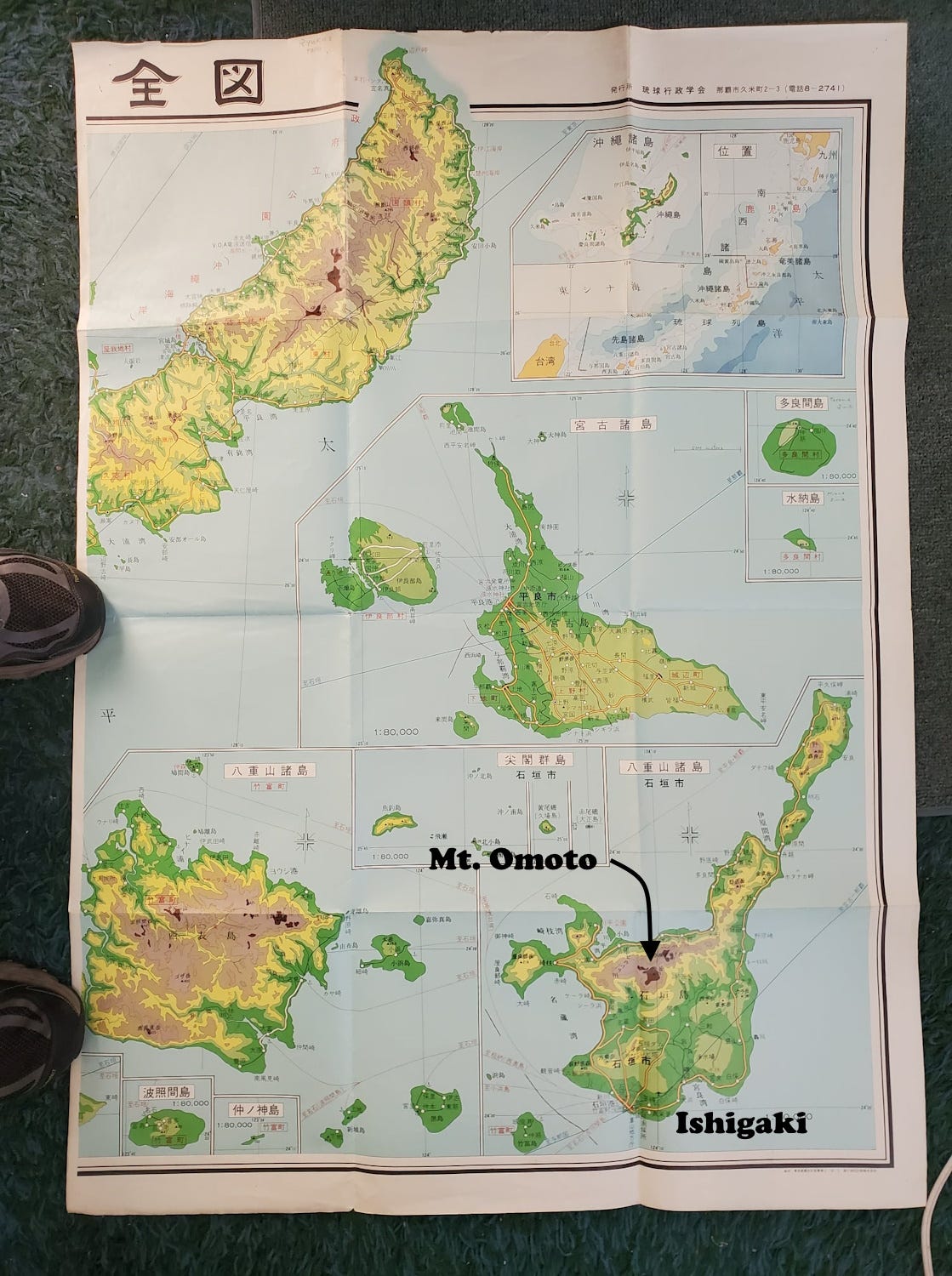

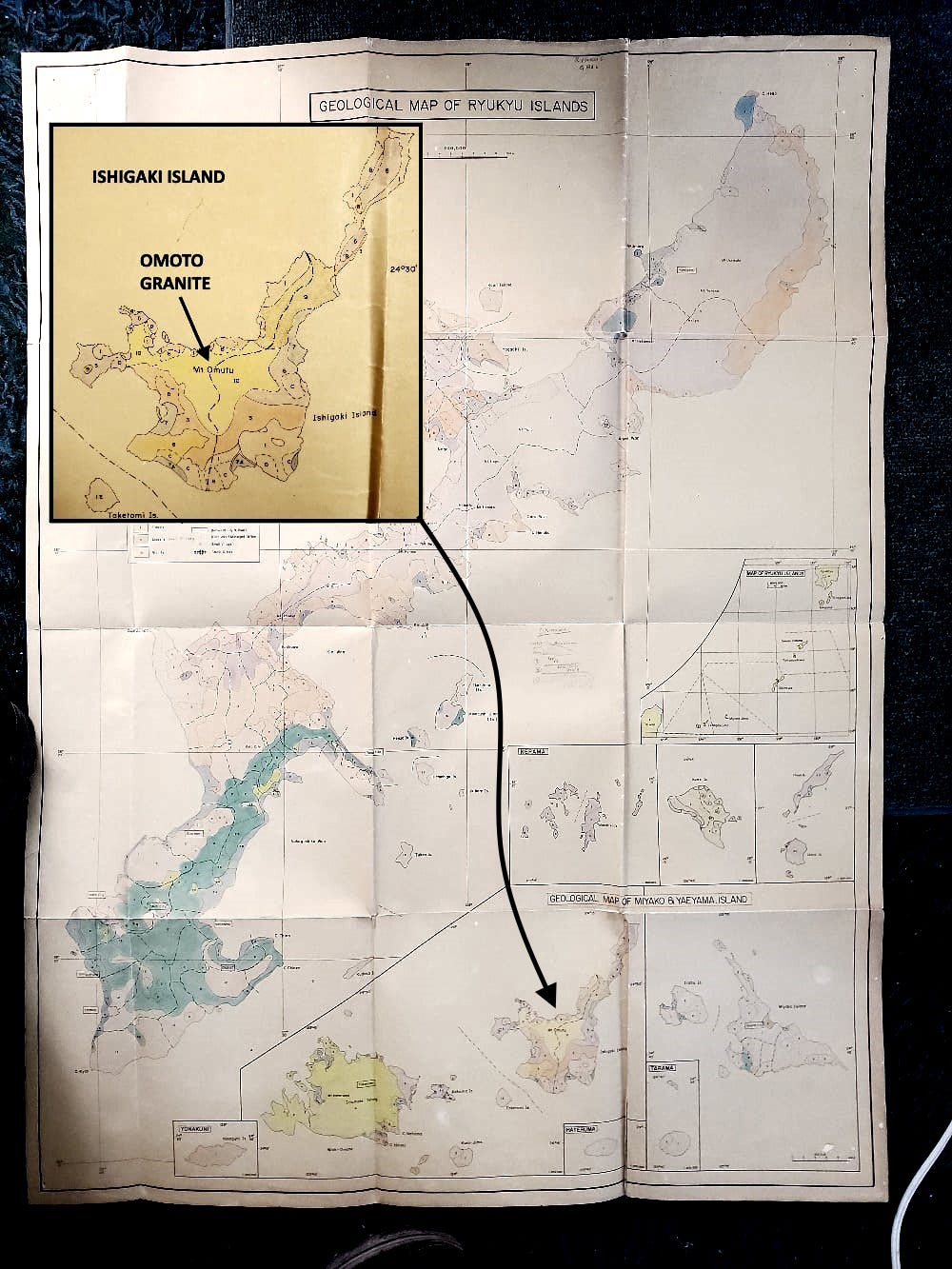

Show of hands, how many have a vintage giant size topographic map of the Ryukyu Islands (OK, only half of the map shows in the photo above) in Japanese, AND a hand-colored geologic map of the same area?

I like maps and I like languages, and these maps cost 10 cents each back in the mid-1990s, so I obviously HAD to have them. Nothing about need, it was about having.

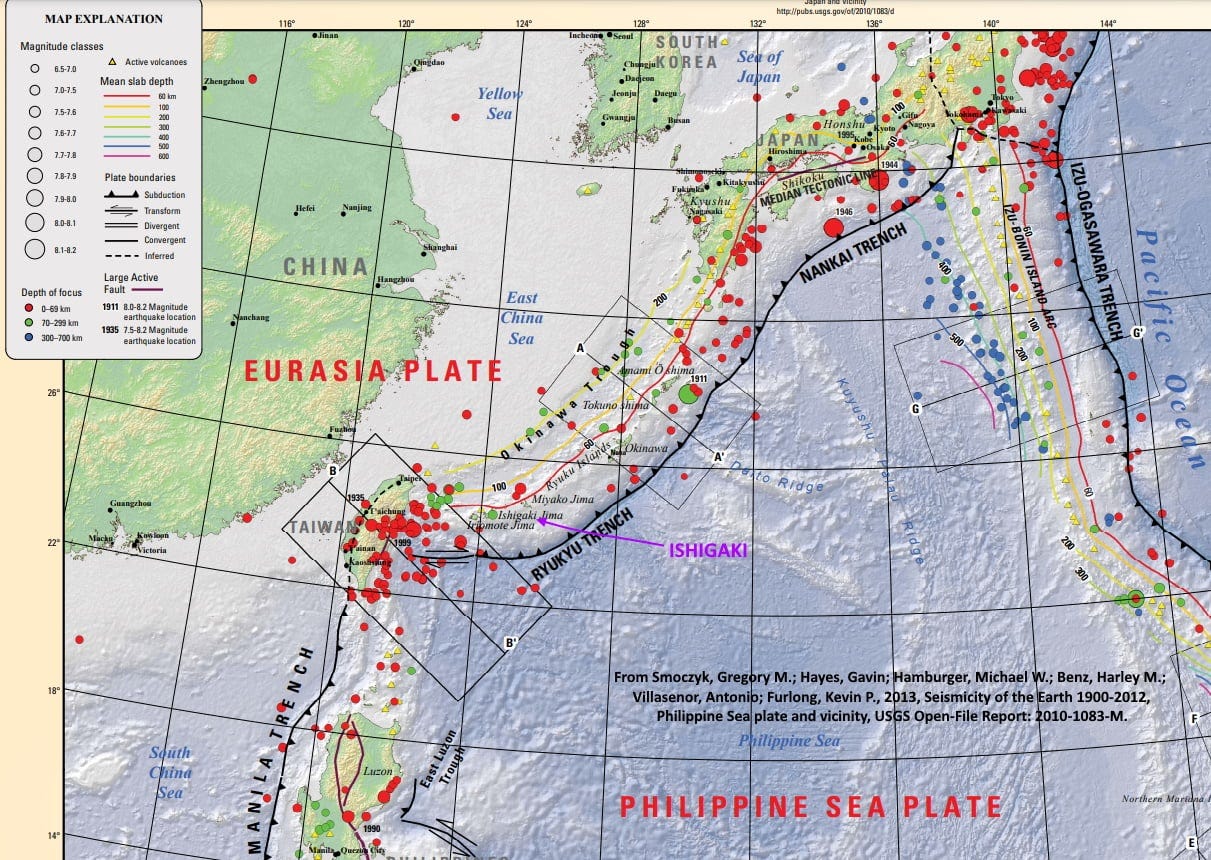

The Ryukyu Island Arc with Okinawa its largest island is a straightforward tectonic feature. It’s an arcuate row of volcanoes above the subduction zone where the Philippine Sea Plate (mostly oceanic) is pushing northwestward and subducting beneath the edge of Eurasia, which there is under water, the East China Sea, but which is mostly continental in nature.

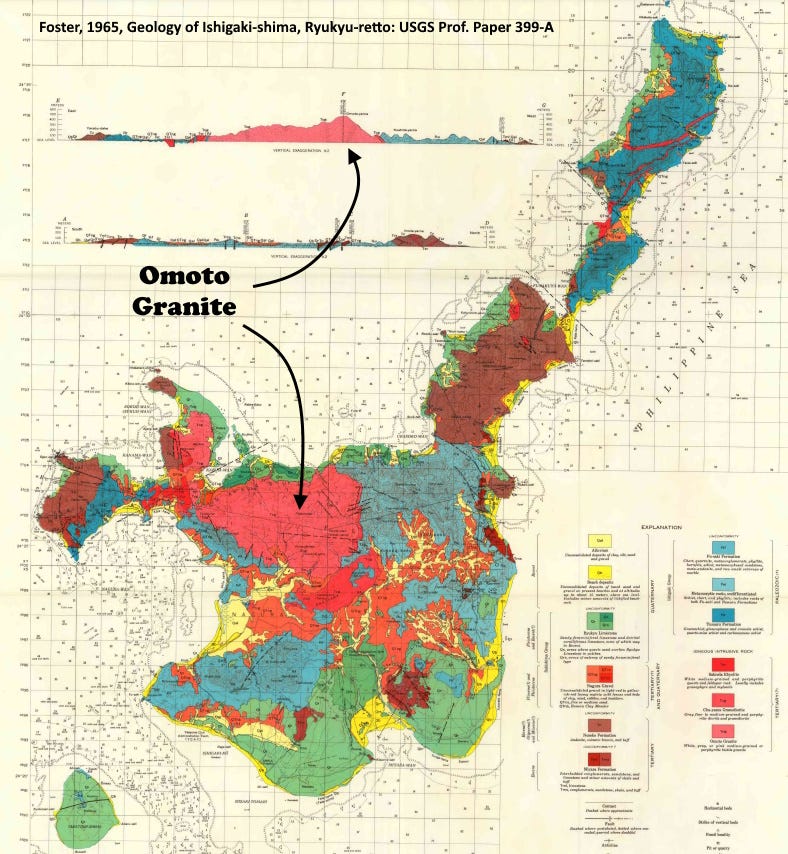

Subduction usually makes for intrusive and extrusive volcanic rocks of intermediate composition (andesite), a mixing of basaltic oceanic crust and less mafic (magnesium, iron) sediments in and around trenches associated with subduction. Granitic rocks are more typical of wholly continental settings. So it was a little surprising to see an area mapped as “granite” on Ishigaki Island, one of the Ryukyu chain in the southwestern section of the arc.

But not that surprising. First, even though the Ryukyu Arc is 450 to 700 km away from the coast of China, it’s not far from the edge of the continental shelf. There is a bathymetric low west of the Arc, called the Okinawa Trough, which is a classic back-arc basin, a down-faulted extensional zone on the edge of the continental crust above the down-going subducting oceanic crust, which is doing that because of compression. Yes, you can (sometimes almost must) have compression and extension simultaneously in very close proximity.

Second, the entire Japan-Ryukyu subduction zone and arc are quite mature, so the opportunity for more and more mixing of rocks, to evolve to granite, is more likely. Subduction at Japan has been going on for at least 35 million years and possibly as long as 60 million years. At Okinawa and Ishigaki, it’s at least 15 and probably more than 25 million years of continual subduction. That means that some of the “original” (or at least early-formed) andesitic, intermediate volcanic rocks probably get subducted themselves, along with more of the sediments and water lying on top of them.

When you melt, or partially melt such material, it can differentiate into magma that’s much less mafic (less iron-rich, less like oceanic crust), and indeed you can make granitic melts. Alternatively, Ishigaki might be close enough to the continental margin for some actual continental material to be incorporated and melted in the subduction process.

Specifically, the Omoto Granite on Ishigaki is an I-type granite, derived from melting or partial melting and homogenization of primarily igneous rocks (hence the “I”). This contrasts with S-type granites, which derive from supracrustal rocks, which is to say mostly sedimentary materials that have undergone a lot of weathering and therefore aluminum and silica enrichment. That enrichment is one of the hallmarks defining the differences between I- and S-type granites, but there is a whole set of geochemical differences. See also Sawaki and others, 2024, Zircon Trace‐Element Compositions in Cenozoic Granitoids in Japan: Revised Discrimination Diagrams for Zircons in I‐Type, S‐Type, and A‐Type Granites: Island Arc 33:1.

The Omoto Granite is at least 21 million years old and possibly closer to 38 million, so clearly there’s been an oceanic-continental interaction here for a long time. See, for example, Foster, 1965, Geology of Ishigaki-shima, Ryukyu-retto: USGS Prof. Paper 399-A; and Daishi and others, 1986, Fission track ages of some Cenozoic acidic intrusive rocks from Ryukyu Island: The Journal of the Japanese Association of Mineralogists, Petrologists and Economic Geologists 81(8), 324-332.

So next time you encounter a granite in a volcanic island arc, be intrigued, but not TOO surprised.

It’s difficult to determine the exact vintage of these maps, but both are certainly post-World War II. The topo map shows the Voice of America transmitter station, so that narrows it down to 1953 to 1972 (and more likely 1961 to 1972; the V.O.A. station was abandoned after Okinawa was returned to Japan May 15, 1972). The geologic map is a faded hand-colored blueprint from an original that was drafted with a Leroy lettering set and probably a hand-held inkwell pen. It probably pre-dates the USGS Professional Paper (399A) on Ishigaki that was published in 1965. Helen Foster’s colorful map of Ishigaki is below.