It’s from Lake Jaco

No, it isn’t.

Lake Jaco, Chihuahua, Mexico, is a famous locality for beautiful diversely colored garnets, especially raspberry and pink grossular, as well as vesuvianite. I’ve had the vesuvianite crystal above since the 1960s when I paid 50 cents for it from Minerals Unlimited.

But in reality, there are no specimens from Lake Jaco. It’s a dry playa lake about 200 km southeast of Chihuahua. If there are any collectible minerals there, they might be halite or gypsum or some other evaporite. The story of how California mineral dealer George Burnham came to label his garnet and vesuvianite specimens as from Lake Jaco in the 1950s is told on MinDat here, where you can also see examples of the raspberry red garnets. The upshot amounts to keeping a prime collecting locality secret, together with a landowner who didn’t want crazy collectors trooping across his land. A similar story is related from the 1970s with mineral dealer Benny Finn (Lueth and Jones, 2003, Red Grossular from the Sierra de Cruces, Coahuila, Mexico: Min. Record 34:6). Although the correct locality has been known for years, you still see specimens labeled “Lake Jaco” – I got one in 2023, and every specimen from there that I have was originally labeled “Lake Jaco.”

The specimens are from Sierra de Cruces (incorrectly Sierra de la Cruz, or Sierra de las Cruces), Sierra Mojada municipality, Coahuila, Mexico – not even in Chihuahua State, although the border isn’t too far away. The Sierra de Cruces is a small, nearly circular mountain range about 20 km east of Lake Jaco, south of the iron mining town of Hércules.

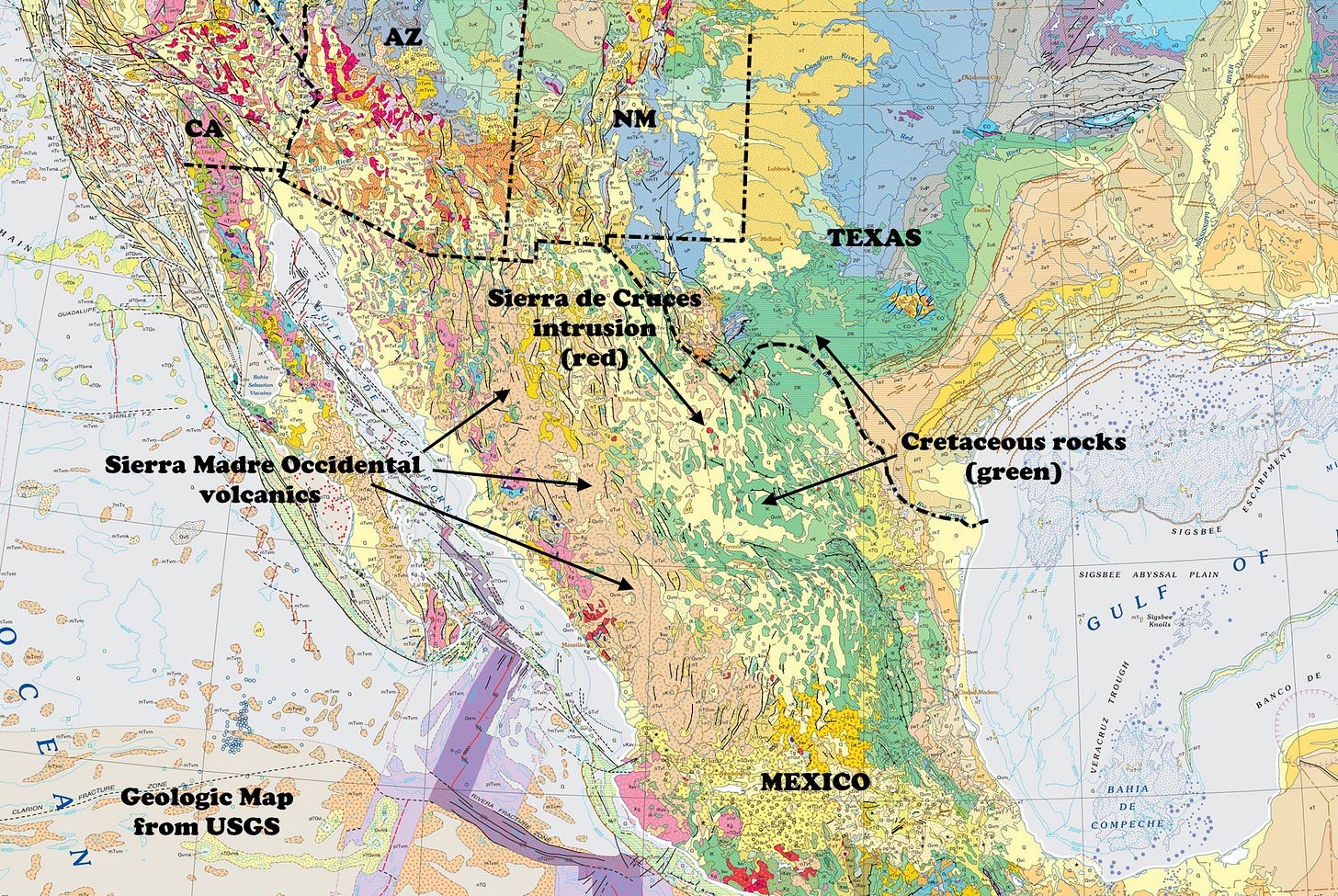

The near circularity of the Sierra de Cruces suggests that it might be a dome, and indeed there’s a 35-million-year-old diorite intrusion there that pushed up Cretaceous limestones. The intrusion also metamorphosed and metasomatized (introduced new chemicals into) the limestone to make marble and skarns (altered rocks) near the contact zone. That’s where the garnets and vesuvianite are found – they are both typical minerals in limestone skarns.

The Cretaceous limestone is part of a broad expanse of shallow marine rocks that extends into Texas and through much of the western United States. The igneous activity 35 million years ago is coeval with the huge Sierra Madre Occidental igneous province of western Mexico, which dates to about 70 to 30 million years ago and represents the complex interaction between southwestern North America and island arcs and subduction zones that added to the continent and formed much of western Mexico.

Apparently the skarn zone containing the raspberry-red garnets is a pretty local feature, only about 4 x 4 x 13 meters (Lueth and Jones, 2003), but other colors of garnets (like my pink and green garnets shown here) and vesuvianite occur in much more extensive areas in the overall skarn zones.

Grossular, originally named for specimens the color of green gooseberries, Ribes grossularium, is ideally Ca3Al2(SiO4)3, but analysis of the red specimens (Geiger and others, 1999, Raspberry-red grossular from Sierra de Cruces Range, Coahuila, Mexico: Eur. J. Mineralogy 11:1109-1113) shows that they contain magnesium and manganese in the calcium molecular position and iron and manganese in the aluminum position.

Geiger and others (1999) infer that the unusual red color is related to the exact proportions and positions of the iron and manganese in the garnet crystal structure. Other colors (pink and greenish are common at Sierra de Cruces) are produced by different proportions, and some of the specimens might have enough iron to be considered andradite garnet, ideally Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3. A series extends from andradite to grossular so all variations between the two end members are possible. Likewise, there’s a series from grossular to pyrope, Mg3Al2(SiO4)3, but Geiger and others (1999) don’t seem to see a relationship between the red grossular and magnesium content. There’s yet another series between grossular and spessartine, the manganese-aluminum garnet.

Color in garnets can be highly suggestive, but not a distinguishing characteristic for the species. Grossular ranges from colorless to very dark brown. I did a little x-ray diffraction project in college to see if color was a valid discriminant between pyrope and almandine garnets from Montana; the answer was no.

I have a specimen or two to rename methinks!