I admit (frequently) that the proliferation of mineral names makes me a little crazy. Ah, for the good old days when black mica was just biotite…. But now, given careful chemical and structural analysis, we do understand the nature of mineral series much better, and I accept that. But it leads to crazy names like fluorotetraferriphlogopite, one of many members of the biotite group, and biotite is no longer a specific mineral per se. BUT, “biotite” still works as a field term for unanalyzed dark mica!

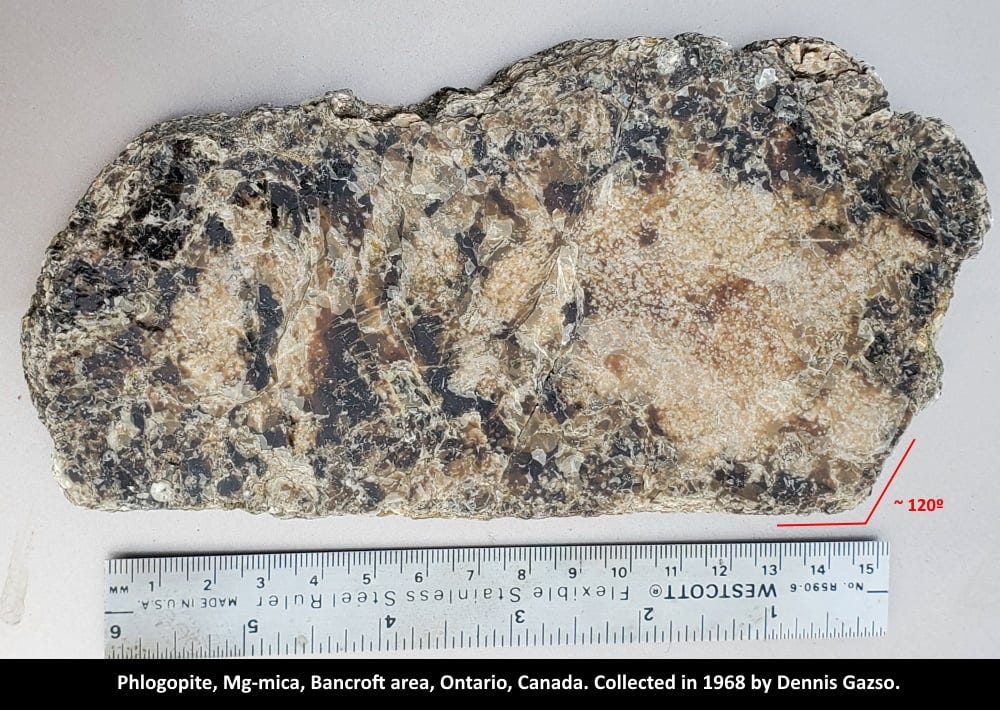

In that connection, here’s a big plate of phlogopite. I learned phlogopite as the brown mica, toward the magnesium end member in the series with biotite, which was at the iron end. The pure iron end member of the biotite group is now called annite, but let that go for now. Phlogopite at least is still a legitimately defined mineral.

This is a really big piece of phlogopite, and it even shows a couple of the side faces at 120° to each other that indicate this was part of a really big crystal. Phlogopite is crystallographically monoclinic, but it forms pseudo-hexagonal crystals with 120-degree angles; but it should also be recognized that the angle marked on the photo might represent a cleavage or twin plane rather than a crystal edge.

This specimen was collected by my friend Dennis Gazso and given to me in 1968 when we were on a Flint (Michigan) Junior College geology field trip to Bancroft, Ontario. I’m not positive, but moderately sure, that this was from the dumps of the Cardiff Fluorite-Uranium Mine. Brown mica analyzed as phlogopite is reported from that locality.

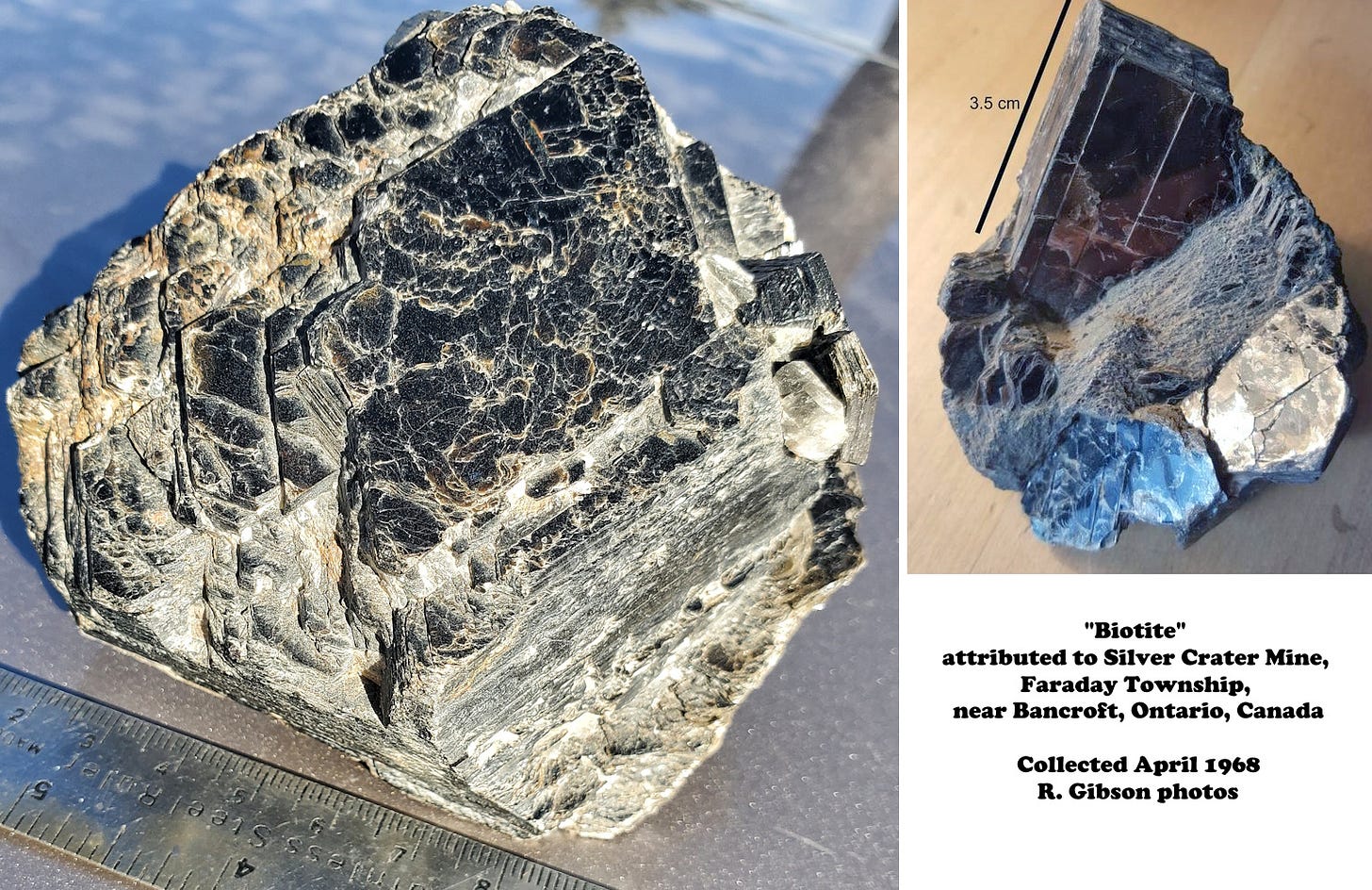

The “biotite” specimens above are attributed to Silver Crater Mine, Faraday Township, near Bancroft, where a carbonatite intruded biotite gneiss about 1050 million years ago as part of the overall Grenville Orogeny (Emproto and others, 2020, The Crystallinity of Apatite in Contact with Metamict Pyrochlore from the Silver Crater Mine, Ontario, Canada: Minerals 10, 244). Attributed because I don’t remember exactly where we went in 1968, and stupidly did not make detailed labels. It would take analysis to be certain, but this is probably close to annite, KFe(AlSi3O10)(OH)2, within the biotite group.

The Bancroft area is famous for a vast variety of minerals – at least 195 valid mineral species have been reported. They result mostly from chemical and structural complexities that developed as the long Grenville Terrane was accreted (added) to the edge of North America about 1,100-1,200 million years ago, a significant addition to the North American continent. The Grenville was by no means uniform, but it was mostly a collage of island arcs and small continental blocks. Whether those volcanic island arcs formed on or near oceanic crust (like, say, the Aleutians today) or were in a back-arc setting (analogs in the New Guinea-Fiji-Tonga region of the western Pacific today) or even within continental material (like parts of the Andes) is uncertain, but all that contributed to the chemical diversity.

The igneous intrusions included relatively unusual things like syenites (like granite, but very low in quartz), and that also contributed to the unusual mineral assemblages. Crystals the size of this phlogopite and biotite come from pegmatites, often among the last bits of magma to crystallize. Then the whole works was metamorphosed, probably more than once, which also tends to increase crystal size.

Phlogopite, KMg3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2, is from Greek words meaning “fiery looking” for the typical micaceous reflectivity on its flat sheet surfaces (and the original specimens Johann Friedrich August Breithaupt used to describe the mineral in 1841 had reddish tints). Biotite was named by J.F.L. Hausmann in 1847 for French mineralogist and physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774–1862), who was one of the first to seriously investigate micas.

Annite was named for occurrences at Rockport, Cape Ann, Essex Co., Massachusetts, USA; the cape was named for Queen Anne, mother of King Charles I of England. You may see references suggesting that the cape was named by James I of England for his wife, Anne of Denmark, but I’m quite sure it was named by their son Charles I for his mother, the same Anne of Denmark (1574-1619). I don’t know when the terminal “e” was lost. It had previously been named Cape Tragabigzanda by English Captain John Smith for a woman he met while interned in Turkey as a prisoner of war. I’m personally glad for Charles’s change to Cape Ann, because I’d be annoyed if common black mica was now called tragabigzandaite.

I enjoy your essays on minerals in your collection. I no longer collect and have donated all of my samples to the college museum where I taught for 35 years. Your essay on biotite reminded me of a sample I collected in the late 60s while working for a mineral exploration company. It has a beautiful green euhedral chlorite crystal about 2-3 centimeters wide set on a cluster of brown limonite rhombohedrons that are probably pseudomorphs after calcite or perhaps siderite. Found in an exploration pit dug into one of the many small scarns on Mt. Baldy, Little Belt Mountains, Montana. Please keep the essays coming!

This is my hometown! I live 10 minutes away from Cardiff - I got chased out of the Cardiff mine two years ago by the owner (I had been told not was owned by Faraday Township but it turns out that was NOT correct).

I have an almost identically-sized mica sample that came out of an excavation on the north shore of Eels Lake, not far from there. One of the perks of my being a builder is that I have access to new excavations and blast sites on a regular basis, you never know what will turn up here