On March 7, 1785, in some ways, the modern science of geology was born. On that day the first of two papers by James Hutton was read before the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland. The pair of papers was entitled Concerning the Systems of the Earth, its Duration, and Stability, and these papers, with little change, formed the core of Hutton’s Theory of the Earth, published in 1795. Many of the ideas first clearly expressed there serve as the basis for modern geology.

Hutton was born June 3, 1726, son of a Scottish merchant who was Treasurer of the City of Edinburgh. Hutton’s early interest in chemistry led him into medicine – he was a practicing physician – and ultimately into geology.

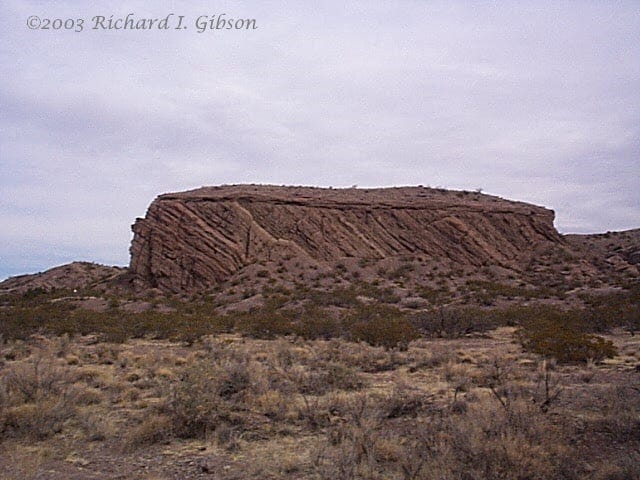

Hutton studied unconformities (breaks in the rock record), cross-cutting relationships, and the tilting of formerly horizontal strata to come to his famous conclusion, expressed later by Charles Lyell as “the present is the key to the past,” the idea that processes operating today must have operated in the past, and that they produced the features we see now. Hutton actually wrote, "from what has actually been, we have data for concluding with regard to that which is to happen thereafter."

An important aspect of his conclusion was that while there was much change over the course of earth history, the processes were fundamentally the same, and operated continually. This led to his famous concluding statement, "The result, therefore, of our present enquiry is, that we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end." Today we call this uniformitarianism, a big word that just says the processes affecting things on earth happened uniformly over geologic time.

At the time there was plenty of opposition to Hutton’s ideas. Prevailing thought included the catastrophists, who believed that short intense events (like Noah’s Flood) created the things we see in the rocks, rather than the gradual effects of erosion, deposition, and multiple relatively small tectonic events such as earthquakes. In fact uniformitarianism was sometimes called gradualism.

Hutton was also opposed by the Neptunists, who were in their own fight against the plutonists. Neptunism suggested that everything was formed in the sea, and plutonists said everything came from molten, volcanic origins. Hutton’s ideas allowed for a nice compromise between those two fairly rigid and extreme views and gave room for both processes and gave both considerable importance.

The ultimate adoption of the concept of gradual change, uniformitarianism, became so well entrenched in geological thought that even into the middle part of the 20th century, the idea of any kind of catastrophe was ridiculed. Consequently, when Luis and Walter Alvarez suggested, in 1980, that a catastrophic impact caused the extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period that wiped out the dinosaurs, there was considerable laughter at the idea. The good news is that the idea was tested scientifically, and the evidence mounted, culminating in the discovery of the “smoking gun” -- a huge crater in the subsurface of Yucatan that has been dated to just the right time.

Today, I would say that geologists firmly believe that uniformitarianism has been the dominant factor in the evolution of planet earth – but there have indeed been some changes in the processes affecting the planet over its 4.6-billion-year life, and there have indeed been some highly influential catastrophes too.

The word “uniformitarianism” was coined in 1832 by William Whewell, the English polymath who also invented the words scientist (for a woman) and astigmatism, and for whom the kidney-stone mineral whewellite (calcium oxalate) was named.

The case can easily be made that Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov (1711-1765) preceded Hutton in expressing modern concepts of geology, in his On The Strata of the Earth (1762), wherein he discussed the consistent nature of earth processes and considered the present nature of the Earth as the means of understanding its past.

Even though the Enlightenment was in full swing in Europe in the 1700s, and Lomonosov’s work was likely known to other European scientists, there can be little doubt that Russian work was less prominent at the time than that of German, French, and British geologists.

James Hutton clearly expressed the basic concepts that govern modern geologic thought, in March 1785, and because of the influence of early English-speaking scientists, he’s called the Father of Geology. But if you want to give that name to Lomonosov too, I’m not about to argue.

Here in Scotland I've visited three of the classic Hutton sites at Siccar Point, Arthur's Seat and Glen Tilt - his Unconformity (like the one in your picture) showing the immense time period between the two layers and the other two showing the Plutonic, or igneous, nature of granite and basalt. Origins of geology more fun when you're living on top of them. Hope you're coming to Scotland some day!

Love this! As a Hutton, I definitely thought I was getting an email from my cousin when this popped up on my email.