The Krivoy Rog Iron region of Ukraine holds a huge deposit of banded iron formation about 2,000 to 2,200 million years old (Paleoproterozoic time). It is a sedimentary deposit similar to the iron ores of Upper Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, although there seems to be a lot more magnetite in the Ukraine deposits versus hematite in the Lake Superior region.

Banded iron formations worldwide reflect the oxygenation of earth’s atmosphere. Iron oxide precipitated out of ocean water that was saturated in iron, at a time when most oxygen was in the waters and not in the atmosphere. Once those reactions had more or less gone to completion, meaning most of the iron had precipitated out as oxides (hematite and magnetite), free oxygen that was generated by photosynthesizing cyanobacteria was able to enter the atmosphere, ultimately allowing for oxygen-breathing life on land.

Mining in Ukraine for iron on an industrial scale by tsarist Russia began in the 1880s and has continued under the Soviet Union and Ukraine since. The Krivoy Rog area was one of the economic resources targeted by Nazi Germany during World War II.

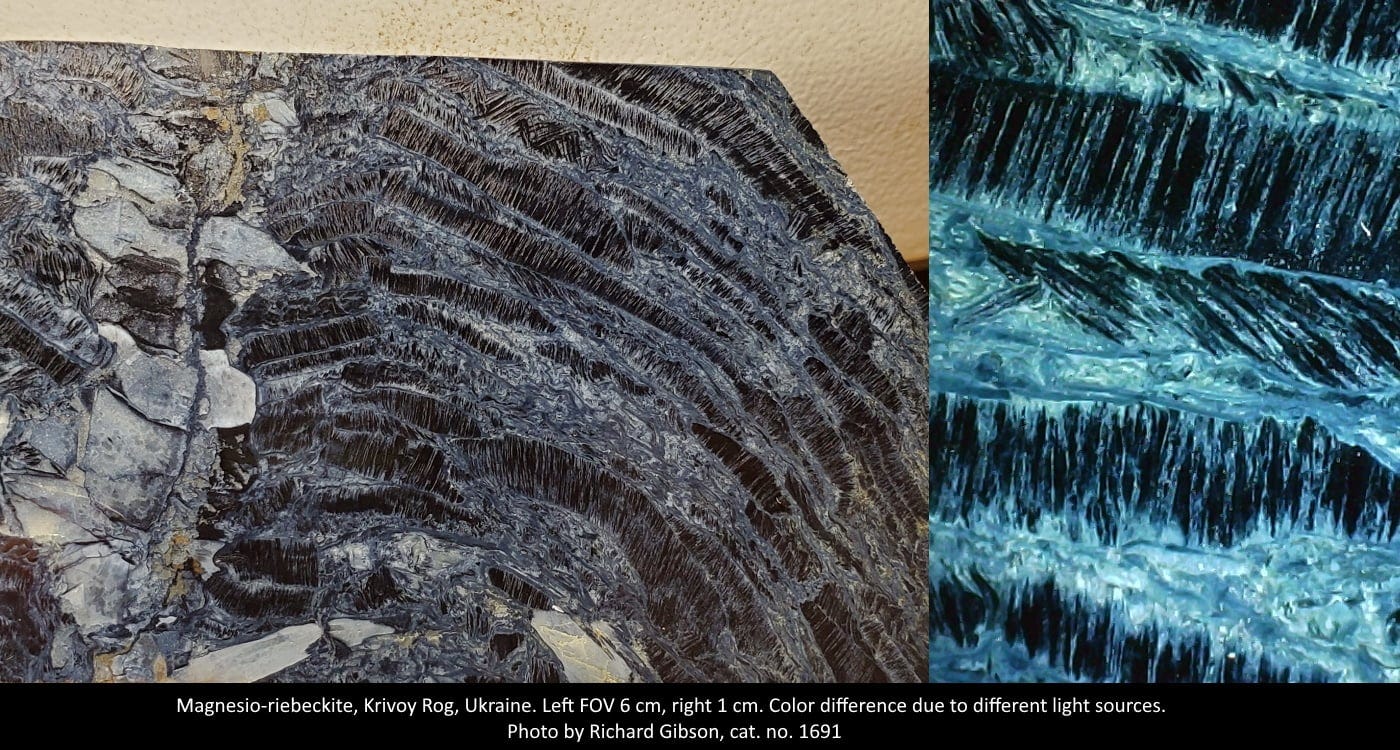

There are many rocks in the overall package containing the iron formations, including diverse schists, slates, quartzite, and marble, all of which were originally sedimentary rocks but which have been intensely metamorphosed over the past two billion years. In places, the schists contain dark blue amphiboles close to the sodium-iron end member named riebeckite. My specimen here is almost certainly the species named magnesio-riebeckite, {Na2}{Mg3Fe3+2}(Si8O22)(OH)2, for the dominance of magnesium over iron in one of the crystallographic positions; it is well known from the Krivoy Rog deposits. The area is also known as the Kryvorizkyi Iron Ore Basin (Kryvbas), a narrow belt about 100 km long in central Ukraine.

The fibrous bands, blue color, and chatoyancy (a “cat’s-eye” shimmering optical effect) are typical for the riebeckite group of minerals. When riebeckite alters to a golden hue and is sometimes partly replaced by quartz, the material is called tiger’s eye. In some cases, riebeckite can be so finely fibrous that it is called crocidolite or blue asbestos and may be managed as a hazardous substance. I’m pretty sure my specimen here is not an example of blue, unaltered crocidolite known by the trade name falcon’s eye; I think it is too coarse, and should just be identified as magnesio-riebeckite.

The blue color here is so intense that it might be enhanced by dye, but I’m pretty sure this is entirely natural. This is a cut and polished slab that was given to me in 1992 by Russian participants in a technical session I chaired at the Society of Exploration Geophysicists’ convention in Moscow in July of that year.

Riebeckite was named for German explorer and mineralogist Emil Riebeck (1853–1885). Crocidolite is from Greek words meaning “nap of cloth” for the fine, tight, thread-like texture. Krivoy Rog, known today as Kryvyi Rih, is from Ukrainian for “crooked horn,” probably an allusion to the geography of the confluence of the Saksahan and Inhulets rivers. Kryvyi Rih is the most important iron-mining and steel-making city in Eastern Europe. Cat. No. 1691.

The farewell party for the SEG convention in Moscow in 1992 was held at Catherine the Great’s palace (below). If you are interested, you can find my travelogue of that visit here. Remember the context – that piece was written in 1992.

Fascinating comment re the oxygenation of Earth's atmosphere!

Great travelogue. You write so well.