Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

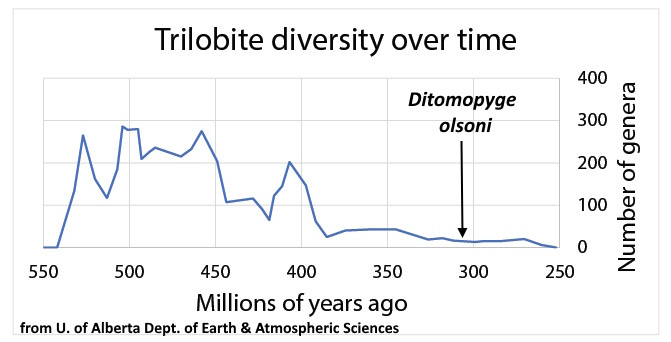

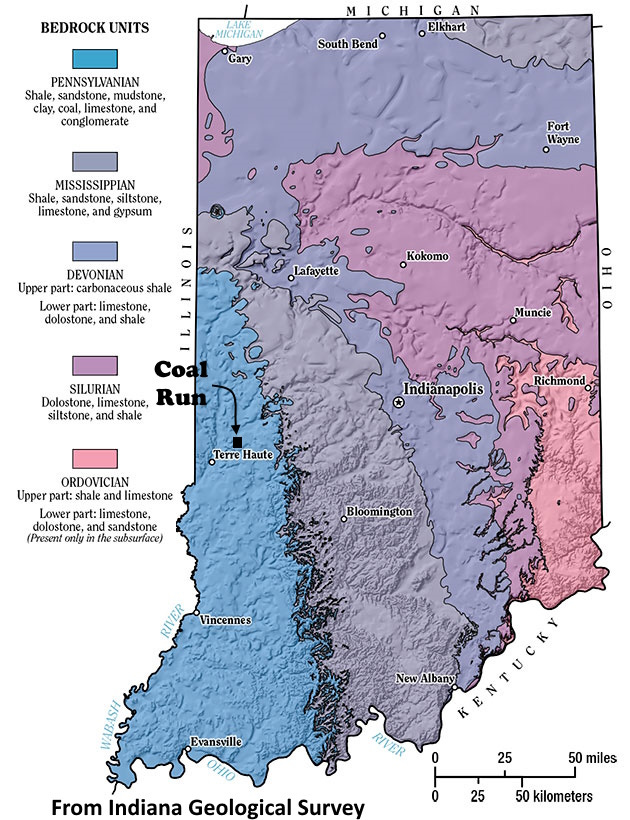

Ditomopyge olsoni is a Pennsylvanian-age trilobite from the Staunton Formation near Coal Run, Clay County, Indiana. By Middle Pennsylvanian time, Desmoinesian (Late Carboniferous), about 308 million years ago, trilobites were definitely on the decline from their peak of diversity, on the way to final extinction as a group at the end of the Permian, about 252 million years ago, following a run of almost 290 million years.

The extinction of trilobites along with many other plants and animals at the end of the Permian was not an abrupt thing for these arthropods – trilobites had significant erratic ups and downs, but overall a decline from the end of the Cambrian 488 million years ago (and the following Ordovician Period), when there were at least 63 trilobite families comprising thousands of species, to only 4 families in the middle Pennsylvanian Period when Ditomopyge olsoni lived.

Many of the coal-bearing sandstones and shales of the Pennsylvanian Period were laid down in stagnant environments that were not exactly conducive to trilobites, which typically lived in well oxygenated, if sometimes muddy, marine environments. Trilobites are unusual in any rocks of Pennsylvanian age, but of them Ditomopyge olsoni is one of the most common.

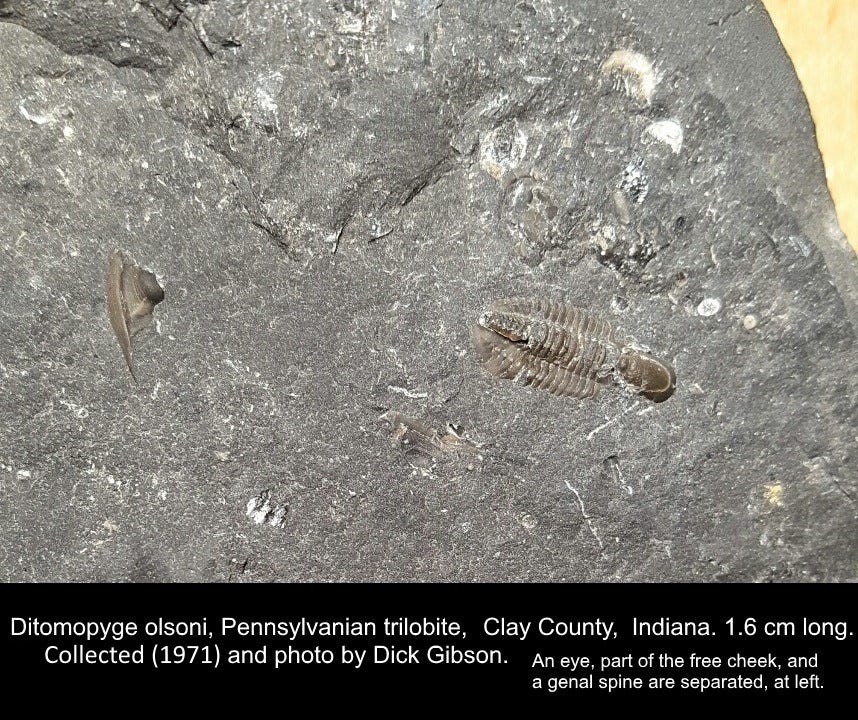

My specimen, which I collected in 1971, is in a dark gray, almost black limestone, along with fragments of crinoids and brachiopods. Elsewhere in the Staunton Formation a rare species of extinct cartilaginous fish has been found. All this suggests that the rock was deposited in a shallow marine environment.

The Staunton Formation in western Indiana is interbedded sandstones, shales, and at least seven small coal beds and three limestone members. All that variation probably reflects sea-level changes during the Pennsylvanian Period, which in turn were caused by variable pulses of glaciation. The glaciers were on continents that are now mostly in the southern hemisphere, and they were even closer to the south pole.

What is now Indiana, and much of central North America and western Europe, were near the equator when Ditomopyge lived. There, episodic advance and retreat of the distant glaciers probably caused those sea-level changes that produced the alternations between swamps, during low stands of sea level, and incursions of the sea when the water was deeper as the ice melted. This alternation is what produced the rhythmically alternating layers of coal and sediment in Pennsylvanian or Late Carboniferous strata around the world. For more about Pennsylvanian paleogeography, see this post at The History of the Earth.

The separate eye, free cheek, and genal spine at left probably broke from the main body of the trilobite, which is 16 mm long, after it died. The other eye and free cheek were probably mostly on the facing rock surface, and their impressions and fragments are poorly visible just to the lower left of the main body of the trilobite.

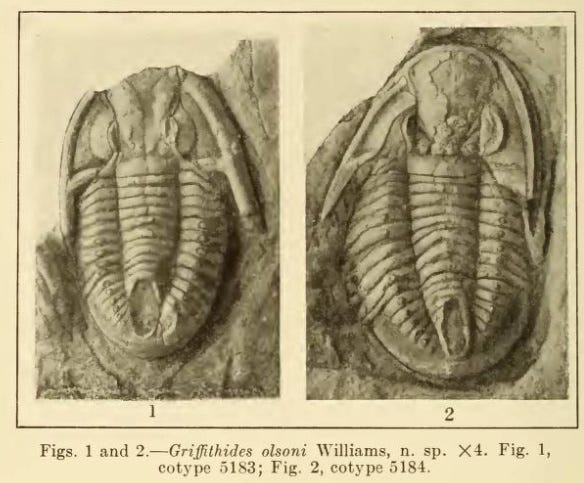

Di-tomo-pyge is from Greek words meaning “two cut (or section) rump (or tail)” for divisions in the pygidium or tail section of members of the genus. “Olsoni” is for W.S. Olson of Columbia, Missouri, who collected one of the co-type specimens in Missouri with James S. Williams of the USGS in 1929. Williams named the original species Griffithides olsoni, but it was assigned to Ditomopyge in 1935.

Although I don't generally keep up on palentological news, but your post reminded me that Dr Richard Fortey trilobite expert and science communicator (BBC, etc.) just died earlier this week (3/7). Among his popular science books Trilobite!: Eyewitness to Evolution was a candidate for the Samuel Johnson Prize in 2001. I came across him as a guest on the podcast GEOLOGY BITES discussing Deep Time. He was also on an episode on trilobites as a geochorometer.