To look at the shapes of the coastlines, you might think Madagascar rifted away from the curving coast of Mozambique and moved to the northeast. But the real rift between Africa and Madagascar is north of the island.

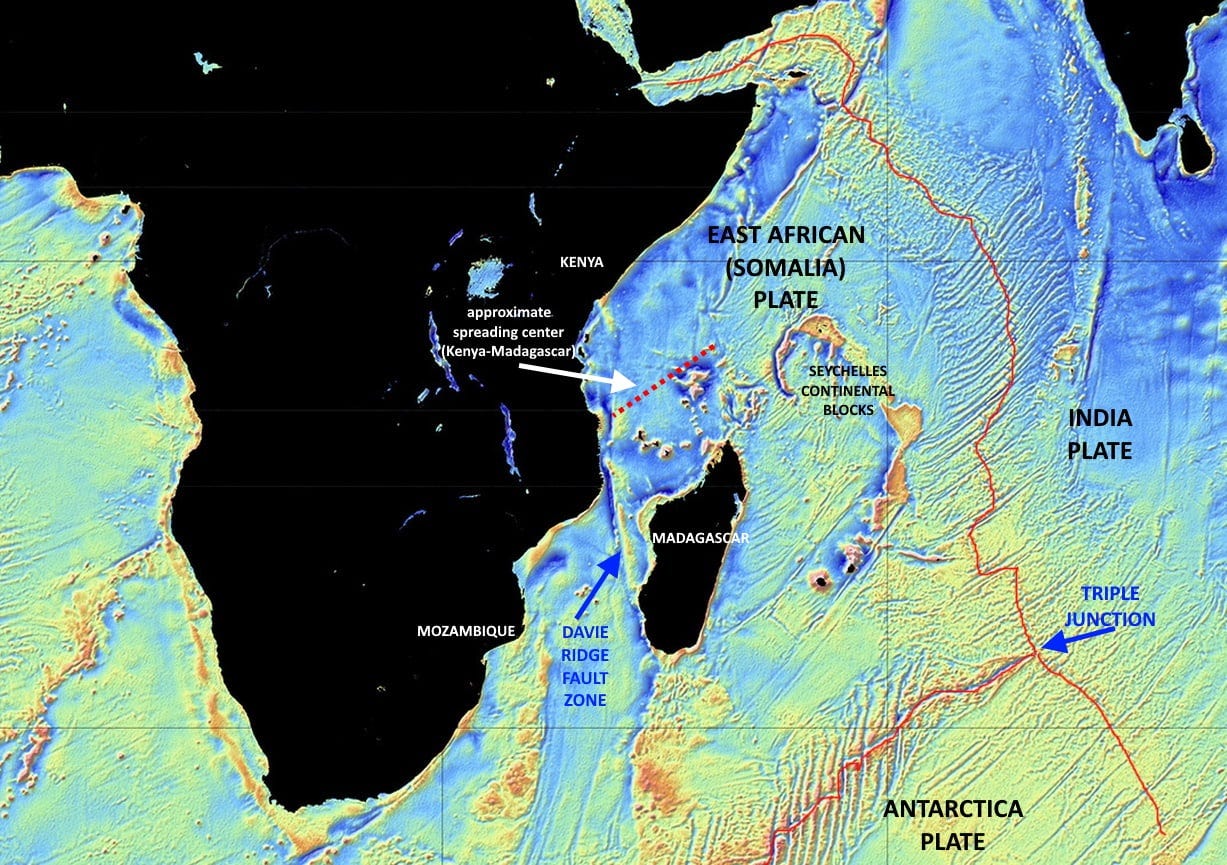

Madagascar began to move straight south (in modern coordinates) from what is now the coast of Kenya about 150 million years ago. It moved along a transform fault (like the San Andreas), sliding along a linear zone which today is entirely beneath the ocean. But it is evident in the gravity map because of denser igneous rocks that “leaked” up along that fault zone. It also created a ridge (the Davie Ridge) and both the ridge itself and the igneous rocks contribute to the long linear gravity anomaly you see on the map here (from Scripps Institution of Oceanography using data from Jason-1 and Cryosat-2 satellite-derived radar altimetry).

The break between Kenya and the northwestern coast of Madagascar is a true mid-ocean rift, with paired magnetic anomalies on either side of the axis that represent the sequential upwellings of magma along the rift. It’s not nearly as sharply defined as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, but it is still marked by present-day volcanic activity in the Comoro Islands, where at least four active volcanoes up to 2300 meters (7700 feet) high erupt every few years. Karthala, on Grande Comore Island, has erupted at least 32 times in the past 200 years, most recently in 2006.

Rifting within the conjoined Africa-Madagascar continent began in Carboniferous to Permian time, around 240 to 300 million years ago, but sea-floor spreading and the true separation of the two blocks didn’t begin until about Middle Jurassic, around 150 to 160 million years ago (Coffin & Rabinowitz, 1988, Evolution of the conjugate East African-Madagascan margins and the western Somali Basin: GSA Special Paper 226), or possibly as long ago as 180 million years.

When Madagascar began to separate from Africa, the Madagascar block was still attached to East Gondwana, comprised predominantly of the Antarctica and India-Australia Plates, so the rift represented a major breakup of the supercontinent of Gondwana. East Gondwana itself began to split up about 120 million years ago, with Antarctica+Australia and India+Madagascar starting to pull apart. It wasn’t until about 90 million years ago that India and Madagascar split, leaving a small elongate continental block between them, where the Seychelles Islands lie today. The breakup was far more complicated than the extinction of a Facebook relationship.

Although the Kenya-Madagascar rift is clearly still somewhat active (expressed by the volcanism), today Madagascar is largely locked with Africa (again) and is moving with it – or more specifically, with the East African Plate which is in the process of separating from the main part of Africa along the East African Rift System. The most active rifting in the Indian Ocean region is east of Madagascar where the complex East African Plate and the oceanic portions of the Indian and Antarctica Plates are breaking apart at a triple junction, the intersection of three oceanic spreading ridge systems (shown as red lines on the annotated gravity map).

Although Madagascar may be moving with the East African Plate, it is a distinct continental, cratonic block, separated from the continental rocks of East Africa by oceanic crust and volcanics. It qualifies readily as a “microcontinent,” one of the smaller pieces of Gondwana to rift away from the core of that supercontinent. Whether it may move more independently in the geologic future remains to be seen, but such blocks often do exactly that.

My work in this area focused mostly on the coasts of Africa and Madagascar, and especially analyzing the tectonics of the Davie Ridge. The faulting there has produced small depositional basins which are prospective for oil and natural gas.

For the mineral folks, here’s my favorite specimen from Madagascar (attributed without much confidence to Tsitondroina), a quartz crystal with actinolite inclusions: