If you’re moderately well versed in geography, you may know where the nation of Mali is, landlocked in West Africa. Maybe you know that Timbuktu is in Mali. If you’re like most people including me (although I know a few exceptions!), after that, you have a largely blank spot on your mental map. Mali covers an area just slightly less than Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon combined, or more than Spain, Portugal, and France combined.

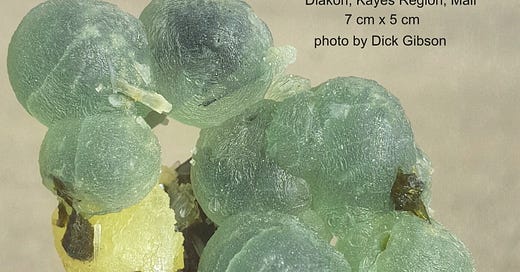

This specimen is from a fairly new (early 2000s) discovery in the Diako (Diakon) area of western Mali (Kayes Region), where these pretty green balls of prehnite associated with yellow stilbite and dark green epidote were found. Prehnite is a relatively common calcium aluminosilicate that forms in low-temperature hydrothermal settings with other minerals such as the zeolite stilbite. It can indicate either late-stage or secondary igneous or low-grade metamorphic environments. It gives its name to the prehnite-pumpellyite metamorphic grade, which represents a temperature range of 250 to 350 °C and a pressure range of approximately two to seven kilobars. Both ranges are almost as low as you can go and still call a rock metamorphic. Only the zeolite facies is lower.

The big, almost spherical balls of prehnite from Mali rapidly became highly sought-after mineral specimens.

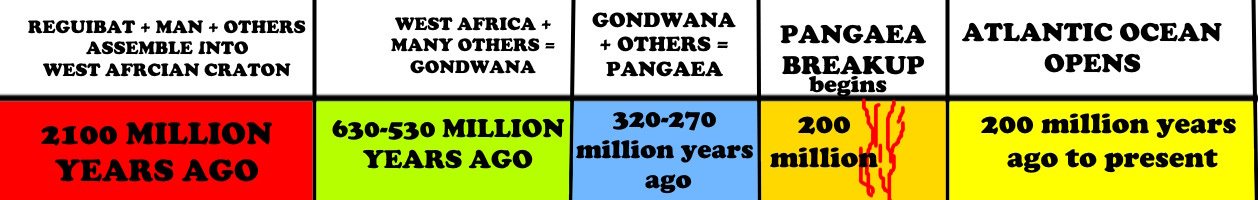

The West African Craton is a discrete terrane that extends from the Anti-Atlas Mountains in southern Morocco south to the Ivory Coast. It does not continue to the Atlantic coast in the west in most places, so most of Senegal and Mauritania are not within it. To the east, it ends in an approximately north-south line through Togo, far eastern Mali, and west-central Algeria. The West African Craton was assembled as an independent unit during Archaean and early Proterozoic time (largely in the Eburnian Orogeny about 2.07 to 2.10 billion years ago; Liégeois et al., 1991, Short-lived Eburnian orogeny in southern Mali: Precambrian Research 50: 111-136). Two areas of Archaean rock, the Reguibat Shield in northern Mauritania and the Man Shield in Guinea, Liberia, and Ivory Coast, are the exposed ancient cores of the craton (“craton,” you may recall, is from Greek for “strength”).

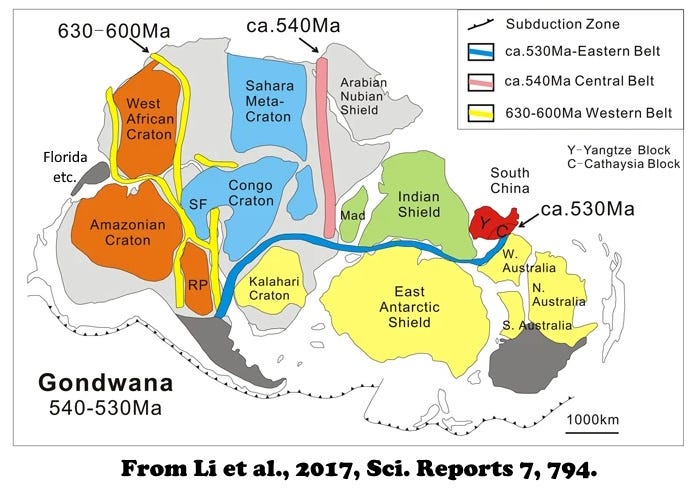

Once the West African Craton existed as an independent continental block, it could (and did) interact with other blocks. The Pan-African Orogeny (orogeny means mountain-building) was a lot more than “all-Africa” – over the hundred million years from about 630 to 530 million years ago, most of Africa, South America, India, Antarctica, and Australia, plus some smaller bits that are now in Florida and South China, came together to form the supercontinent of Gondwana (Li and others, 2017, First Direct Evidence of Pan-African Orogeny Associated with Gondwana Assembly in the Cathaysia Block of Southern China: Scientific Reports 7, 794).

Gondwana and the northern continents (Laurentia, approximately North America; Baltica, Europe; and Siberia and other pieces) combined about 335 million years ago to form Pangaea, a really super supercontinent.

Between the ancient Archaean cores of West Africa, the huge Taoudenni Sedimentary Basin covers most of Mali. It holds mostly middle to late Proterozoic and Cambrian rocks deposited early in Gondwana’s history, but in western Mali around Diako, igneous intrusive rocks (dolerite, also called diabase, a mafic rock equivalent to basalt and gabbro in composition but representing an intermediate texture) about 201 to 197 million years old (Early Jurassic) probably record the breakup of Pangaea and the resulting massive igneous activity associated with the initiation of the Atlantic Ocean rift.

The diabase in Mali is part of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP), one of the largest intrusive and extrusive (volcanic) episodes in earth history, linked to a mass extinction at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary 199 million years ago (Verati and others, 2005, The farthest record of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province into West Africa craton: Precise 40Ar/39Ar dating and geochemistry of Taoudenni basin intrusives (northern Mali): Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 235, Issues 1–2, p. 391-407).

It was probably those 200-million-year-old intrusions that provided the hydrothermal solutions that produced the prehnite mineralization at Diako. I think the minerals are in skarns in the diabase dikes and sills and in the Neoproterozoic stromatolitic carbonate rocks they intrude. “Skarn” is a rock resulting from not just metamorphism (rearranging the chemicals into new minerals using the same chemistry, “changed form”) but also metasomatism, where new chemicals are introduced so the new minerals that form can be quite different; “changed body”).

Prehnite was named in 1788 for Hendrik von Prehn, the governor of the Dutch Cape Colony, South Africa, who is credited with discovering the mineral.

Mineral specimen catalog number 1153. Acquired at the Tucson mineral show in 2017.

Sources:

West Gondwana basemap By Voudloper - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cratons_West_Gondwana.svg CC BY-SA 3.0

CAMP map from Whalen and others, 2015, Supercontinental inheritance and its influence on supercontinental breakup: The Central Atlantic Magmatic Province and the break up of Pangea: Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 16, 3532–3554 https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2015GC005885

Gondwana assembly map from Li et al., 2017, First Direct Evidence of Pan-African Orogeny Associated with Gondwana Assembly in the Cathaysia Block of Southern China: Sci. Reports 7, 794.

Shared to LinkedIn Richard. Keep up the good work!