Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

Construction of the present Durham Cathedral in northeastern England was begun in 1093 and continued for centuries. The main part of the Chapel of the Nine Altars was built in 1242 to 1280, and many of the column facings and other decorations are made from a rock called Frosterley marble.

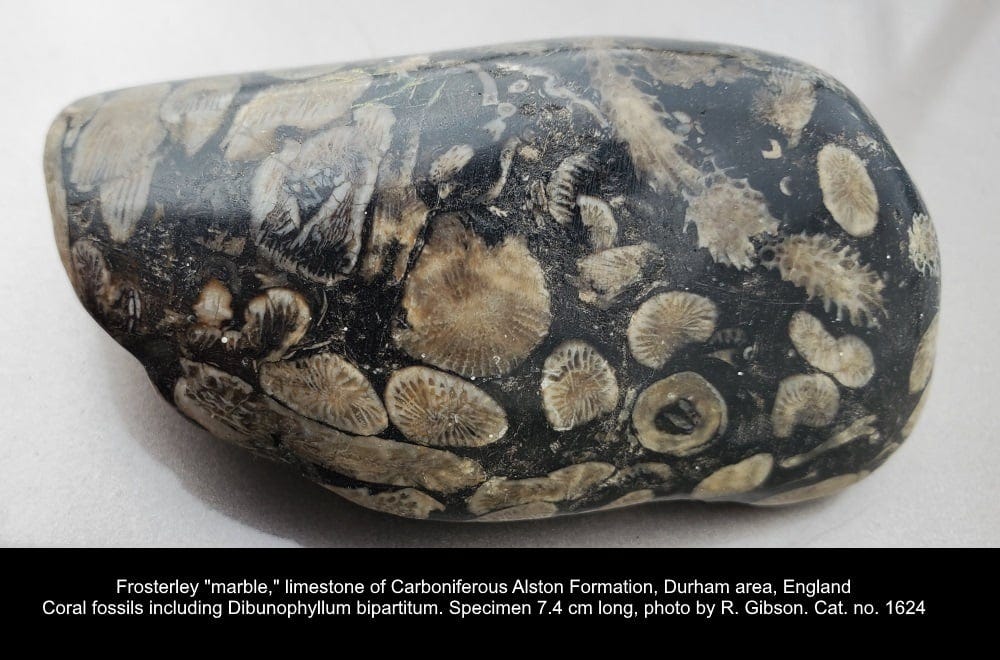

It isn’t really marble in the geological sense of metamorphosed limestone, but is a dark (black to very dark brown) limestone that takes a polish well. It contains abundant fossils, especially corals and especially a distinctive coral named Dibunophyllum bipartitum.

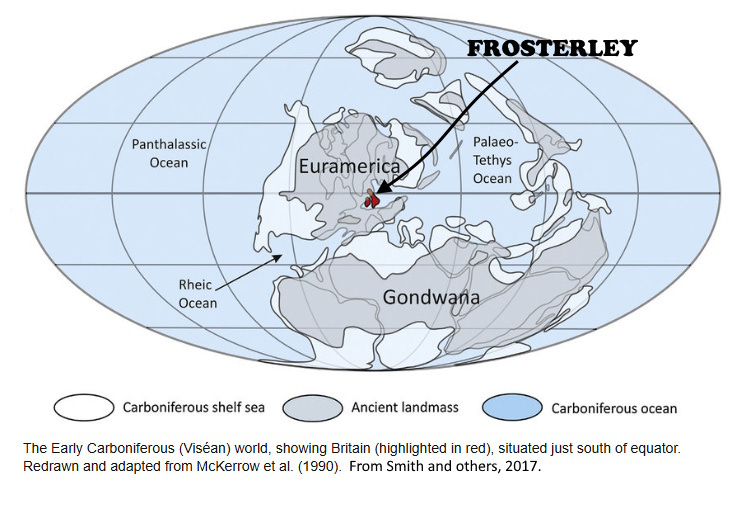

The corals lived in warm equatorial seas during the Viséan to Serpukhovian stages (Asbian, Brigantian and Pendleian in British stratigraphy) of the early Carboniferous period about 330 to 325 million years ago. The dark limestone is a thin layer, often no more than a meter thick, within the Alston Formation. In many places the Frosterley limestone is only about 20 cm thick, but it is persistent over many hundreds of square kilometers (Tucker and others, 2009, Are beds in shelf carbonates millennial-scale cycles? An example from the mid-Carboniferous of northern England: Sedimentary Geology 214: 19–34).

325 million years ago, northwestern Europe had already become attached to Greenland and North America as part of the amalgamation that would become the supercontinent Pangaea. In Europe that amalgamation is called the Caledonian Orogeny or mountain-building event, and in North America the related set of tectonic events is called the Acadian. After a pause of about 80 million years, additional collisions began that pushed Gondwana (Africa and broken pieces along its northern margin – today’s Iberia, Italy, and other blocks) against what is now northern Europe.

By the early Carboniferous, southern England, northern France, and Germany were close to the front of that second collision, which is called the Variscan Orogeny. Northern England was a relatively stable zone, but near enough to the action that faulting broke that area into elongate troughs and ridges. Some of them lasted long enough to admit arms of the sea in which the corals flourished, but the troughs or basins were often restricted. That’s probably why the Frosterley limestone is black – the abundant organic material in it settled to the bottom of a restricted basin so it was not disturbed or oxidized, and became incorporated into the rock along with the corals themselves when they died.

The fact that the Frosterley zone is so thin is one indication of the short time interval over which its depositional basin lasted, probably less than one or two million years and maybe much shorter. The Great Limestone of the Alston Formation, of which the Frosterley is part, represents one element of the cyclothems that dominate Carboniferous stratigraphy. A cyclothem is an alternating sequence of rocks that indicate alternating rises and falls of sea level. In North America, the coal beds of Pennsylvania show cyclothems in coal that formed in stagnant swamps alternating with more sandy layers carried by rivers. In northern England, the response was more typically continental deposits (rivers, lakes, hill slopes) alternating with short incursions of the sea, indicated by the Frosterley zone.

The sea level changes that produced the rhythmic cyclothems during the Carboniferous have been attributed to pulses of glaciation sucking up and then releasing vast amounts of sea water. The glaciations in turn have been related to Milankovich cycles, periodic changes in the Earth’s axis geometry which affect how much solar radiation the planet receives. Tucker et al. (cited above) believe that they have identified millennial-scale packages of layers within the Great Limestone Cyclothem, packages that were deposited in a few thousand to a few tens of thousands of years. Recognition of such short time-scale aspects of the geologic record 325 million years ago is astonishing, but Tucker et al. make an intriguing and convincing case.

The coral fossils have a distinctive brownish color which you can see in the photo of my polished specimen. The corals are a random mix of many individuals, suggesting that storms (or even just one storm) ripped them up en masse from their shallow-water homes and then carried the broken corals into deeper water where they settled into the black anoxic organic-rich limy bottom sediment to become incorporated into this, the Frosterley limestone.

Frosterley, a place near Durham, was originally named “Forsterlegh,” meaning the forester's clearing.

Appreciate your paying a visit to us in the UK! Another fossil limestone, the Purbeck "Marble", decorates Salisbury Cathedral. Jurassic snails. Most of our Mediaeval cathedrals have some interesting geology...