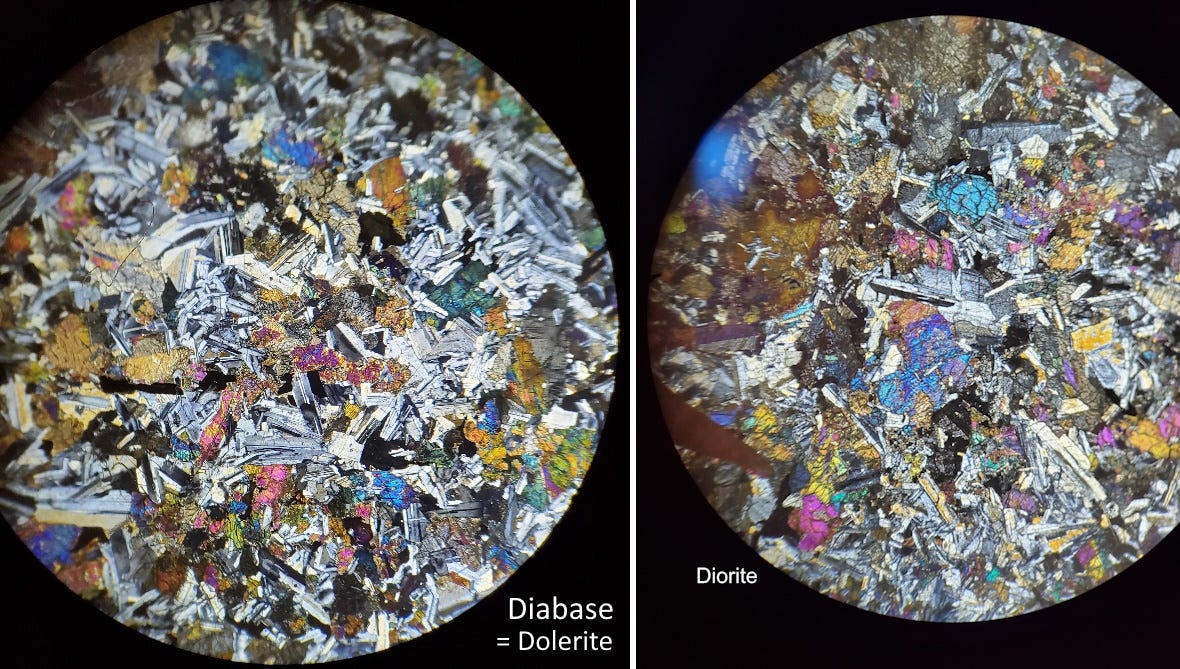

The thin sections at the top were labeled diabase and diorite. It’s pretty challenging to see much visible difference between them.

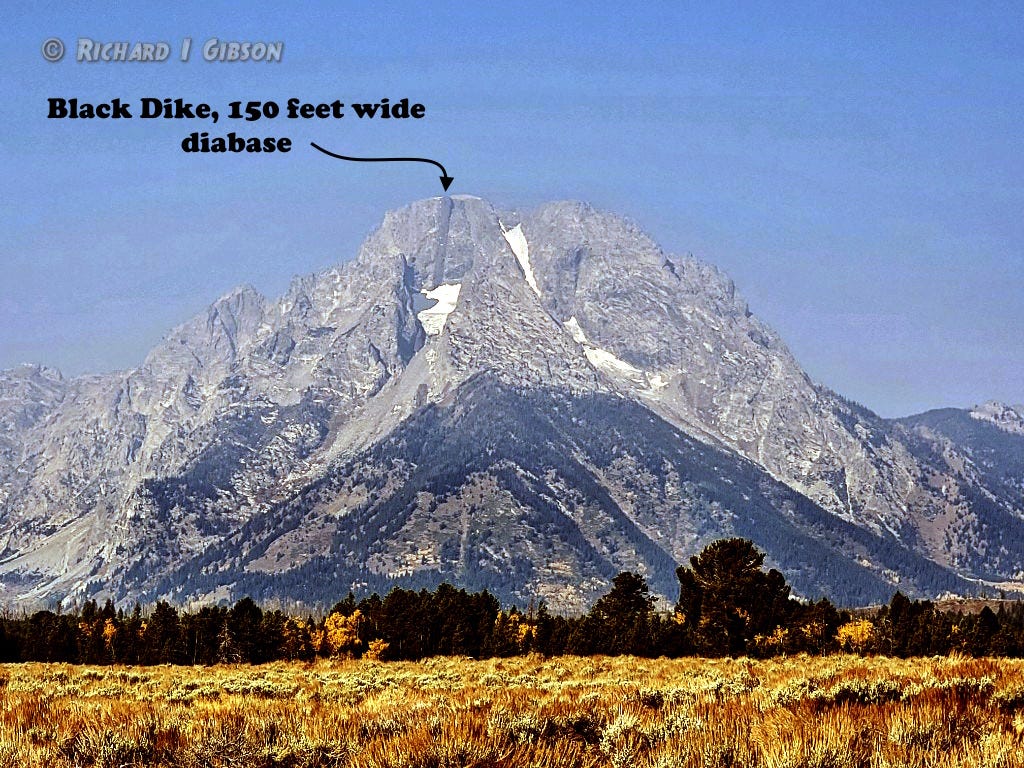

To try to escape this tedious jargon, here are photos of some of the most famous diabase dikes in the United States.

The Black Dike on Mt. Moran in the Grand Tetons and the much narrower dike on Middle Teton are both diabase dikes dating to about 780 million years ago.

780 million years ago is a poorly understood time in earth history. The older rocks of the Tetons, the gray-white granite gneiss in my photo, are very old, 2.5 to 2.8 billion years, and are part of the Wyoming Craton, one of the early-formed continental blocks that form the cores of continents. But there just aren’t many rocks preserved in the time from say 900 to 600 million years ago. One reason for this may be Snowball Earth, a long period of glaciation when virtually the entire planet was covered with ice (although the best-documented Snowball Earth is later, around 650 million years ago); another reason may be that many of the continental masses were relatively stable, neither colliding nor breaking apart much, to create uplifts to erode and basins into which sediment could be shed (and preserved).

Dikes like these are found scattered through western North America from Wyoming north to the Yukon and Great Slave Lake. The activity about 780 million years ago has been called the Gunbarrel Mafic Magmatic Event (Harlan and others, 2003, Geology 31:12), and it might be related to some aspect of the break-up of the supercontinent Rodinia, which had been assembled about 300 million years earlier during the Grenville Orogeny and related collisions.

The famous bluestones at Stonehenge are also dolerite (Bevins and others, 2021, Alteration fabrics and mineralogy as provenance indicators; the Stonehenge bluestone dolerites and their enigmatic “spots”: J. Archaeol. Science: Reports, V. 36, 102826).