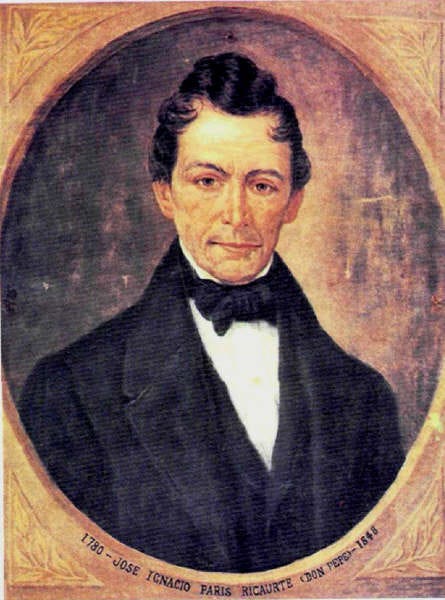

Parisite is not a mineral that sucks the life out of other minerals. It was named for José Ignacio París Ricaurte (1780-1848), proprietor of the emerald mine at Muzo, Colombia, where parisite was discovered by him in 1835.

Technically, “parisite” is a group of rare-earth calcium carbonates with fluorine, where cerium, lanthanum, or neodymium is a common essential rare-earth element, but parisite-(Ce), the cerium-based member, is far more common. Its formula is CaCe2(CO3)3F2.

The two specimens here are from the Snowbird Mine near Alberton, Montana, where parisite occurs in coarse carbonates that were mined for fluorite in 1956-1957. The coarse calcite crystals led early workers to construe the body as a carbonatite, an unusual igneous rock dominated by calcite and other carbonates that were formerly molten, but more recent work interprets the deposit to be from hydrothermal fluids associated with the Cretaceous Idaho Batholith (Samson and others, 2004, Fluid inclusion characteristics and genesis of the fluorite–parisite mineralization in the Snowbird deposit, Montana: Economic Geology, v. 99, p. 1727–1744).

The deposit is hosted in Belt Supergroup rocks around 1.4 billion years old, but the material has been dated to about 71 million years, comparable to the Idaho Batholith (Metz and others, 1985, Geology and geochemistry of the Snowbird deposit, Mineral County, Montana: Economic Geology, 80:2, p. 394–409).

The Snowbird occurrence is similar to other deposits in the Lemhi Pass area (Montana-Idaho border) that are being explored for their rare-earth potential. Carbonatites and similar rocks typically concentrate unusual elements into unusual minerals like parisite. At the Snowbird Mine, the deposit also includes uncommon nickel-arsenic minerals like gersdorffite and annabergite together with some world-class specimens of parisite.

The broken brown parisite crystal in the specimen above is about 3 cm long and is embedded in yellowish calcite, some of which is colored brown by iron oxides or other impurities.

Rare-earth elements are neither rare nor “earths”: they are metals. Cerium is actually the 25th most abundant element in the earth’s crust, more abundant than gold, silver, mercury, tin, or lead, but the atomic properties of cerium and other rare-earth elements make it unusual for them to combine with other elements and molecules to make minerals. So rare-earth mineral concentrations are fairly rare even when the elements themselves are not.

Both these specimens were collected by Chris Gammons of Montana Tech.

Painting of José Ignacio París Ricaurte by Delio Ramírez Beltrán, public domain.

Another enlightening column, Richard. (Glad to know that parisite does not feed on other minerals...)

It will set off a Geiger counter. Don’t sleep with it. I notice you didn’t include uranium in the chemical makeup.