Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance and promotion of science. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them.

This bit of native silver was probably mined in 1967 or earlier from the Lavaderos Mine in Sonora, Mexico; the specimens were wrapped in 1967 newspapers. The deposit is a lead-zinc skarn, a rock altered by contact and chemical exchange with Eocene granitic igneous intrusions and rhyolitic volcanics. The situation is complicated by a Miocene detachment fault, the El Amol fault, which cuts the mineralized zones (Calmus, T., Pérez-Segura, E., & Roldán-Quintana, J., 1996, The PB-Zn ore deposits of San Felipe, Sonora, Mexico: "Detached" mineralization in the Basin and Range Province: Geofísica Internacional, 35(2), 115-124). The skarn host rocks are both volcanics and limestones that are probably Cretaceous in age.

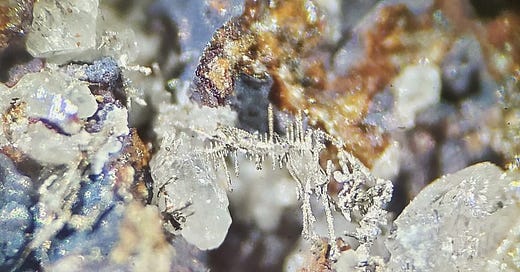

The silver in the photo at the top shows a nice herringbone or trellis structure, typical of native silver. The whole thing is about 2 or 3 mm across. The white crystals it is growing on are probably anglesite, lead sulfate, but there is cerussite, lead carbonate, in the deposit as well and it’s really hard to tell anglesite and cerussite apart visually, because they have similar crystallography and properties.

Nonetheless, I’m confident that I can discriminate between cerussite and anglesite in these specimens. The cerussite tends to occur in larger crystals (with occasional partial sixling twins, which are diagnostic) that are more vitreous and more striated than anglesite, which tends to have stubby to bladed forms terminated with typical wedge-shaped faces. And despite my suggestion that the silver above is on anglesite, silver seems to occur more often in close association with cerussite (meaning directly on the crystals) rather than anglesite, as on the cerussite crystal at center in the photo below.

Lavaderos is a fairly obscure little mine (there are only 7 photos on MinDat from there), and I’m not certain it really ever produced much, but there are hundreds of micro examples of native silver in the specimens I got. Mining in the area is active, with a relatively new open pit and underground mine operated by Americas Gold & Silver Corp., a Canadian company. In their deposit, they report silver grades averaging 63 grams/ton (i.e., more than two ounces per ton), lead at 1.7%, and zinc at 5.1%.

I collect microminerals for several reasons: they don’t take up much space, they are cheap, and they often show levels of excellent crystallization and relationships that you’d have to pay thousands of dollars to find in a cabinet specimen (and often enough, bigger specimens just don’t show the excellence of crystal form that tiny crystals can display).

What does a nerdy micromineral collector do when it’s too smoky for a bike ride? He goes through the “shreds” of samples that crumbled off the main pieces, looking for bits of native silver. After hours of tedious, back-breaking work hunched over the microscope, the result is the two little boxes shown here. Each little spot there is a bit of arborescent or wire silver, most of them not even a millimeter long.

The photo through the microscope a couple paragraphs up show some representative examples. Some are obviously silvery; the black ones have a tarnish or alteration to acanthite, silver sulfide, on the surface.

I also picked out good crystals of anglesite and cerussite from the material.

The famous adamantine green anglesite crystals from Sardinia are perhaps colored by inclusions of copper or a copper mineral, but despite extensive searching I could not find a definitive study of their color. My example above from Lavaderos contains translucent, not adamantine crystals. No copper mineral is reported from Lavaderos, but I think it’s a minimally studied locality, and copper would not be very unusual.

Anglesite was first recognized as a mineral species by William Withering in 1783, who discovered it in the Parys copper-mine in Anglesey, Wales. The name anglesite, from the island, was given by F. S. Beudant in 1832. Contrary to popular belief, the Island of Anglesey does not refer to the Angles, the post-Roman Germanic people who settled Great Britain, and whose name comes to us in Anglo-Saxon and the name England (Ængla land). The island’s name more likely comes from Old Norse for “hook island” or Ǫnglisey, "Ǫngli's Island." Who Ǫngli was is not recorded.

The tiny spray of silver above is about two millimeters high. It sits on a cerussite crystal. The fuzziness of the upper part of the upright silver crystal is partly due to my inability to capture a sharper photo, but it is also partially encrusted with acanthite crystals.

The green gypsum from Pernatty Lagoon in South Australia is a similar green to your specimen Richard. Even though it is in a copper producing area (Mount Gunson mines), the green is due to iron.

They're certainly very pretty and excite the imagination. It's crazy that someone thought to throw a ton of those into a furnace to extract only the silver.