In late November, we’ll be coming up on a year of The Geologic Column – 156 posts. THANKS, to everyone who reads and subscribes! I very much appreciate it. And I really appreciate those who have pledged toward a time when I might add paid subscriptions, as well as the direct donations. That tangible support is very gratifying, and I’m glad you find the writing and images interesting and a useful educational resource.

Because of the pledges and donations, I was tempted to turn on paid subscriptions – I like money as much as the next guy. But I truly feel that the kind of science I try to share should be freely available, so I’ve made the decision to not go that route. I’ll be turning off the “pledge” option, with sincere thanks to those who made pledges, for their confidence and explicit support.

These things do take time and effort, so I’ll leave the “Donate once” buttons on posts as a “tip jar” (I do like money as much as the next guy!), and if you are so inclined of course I’ll appreciate anything anyone chooses to do there in support of these posts, but please view it as completely optional: I won’t be taking attendance or checking up on you. And if you have friends who might be interested, using the “share” button is another way of showing appreciation and making me feel good and motivated.

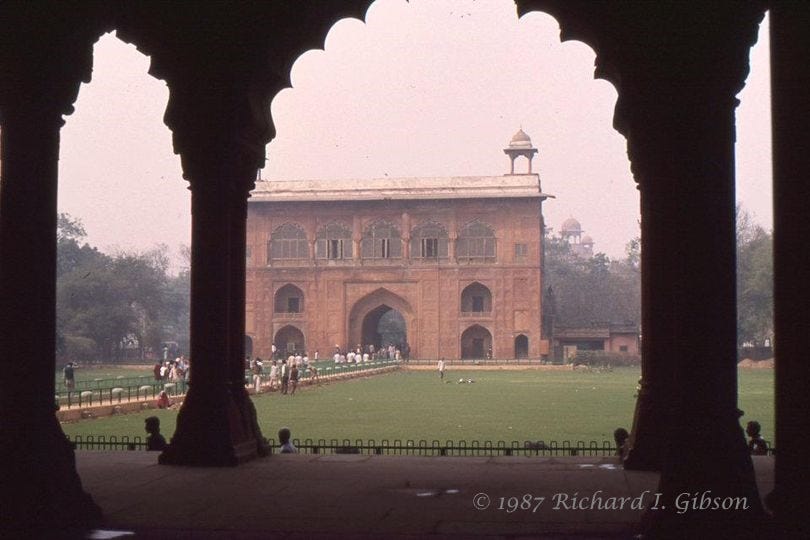

The Red Fort in Delhi, India, was constructed between 1639 and 1648 after Shah Jahan, fifth and arguably most influential of the Mughal emperors, decided to move his capital from Agra to Delhi. Jahan also commissioned the Taj Mahal in Agra as a tomb for his favorite wife, using mostly white marble, although there are accents and associated buildings that use the same red sandstone as the Red Fort.

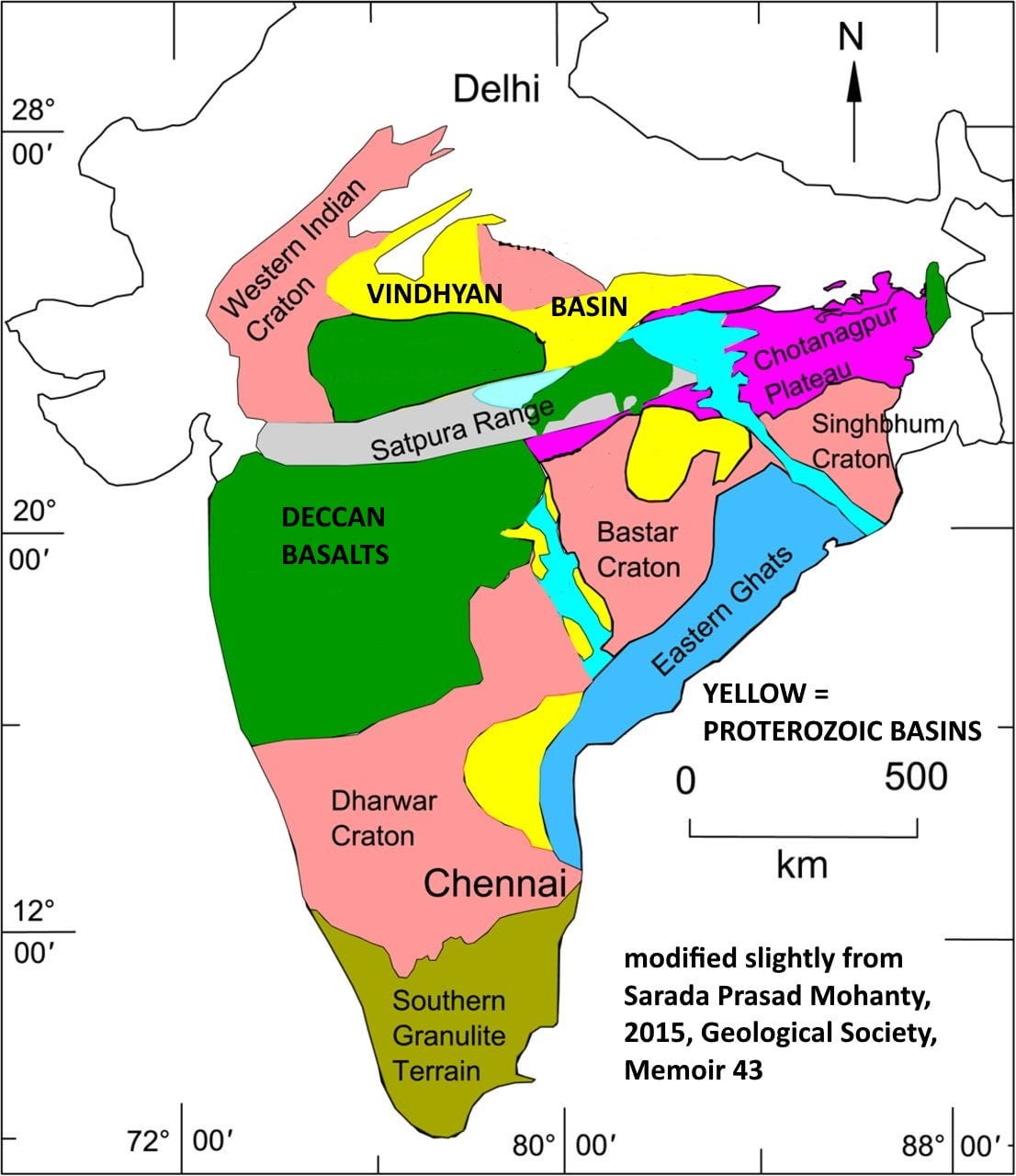

The red and pink rock in the Red Fort and many other monumental structures in northern India comes from the Maihar sandstone, part of the Bhander group which in turn is near the top of the Vindhyan Supergroup of rocks. The Vindhyan is a really thick (around 5,000 meters) package of mostly sandstones, siltstones, and some carbonates that was deposited in a long-lived basin (the Vindhyan Basin) during Proterozoic time. The basin is larger than the state of Montana.

The age of the Vindhyan rocks is controversial, but their deposition appears to have begun at least 1,600 million years ago (maybe as long ago as 1,730 million) and continued for nearly a billion years, at least until about 725 million years ago and maybe as recently as 600 million years ago.

The tectonic setting for the basin is also unclear, with one camp interpreting it as an extensional continental rift basin set into the Archaean rocks of the Indian Shield, and another inferring it to be a foreland basin, the result of the crust being squeezed between two colliding cratonic blocks. In a recent overview, Basu & Chakrabarti (2020, Origin and Evolution of the Vindhyan Basin: A Geochemical Perspective: Proc. Indian Natl. Acad. Sci. 86:1, p. 111) support the latter contention.

Many of the layers in the Vindhyan Supergroup are similar to those of the partly coeval Belt Supergroup in western Montana and adjacent areas: stromatolitic carbonates and iron-rich argillites and shallow water sandstones. The younger red Maihar sandstone was used in the construction of “the Sanchi Stupas, Qutub Minar, Humayun’s Tomb, Tomb of Safdarjung, Agra Fort, Red Fort, Chittorgarh Fort, Buland Darwaza gate in Fatehpur Sikri, and Jama Masjid” (Kaur and others, 2019, Vindhyan Sandstone: A Crowning Glory of Architectonic Heritage from India: Geoheritage 11:6). It is a uniform, relatively fine grained, easily worked stone, known in the trade as Agra Red, Dholpur Red and Beige, and Bansi Pink, among others. Dholpur, just south of Agra, is one of the more important sandstone quarrying areas of India.

The red Maihar sandstone is near the top of the Vindhyan Supergroup, putting it among the youngest strata, probably 650 to 750 million years old. It’s a quartz sandstone, colored various shades of red by hematite (iron oxide) cement. Iron is by far the most significant coloring agent in rocks.

The Maihar was probably deposited in a tidally-dominated estuarine shallow water setting, at a time when algal mats (and perhaps some of the enigmatic Ediacaran fauna) were the dominant life forms in the oceans, and there was no life on land. Some sedimentary features suggest that the area saw periodic storms (Bhattacharyya and others, 1980, Storm deposits in the Late Proterozoic Lower Bhander Sandstone of the Vindhyan Supergroup around Maihar, Satna District, Madhya Pradesh, India: J. Sed. Research 50 (4): 1327–1335).

Shah Jahan had plenty of funds to construct the Red Fort, Taj Mahal, and many other structures. Among other things, he owned the Koh-i-Noor diamond (105.6 carats and in the British Crown Jewels today), estimated to be equivalent in value to about 23% of the world GDP at the time.

The name Vindhyan is from the Vindhya mountain range, whose name was probably derived from Sanskrit “vaindh,” to obstruct, for the barrier-like nature of the range.

The photos are from February 1987 when I was in India to teach a short course on gravity and magnetics in oil exploration to the Oil & Natural Gas Corporation, India’s national oil company, in Dehra Dun.

"stromatolitic carbonates and iron-rich argillites and shallow water sandstone" - so this would record our atmosphere being transformed into an oxygen rich one I guess... In NW Scotland we have the billion year old Torridonian sandstone making some spectacular mountains in Wester Ross.

Really excellent blend of history and geology! Enigmatic Ediacaran life forms is an apt phrase. An evolutionary road not travelled but extraordinary. India's geology is fascinating! You could devote periodic essays on different countries' geologies and I wouldn't complain!