The Bunker Hill Mine in Idaho USA is among the most famous in the world for its gemmy, lustrous yellow-green and orange pyromorphite, Pb5(PO4)3Cl, but a small mine about 25 km (16 miles) to the southeast has produced some very nice specimens as well. The mine is about 2 km southeast of the town of Mullan.

Three localities close to each other – the Giant Mine, Little Giant Mine, and the Upper Giant Prospect – together produced some lead, copper, zinc, silver, and minor gold, mostly before 1904. They probably all exploited the same vein system, mineralized zones that are probably related to faulting in a tight anticline in the Precambrian St. Regis Formation, part of the Belt Supergroup of thick sedimentary rocks deposited about 1,400 million years ago.

The St. Regis is part of the Ravalli Group, about the middle of the thick package of Belt Supergroup rocks. It’s mostly sandstone, siltstone, and argillite (densely lithified mudstone), as much as 900 m (2,953 ft) thick.

This area was re-evaluated at least twice after its primary production ended about 1904. In 1927 a review by Oscar H. Hershey checked the three old tunnels, referred to as Little Giant #1, #2, and #3, which probably correlate with Giant, Little Giant, and Upper Giant. Each was about 120 to 330 feet long, and they exploited at least two zones, the Big Iron (Tunnel #1) and Little Giant (Tunnels #2 and #3) veins. I think the examination in 1927 was for lead. Hershey was not optimistic about the Big Iron vein, which he called “a magnificent iron vein but I would not give 10 cents for it for any other metal.” But the other tunnels, on the Little Giant vein, had showings of galena and barite, and Hershey assayed some pieces that held 1.2% to 1.9% lead and 0.4 to 1.4 ounces per ton of silver. He thought the deposit might pay back an investment but wasn’t optimistic for much more.

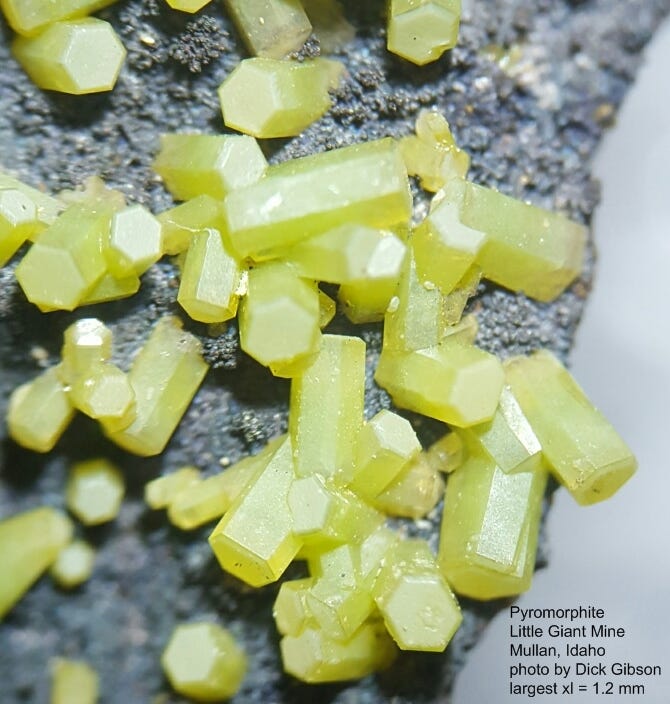

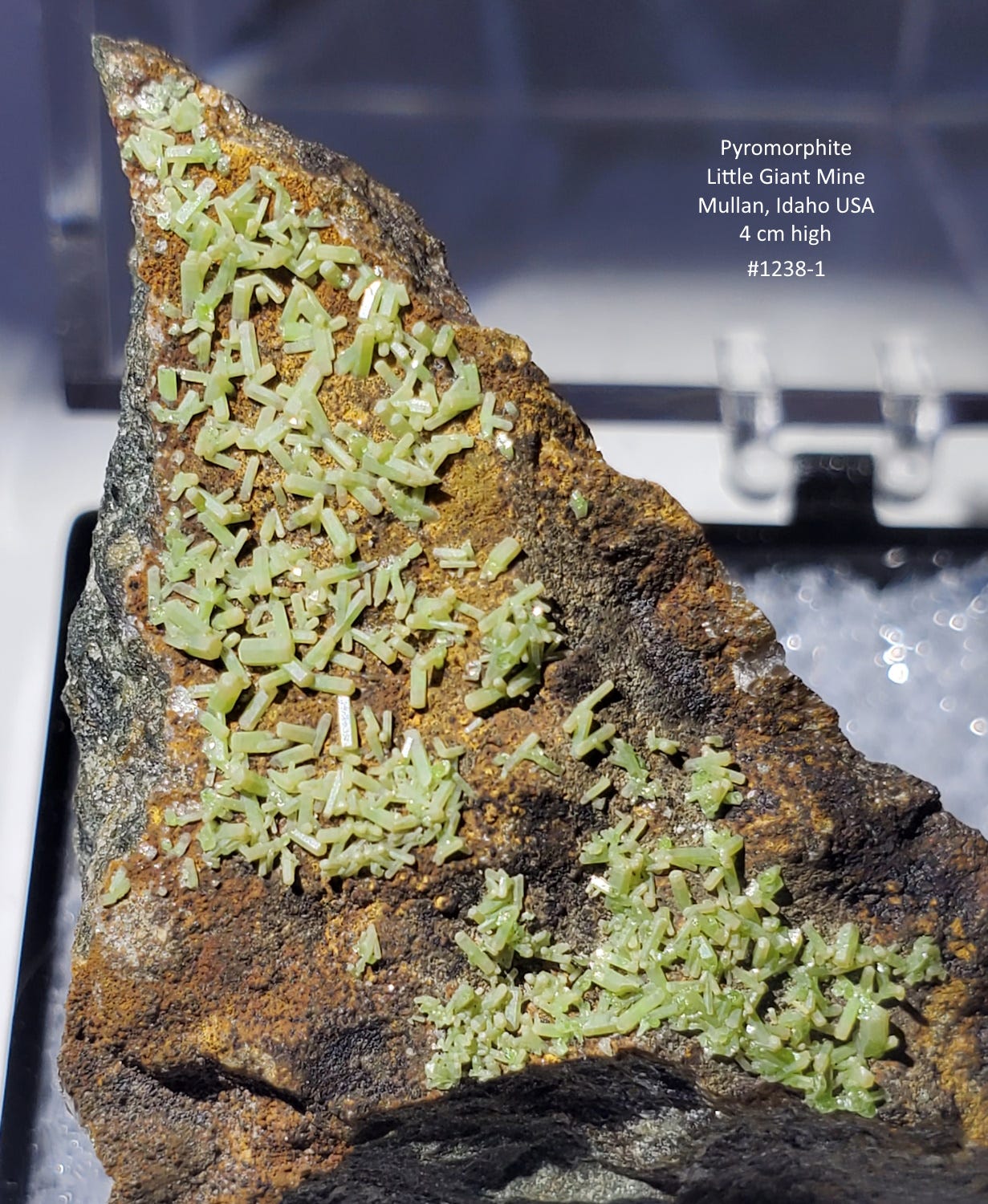

In 1966 Donald C. Long, mine geologist for the Bunker Hill Company, reported barite, siderite, galena, and pyromorphite in the Little Giant vein. He recommended to Bunker Hill that they acquire a zone just west of the Little Giant area. If they did, I’m pretty sure no further exploitation occurred, so the last real mining here was in 1904. Specimens of pyromorphite have probably been collected on the dumps since then.

The mineralization at Little Giant is probably part of the pervasive mineralization throughout the lengthy Kellogg-Coeur D’Alene District, a 40-mile- (64-km-) long zone most renowned for its lead and silver. Although it comprises multiple individual districts, Kellogg-Coeur D’Alene is almost certainly the second largest silver district in the world, with more than 1,000,000,000 (1 billion) ounces of silver produced. Potosi, Bolivia, is #1 with an uncertain but likely total exceeding two billion ounces. The Kellogg-Coeur D’Alene zone is part of the Lewis and Clark Line, a complex crustal-scale tectonic feature that has affected this region for more than a billion years (Sears and others, 2010, Lewis and Clark Line, Montana: Tectonic evolution of a crustal-scale flower structure in the Rocky Mountains: in Through the Generations: Geologic and anthropogenic field excursions in the Rocky Mountains from modern to ancient: Geol. Soc. America field guide). Depending a little on how you define it, the Lewis and Clark Line extends from somewhere west of Spokane, Washington, to south-central Montana, more than 500 km (310 miles), but most prominently expressed between Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and Helena, Montana. Much of Interstate Highway 90 in that section follows the Lewis and Clark Line.

I don’t usually comment in print on mineral prices – anyone can ask whatever they want for a specimen – but you can find pieces from the Little Giant for sale online at $690 to $950 for items about 8 to 11 cm (with crystals to 7 mm). I acquired the similar specimens in my photos here between 2015 and 2022, the largest at 10 cm and crystals at 5-6 mm, and the most any of them cost was $4.00 US.