Negative crystals are spaces within crystals that contain fluid or gas – not solid inclusions – and that ideally reflect the crystallography of the crystal that encloses them.

As chemicals combine to form solid crystals, it’s common for gas or fluids (or both) to be trapped in the expanding solid framework. You can think of it as the crystal growing outward as well as inward, so crystallographically, the faces that develop on either an external side or an internal surface should be parallel. In an ideal situation, that happens, and the last remnant of uncrystallized fluid or gas would have the shape and orientation of the overall crystal.

In practice, it’s likely that crystal faces don’t grow at uniform rates, because of varying temperature, pressure, and chemical saturation conditions, as well as possible inclusions or random defects in crystal growth. Consequently sometimes the spaces inside the crystal may only have a few of the same faces as the outer form of the crystal, or none, making simply a bubble-like inclusion in the solid crystalline mass. Fluid inclusions are really common in many minerals, but most are tiny, even sub-microscopic. The examples here are small but easily visible with a simple microscope.

The photo at the top shows two negative crystals in a water-clear quartz crystal, a Herkimer “diamond,” so called for their occurrence at Herkimer, New York, USA.

Quartz is one of the commonest minerals to show large negative crystals. The example above is a string of them in a piece of quartz from McCurtain County, Oklahoma. The largest is about a half millimeter long, and only one shows most of the typical faces of a doubly-terminated dipyramidal quartz crystal.

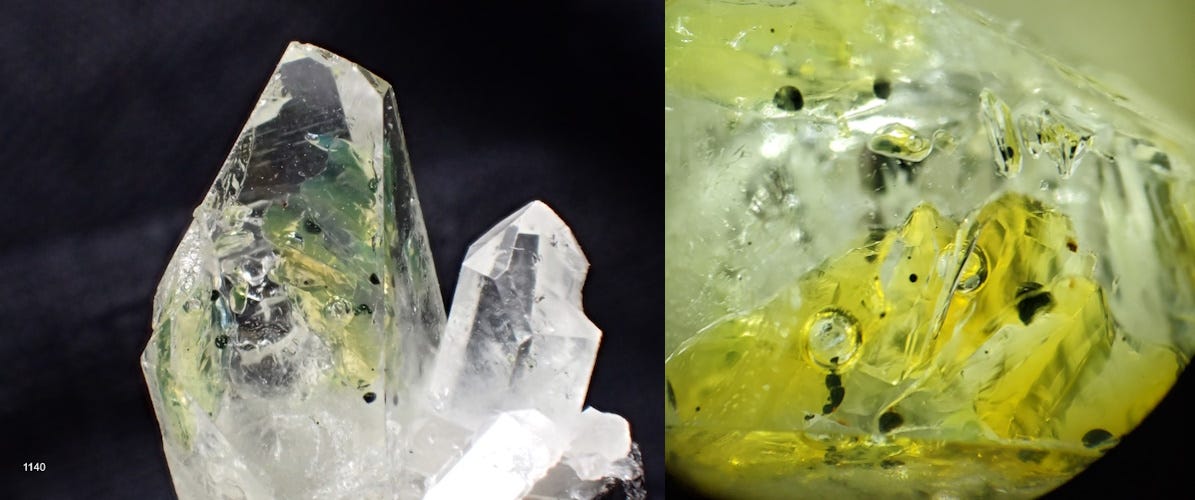

The fluid inclusions above, in quartz from Balochistan, Pakistan, barely show any crystal faces, but because the fluid is yellowish liquid petroleum, it’s easier to see them. The negative spaces also include gas bubbles and solid bitumen. The large bubble at lower left in the right-hand photo is about 1 mm across.

Because halite, common salt, sodium chloride, is easily soluble, it’s no surprise that when it crystallizes it might capture uncrystallized fluid within it. The negative crystal above crudely reflects the cubical form of halite (and some partial octahedral positions too), and also contains a movable gas bubble.

The negative crystals in this spodumene (the pink variety, kunzite) crystal from Pala, California, are the spear-like features. They are difficult to photograph, but I promise these are actually narrow, pointed open spaces that clearly began at tiny crystallographic defects, the triangular facets at top and dark spots in the lower part of the crystal in the upper image. The defects are on the surface of the large enclosing crystal, and the openings extend into the crystal. The orange-brown colors are because the negative crystals reach the surface, and traces of iron oxide have gotten into the open spaces. They are at most just over a millimeter in length.

The negative spaces are perpendicular to the elongation direction of the main crystal. Spodumene is monoclinic, and I have not determined what crystallographic position(s) the negative spaces represent, but I’m sure they are more than just “holes.” The starting points for many of them, the dirt-filled dark spots in the photo, have skewed square outlines.

This one is another Herkimer diamond, with several negative crystals inside the larger quartz crystal. The largest is about a quarter millimeter long. The irregular yellowish blob is also an internal void space. The yellowish tint is from iron oxide in a crack in the crystal. In the photo of the whole crystal, the black is inclusions of solid bitumen, called “anthraxolite”.

Thanks to a suggestion from subscriber Mike Reinke, I found some negative crystals in a fluorite specimen from Illinois, USA. In the photo above, the large negative crystal at right center is just under one millimeter in longest dimension.

My favorite negative is an Illinois fluorite with a rectangle in it with a bubble in the rectangle. Nice geometry. A micro, but worthy.

As long as negative crystals aren't meth or something like that....

Now this reminds me of the interpretation of the positron as a single missing electron in a solid sea of electrons.