Life in the USA is not normal. These posts have been scheduled for over a month, and they will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them.

Do you eat? Do you heat your home with natural gas or electricity? Do you ride a bike, ski, drive a car, or fly in an airplane? Do you support “green” sources of energy, such as wind and solar? Then you use and need molybdenum.

The futures price of molybdenum was over $31 per pound in early January 2023 and reached a peak of about $56/pound in March 2023, marking a rapid rise from around $18-$21 in 2022, but that was up a lot from pandemic levels of around $8 per pound in 2020. Apparently, this was driven not so much by increased demand, which remained relatively flat because of weak demand for steel (especially in China), and steel is the main use for moly. Rather the price increase was largely because of production (supply) issues: a lot of moly is produced as a byproduct of copper mining, and Codelco, the state-owned Chilean copper mining company, had lost significant production due to pandemic-related issues plus some safety and labor problems.

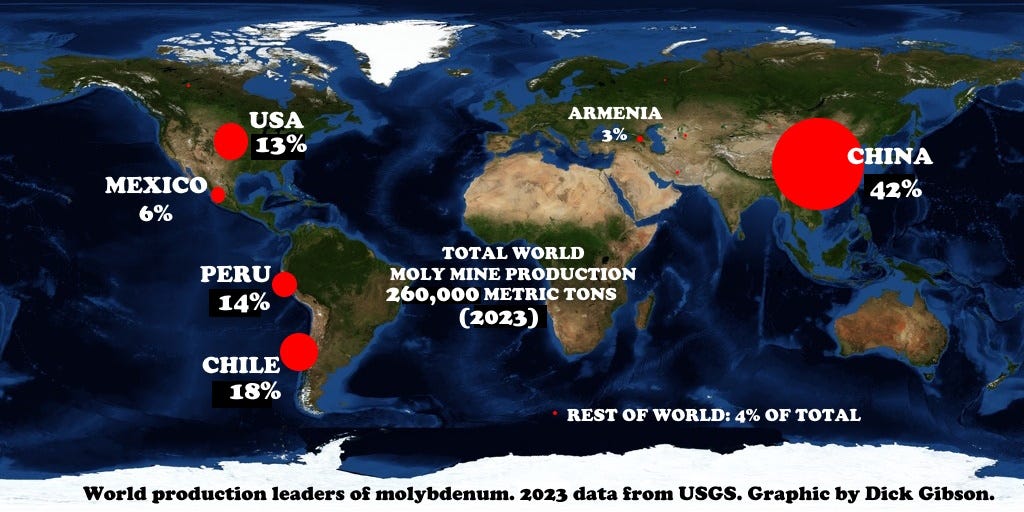

Chile is the second-largest producer of moly in the world (18%), after China (42%), and while China had been taking up the slack to a degree, China has reduced its exports because of its own domestic needs, contributing to the price increases in 2023. Peru, the #3 moly producer (14% in 2023), had also had some production problems. The futures price is also driven partly by anticipation of increased future demand for moly in steel, especially as and when China rebounds from its pandemic problems.

By January 2025, moly’s price appeared to have stabilized at about $21/pound, about the average since 2021 apart from the 4-month spike in early 2023. The takeaway from all that price info is that while occasional sharp fluctuations may occur both for real reasons and for perceptions of issues, on the whole, prices of commodities ultimately will reflect fundamental basics of supply and demand, with sometimes long-term changes related to changing consumption trends.

The #4 moly producer is the United States (13% of world production), mostly from two mines in Colorado, with seven mines (four in Arizona, and one each in Montana, Nevada, and Utah) producing moly as a copper byproduct. The temporary price increases were good news for those mines, especially since the price of copper was also rising, though not quite as dramatically as molybdenum. In early 2023 at the Montana Resources mine in Butte, moly was probably their most valuable product in terms of futures prices on the London Metal Exchange. The last I heard, Montana Resources generally produces about 0.8 pounds of moly per ton, compared to about 6 pounds of copper per ton; in January 2023, that worked out to about $26 per ton for the molybdenum and $24 for the copper.

About 88% of the moly consumed in the US goes to metallurgical uses, mostly to make steel harder, tougher, stronger, and corrosion-resistant, especially under high-temperature conditions. You can’t build a modern airplane without moly steel, which is also used in helicopter rotor blades and other aerospace products. Moly steel is in wind turbines, automobiles, bicycles, and ski lifts, and some ski wax contains molybdenum sulfide. Molybdenum is used as a substrate and electrode in solar panels. Some stainless steels contain 3% or more molybdenum, in some knives, surgical tools, and laboratory containers, but chromium is the main alloy with iron in stainless steels.

Moly is used as a catalyst in oil and natural gas refining to remove sulfur. Natural gas accounts for about 38% of electricity generation in the US, and for almost half of the home heating in the United States.

Volumetrically small but critical uses for moly include fertilizer components for commercial crop production and livestock feed, and it is also found in pigments (molybdenum orange) and lubricants, as well as in circuit board inks in computers and components in electronic devices like cell phones.

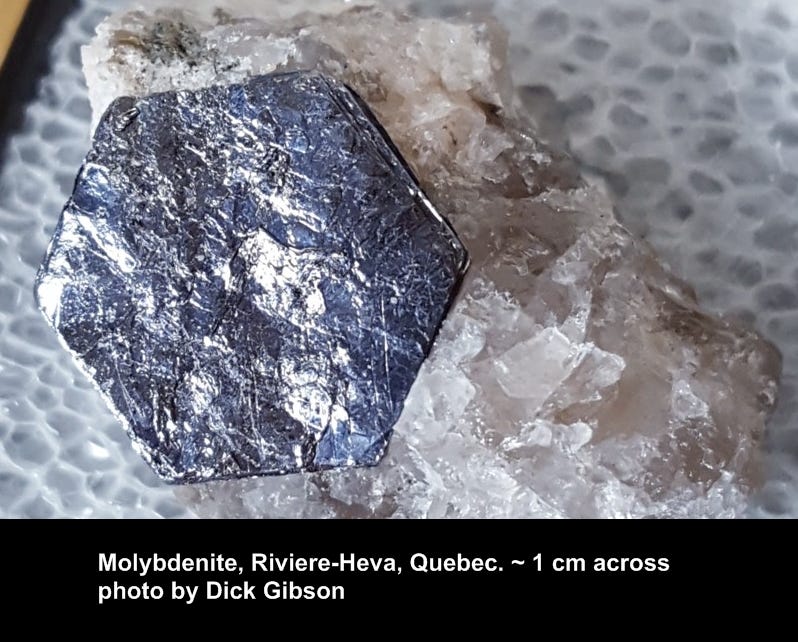

Molybdenum sulfide, molybdenite, is the only significant ore of molybdenum. It’s a soft, greasy gray mineral, much like graphite, and it usually occurs in flaky to massive bodies. Crystals are relatively unusual: I share the photo of one from Quebec.

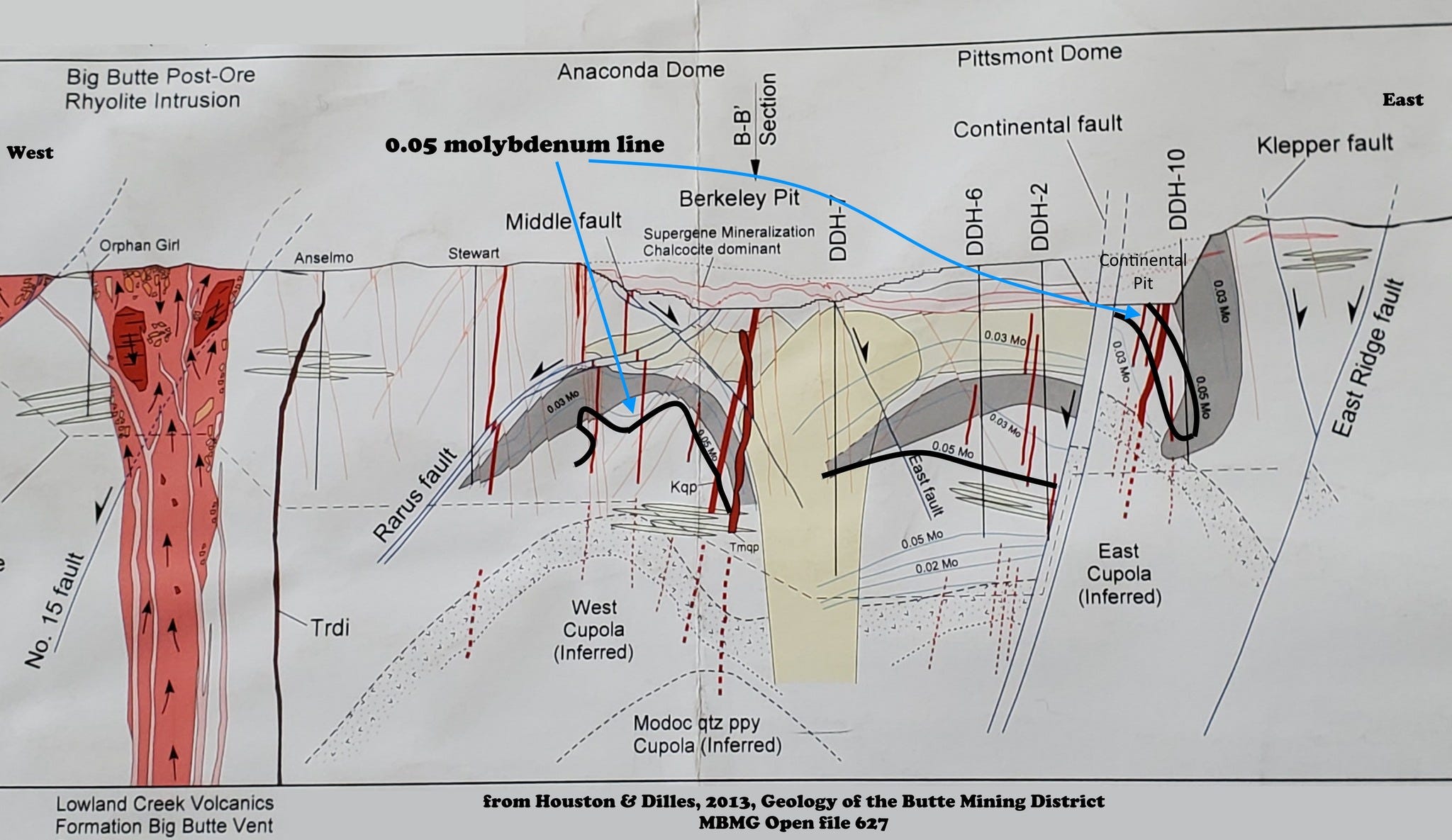

At Butte the moly zone, where there is more molybdenite than in other parts of the ore body, is about 4000 feet beneath the surface at the Berkeley Pit. But thanks to about 4000 feet of offset on the Continental Fault System east of the Berkeley Pit, the Montana Resources Continental Pit can exploit the moly zone at the surface, contributing to the value of their ore. On the cross-section above, from Houston & Dilles, I’ve emphasized the 0.05% moly zone line to show the differences in its depth across the Continental Fault Zone.

Montana Resource’s production at Butte contributes around 8% of the total US moly production of about 45,000 to 50,000 metric tons per year, which makes the US not only the #3 world producer, but also a net exporter of molybdenum – one of only a handful of mineral commodities for which that is true. Among metals, the US is a net importer of such things as copper, lead, zinc, tin, rare earths, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and many more, so having a metal to export is unusual. Even so, the global nature of mineral commodities means the US imports almost as much moly metal, ores, and concentrates as it mines: 31,000 metric tons imported vs 34,000 tons mined. The primary import sources for moly into the US are Chile, Peru, South Korea, and Mexico. In 2024 domestic consumption amounted to about 16,000 metric tons, and total US exports were about 51,000 tons, so yes, that does mean that a lot of the moly we imported was also exported. It’s complicated!

About three-quarters of US molybdenum ore and concentrates exports goes to the Netherlands, Belgium, and the U.K., which have refineries that specialize in processing metals like molybdenum.

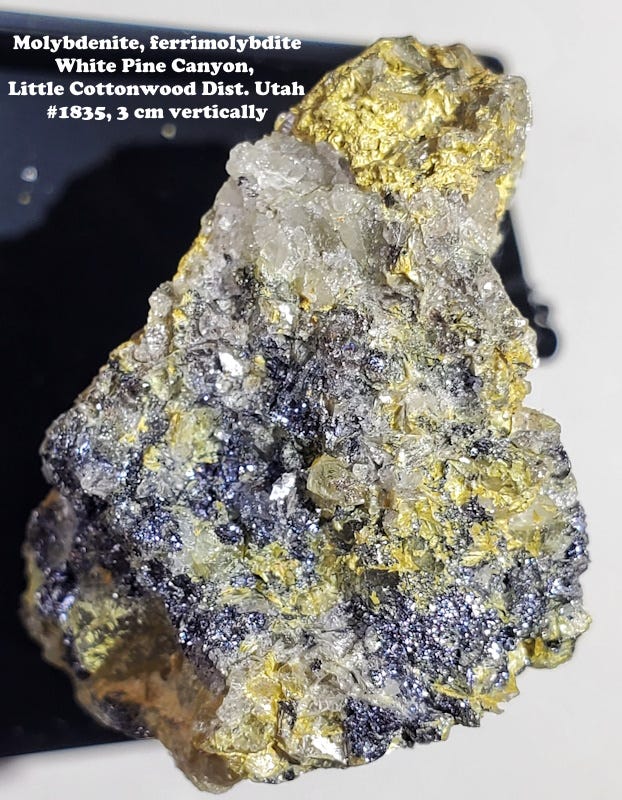

Ferrimolybdite, Fe2(MoO4)3 · nH2O, is a yellow alteration product of molybdenite.

The word molybdenum is from Greek for lead-like substances, including lead and graphite. It was proposed as a new element by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1778 and isolated as a metal by his fellow Swedish chemist Peter Hjelm in 1781. It was little used until World War I and didn’t really become important until World War II and later.