"And some run up hill and down dale, knapping the chucky stones to pieces wi' hammers, like so many road makers run daft. They say it is to see how the world was made."

The lines above about geologists have been attributed to Sir Walter Raleigh, Robert Burns, and practically every other Scotsman who left a literary record. But they are from poet and novelist Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), in St. Ronan's Well, first published in 1823.

Geologists do run up and down hills with hammers to see how the world was made. Geologists make and/or use maps, whether a map of age zonation in a microscopic zircon crystal, or the entire planet Earth, or the distribution of a contaminated groundwater plume, or locations of particular minerals or geophysical responses. But maps of surface geology are certainly at the core of our efforts for many of us.

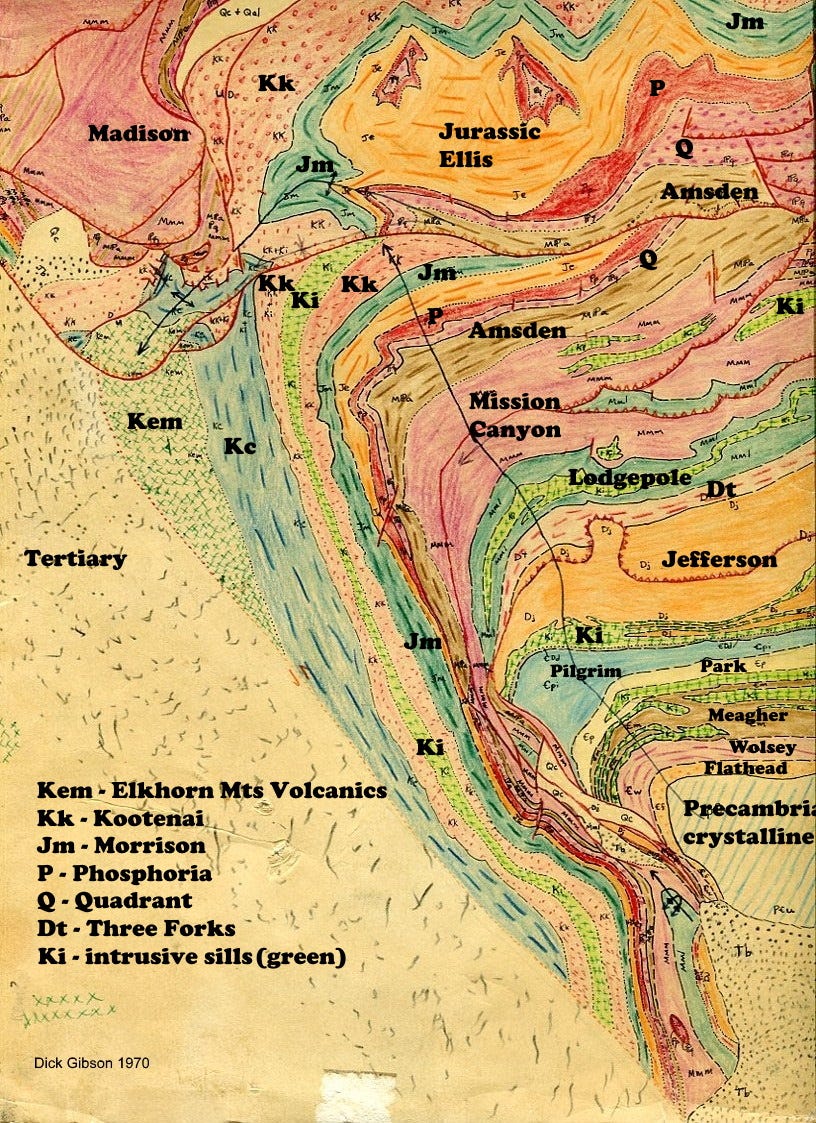

I made the geologic map above of the London Hills area, southeast of Cardwell, Montana USA, in 1970 when I was a Teaching Assistant for the Indiana University Geology Field Course. I’d certainly make some changes, even significant ones, in the tectonic interpretations (indeed, I have done so in the subsequent 5 or 6 times I mapped there) but I think in terms of the rock distributions, it’s probably pretty decent. This was back when it was easy for me to run up hill and down dale.

The area covered is about 12 square miles, and I think in 1970 this was a 7-day project. The map shows the interaction between a large high-angle northwest-trending Precambrian-basement-involved faulted anticline (“thick-skinned,” in the jargon of deformation styles) and the east-west(-ish) faults to the north which are lower-angle thrust faults involving the sedimentary section (“thin-skinned”), part of the Montana Thrust Belt. Here, the thrust belt is expressed as the Southwest Montana Shear Zone along the southern side of the Helena Salient, a persistent structural feature with heritage from at least 1,400 million years ago.

The northwest-trending basement-involved fault and fold and the east-west features to the north are fundamentally different styles of tectonic deformation that reflect the varying mechanical behavior (depending on strength, anisotropy, thickness, etc.) of the rocks present in the two areas. Although both styles have truly ancient heritage, the features mapped here developed during the Laramide-Sevier Orogeny as recently as about 55 to 80 million years ago.

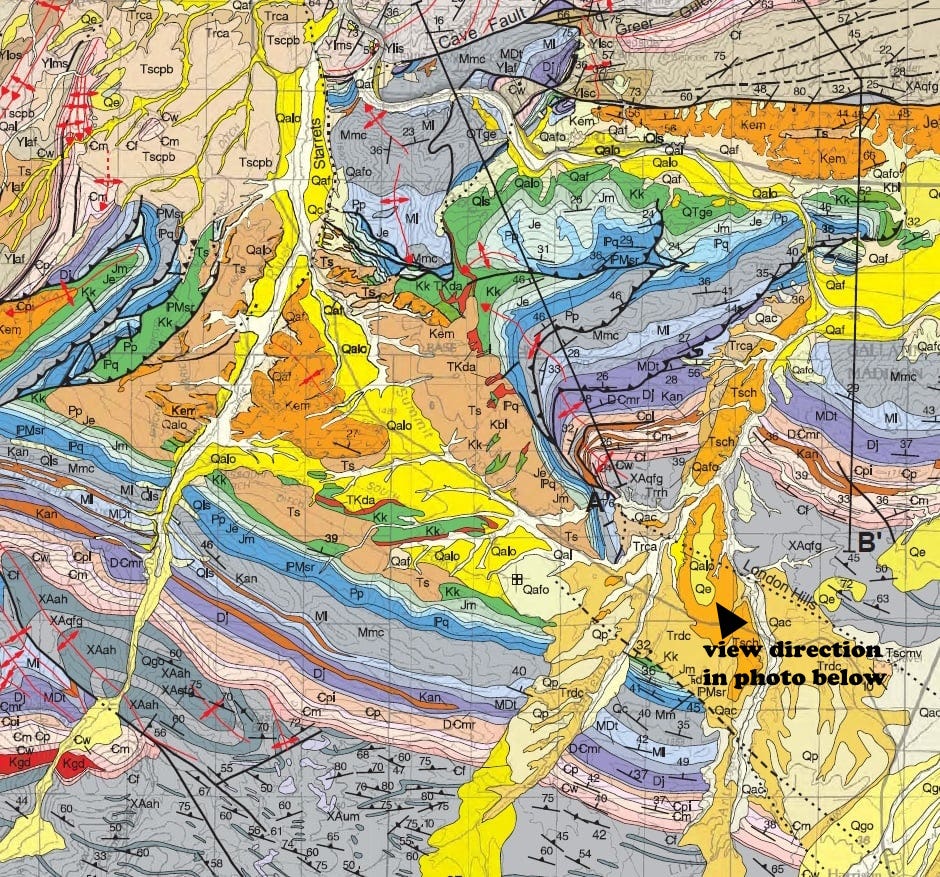

You can see the overall context (and compare to my version) in the snippet above from the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology map (Bozeman quad, Vuke, Lonn, Berg, and Schmidt, 2014).

It can be challenging to determine which came first, the northwest-trending basement fault system, or the east-west trending faults. In both my 1970 map and the 2014 Bureau map, the basement fault is shown passing into, or being overridden by, thrust faults that curve to the northeast or are east-west. The real interaction between the two styles seems to be in the subsurface in the northwestern part of the London Hills, so it is not clear which set cuts which. My opinion is that the two were nearly contemporaneous in this area, with (in my mind) a slight suggestion that the basement fault was there first, and the thin-skinned thrust faulting wrapped around the basement uplift that served as a buttress to the thrusting. It is certain that others will have other opinions, and indeed it can all be mapped to suggest that the east-west thrust faults were there first and were then folded by the basement uplift that came later (and I’ve mapped it that way in the London Hills too).

The Precambrian core of the anticline lies in the densely tree-covered area that we called the “Black Forest” because on the black-and-white air photos it was largely solid black. It’s labeled “Precambrian” in the photo above. I was in there looking for foliations to measure in the Precambrian gneiss and schist when I had my closest ever encounter with a bear in the wild: I sat down for lunch next to a narrow but fairly deep ravine. The black bear was straight across from me, probably not more than 30 feet (less than 10 meters), but we were separated by the gully, which was close to 25 feet deep. After I noticed him, I got up and quietly walked away; the bear watched me but just stayed where he was.

Earlier that same day I had been bounding “down dale,” descending the ledges in the Cambrian Meagher formation, when I hopped over a 10-inch outcrop to land directly on a coiled rattlesnake. He was more startled than I was, and didn’t even have time to rattle, much less strike. I just kept hopping down the ledges, more quickly than before and with a more loudly pounding heart. I was at least a mile away from everyone else and no one really knew quite where I was (not recommended field procedure!).

There may be some additional modification in this area by basin-and-range normal faulting, within the past 25 or 30 million years or so, as the west side (left in the photo above) of the London Hills dropped down to form a basin there, where Highway 359 runs today.

Is this a hammer which I see before me, the handle toward my hand?

Come, let me clutch thee!

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still. Art thou not, glorious hammer, as sensible to feeling as to sight?

Or art thou but a hammer of the mind, a false sensation outpouring from an alcohol-starved brain?

I see thee yet, in form as palpable as that I last week lost. Thou pointest out the way to the next outcrop, and such a hammer there I was to use.

There’s no such thing. It is this limey business that informs thus to mine eyes.

—Priscilla Nelson and Dick Gibson, 1970

I’m happy to announce the Richard Gibson–TRGS Geology Field Course Award for Excellence this year goes to Kevin Taylor from Eastern Washington University. https://www.trgs.org/_files/ugd/768db9_ca79a8bc1adf4b87a56986e3fc2743b4.pdf

Reminds me of my first and only encounter with a rattler during the U of Montana Field Camp in August 1978. Ledge stepping/hopping down a steep slope at the Block Mountain "rat's nest" field area and stepped directly over a smallish coiled rattler. He sounded off while my uphill foot was still on the ledge and I sprang forward, and WAY downhill, instantly. I remember thinking "that sound is something which the Hollywood foley artists have pretty much nailed".

That's a beautiful map you made, all those years ago.