Ivanhoe Mine

Montana's largest tungsten producer

Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

The Ivanhoe Mine, between Brownes and Agnes Lakes in the East Pioneer Mountains of Montana USA, was a tungsten mine (although established initially for copper, in 1902, and mined for copper in the late 1920s), active mostly in the 1950s and sporadically thereafter. It was the leading producer of tungsten in Montana in the mid-1950s. Today, the United States has no primary mine production of tungsten, and apart from recycled and other secondary production, is entirely dependent on imports, with China the leading supplier in 2024; China produces more than 82% of world tungsten, with Vietnam a very distant second with 4% of mine production. The greatest volume of tungsten consumption in the U.S. goes to making tungsten carbide for cutting tools in the construction, metalworking, mining, and oil and gas drilling industries.

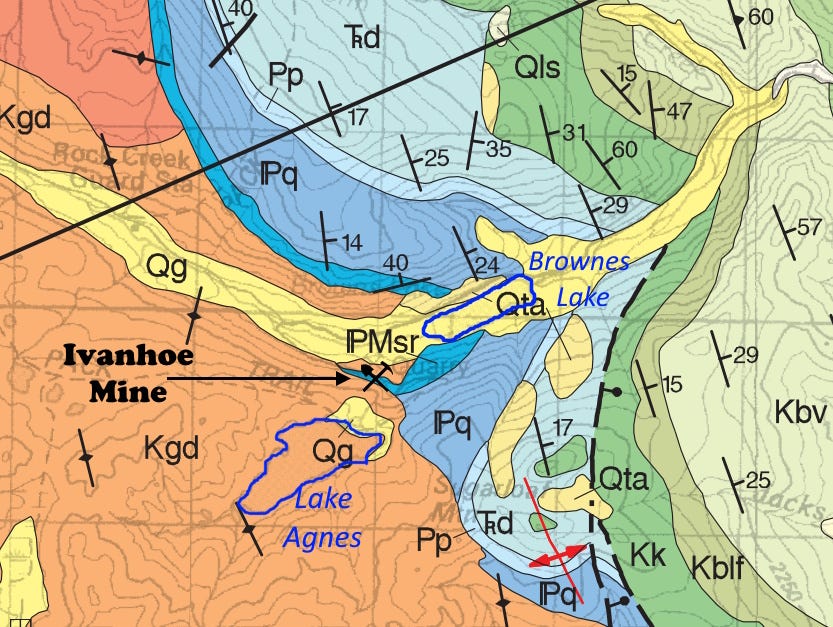

The tungsten and other ores including copper and silver are likely related to fluids that came from the Mt. Torrey Batholith, part of the Pioneer Batholith (Kgd, orange on the map above). That’s a large granitic intrusion, comparable in composition and age to the larger Boulder Batholith. Both the Pioneer and Boulder Batholiths were intruded around 75 million years ago.

The Ivanhoe Mine is in contact metamorphosed limestones of the Snowcrest Range Group (PMsr, bright blue on the map), mostly marine sandstones, siltstones and limestones that were deposited during late Mississippian and early Pennsylvanian time (Carboniferous), about 325 to 340 million years ago. The limestones are probably part of the Lombard Limestone. The Snowcrest Range Group is a newer name for rocks previously mapped as the Amsden Formation in this area.

The sedimentary rocks more or less sat there quietly for around 250 million years until the intrusive batholith both metamorphosed the limestone and tilted the sedimentary rocks. The sedimentary rocks surround the eastern flank of the granitic batholith in a generally concentric manner, with the oldest (Mississippian age) rocks adjacent to the batholith, and younger rocks further east. It’s quite complex locally, but overall, it’s a pretty straightforward dome-like arrangement in this area, pushed up by the intrusive batholith like a rising blob in a lava lamp about 75 million years ago.

The magnetic map above (from USGS, 2025) shows the position of the Ivanhoe Mine on the flank of the Pioneer Batholith (the big red magnetic high in the southwestern part of the map). One might ask, why is there tungsten mineralization at the Ivanhoe Mine but not all along the margin of the batholith? The easy cop-out answer is that the conditions there were just right for the mineralization to occur. The nature of the host rock (the Snowcrest Range Group), the composition of the molten rock in the batholith, the temperature and pressure conditions, presence of things like faulting to provide conduits for mineralizing fluids emanating from the batholith, all that and more may help constrain the location of mineralization. The site of the Ivanhoe Mine may have been a Goldilocks position – just right for the deposition to occur.

Conceivably, there might have been additional similar deposits along the batholith margin. Some of them may have been higher than the Ivanhoe Mine location (i.e., up in the air now, and eroded away), and possibly there are more such locations deeper in the subsurface along the margin. The Ivanhoe Mine location might be exposed at the surface today simply because of the vagaries of erosion.

Also, if you look closely at the geologic map above, you see that the mine is in a small sliver of the Snowcrest Range Group, with igneous rock on either side. It could be that the mineralization focused here because the bit of country rock was almost enclosed by the igneous material, giving more options for the minerals to come in.

The photo at top (from October 2016; Phil Dobson for scale near center) shows the layered, metamorphosed sediments. The inset shows a slab of garnets, typical minerals in contact metamorphism of limestone (repeated with others in the montage below). The token is about 37 mm across. Invisible at this scale are abundant millimeter-size grains of white scheelite, calcium tungstate, which was probably the primary tungsten ore for the mine. Scheelite here is brightly fluorescent, as scheelite usually is, so even tiny specks of it are easy to find in the rock by using an ultraviolet light source.

If you happen to go to this mine, which is on a side trail branching from the trail to Agnes Lake, be aware of the possible hazard from rocks falling from the near-vertical flanks of the old open pit. Also note that the site is a patented mining claim, now (2025) posted.

A bit off topic but my former coworker Bob Koehler says hi.

The Goldilocks positioning explanation for why mineralization concentrated at Ivanhoe specifically makes more sense than I initially thought. I've seen similar localization patterns in other contact metamorphic settings but never connected it to that combination of host rock composition plus fault conduits plus the right spot relative to erosion levels. The fact that the US produces zero primary tungsten now but was pulling significant amounts from this one site in the 50s is wild given how critical tungsten carbide is for industrial tooling. That dependency shift hapened so quietly.