Silver

Wires

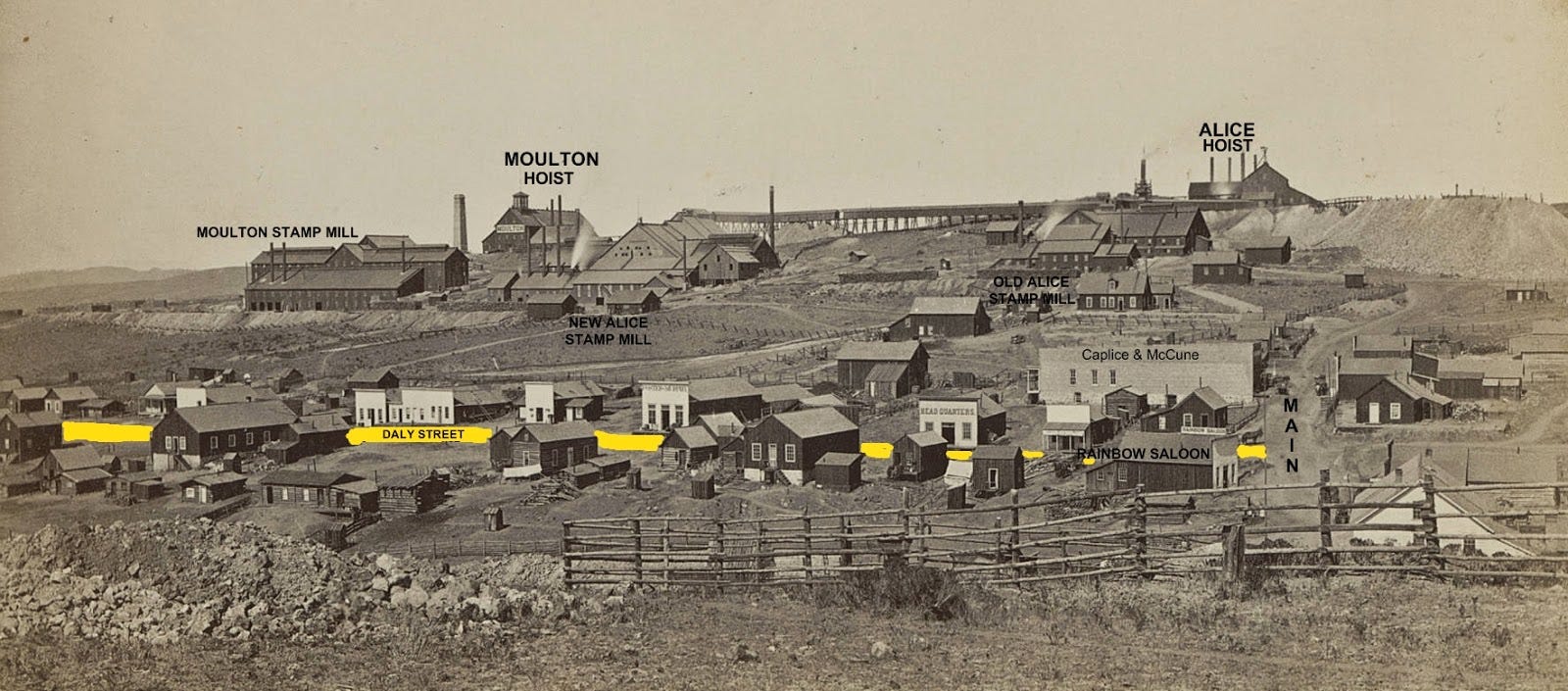

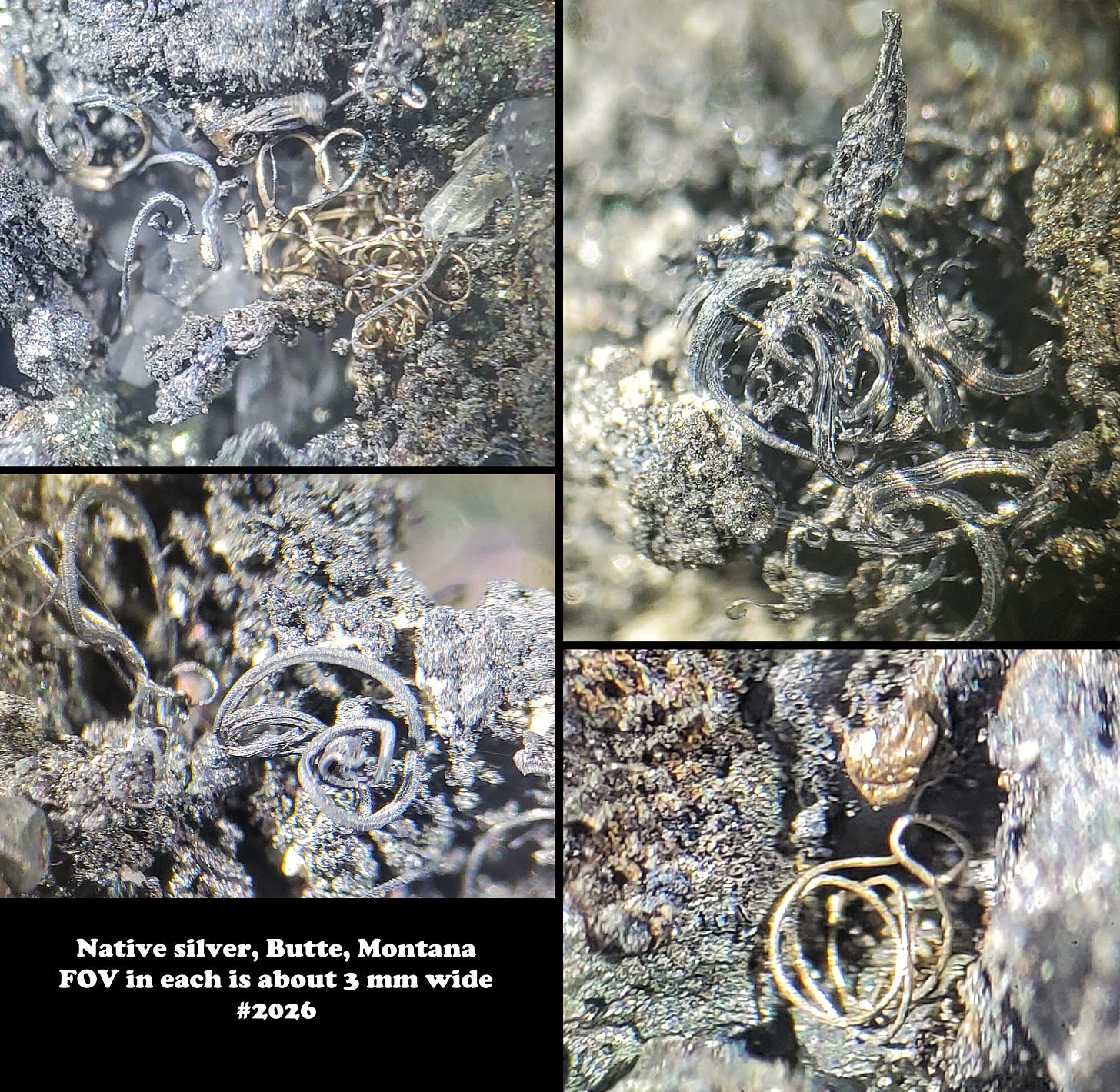

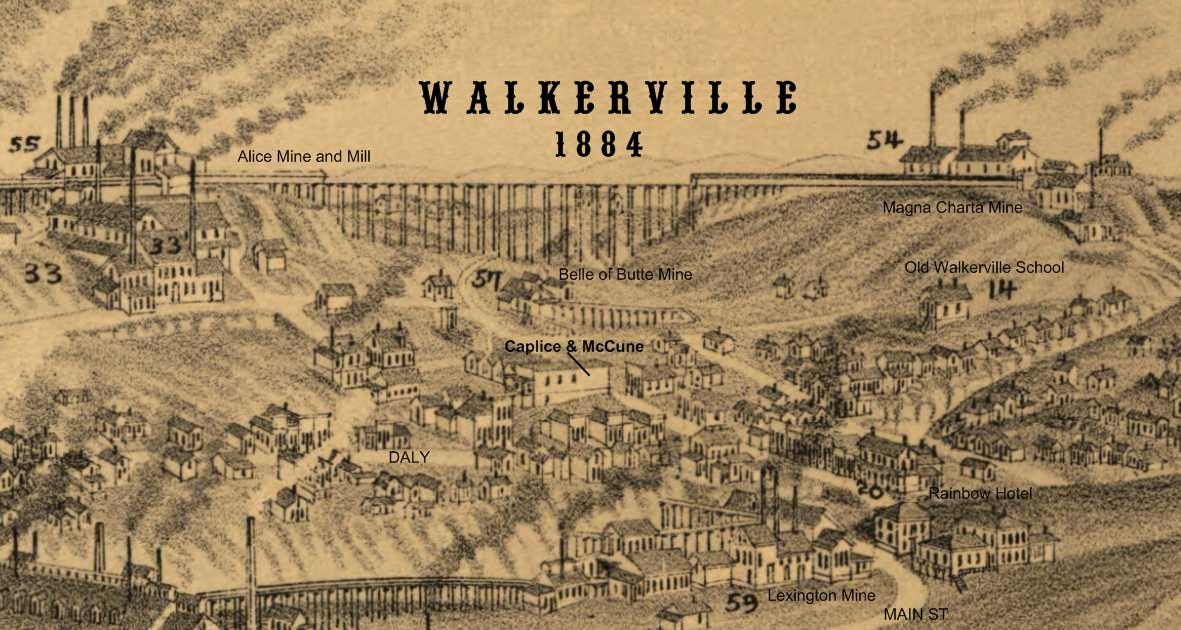

This little curve of wire silver (a dragon with a cobra in its mouth?) is from the Alice-Lexington tunnel, T400 level, Walkerville to Butte, Montana. Although Butte’s first good silver ore came from the Travona mine (renamed from the Asteroid claim) in the southwestern part of the district in 1875, touching off Butte’s rejuvenation, it was the rich silver in Walkerville and adjacent areas north of Butte that really got things going again. The Alice gave Marcus Daly both Butte experience and, when he sold his interest, finances adequate to buy the Anaconda Mine and develop it with partner financing.

The Alice and other nearby mines in Walkerville exploited the Rainbow vein system. By 1952, when the Alice-Lexington tunnel was completed, the area was mostly being mined for zinc, and the tunnel was made to haul the ores from the Alice to the Lexington which had more complete interconnections with the rest of Anaconda’s mining operations. From about 1958 to 1960 the area around the Alice Mine was excavated as the small Alice Pit. In the late 1990s the Alice Pit was stabilized and its dump relandscaped into a park. So this 5-mm piece may have been collected between 1952 and 1958, but the entire tunnel wasn’t taken out by the Alice Pit, and parts of it were accessed in the late 1980s during the New Butte Mining operation, so it could be from that time. I’ve only had it since 2017.

With about 750,000,000 ounces produced (and an equivalent amount estimated to remain unmined) Butte is probably the third largest historic producer of silver in the world, after Potosi, Bolivia, and Kellogg-Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, which is multiple individual districts.

From 2019 to 2023 the United States was between 80% and 68% dependent on imports for silver, mostly from Mexico (the world leader with about a quarter of the total production), Canada, and Peru (number 2 in the world). US silver production is less than 4% of the world total, but recycling accounts for about 16% of total US consumption.

The United States consumes more than 6,000 metric tons of silver each year, with about 34% going to investment silver (as bars). Among industrial uses, silver is consumed mostly in the electronic industry (27% of total consumption) and coinage and medals use a further 13%. Solar panels and other photovoltaic cells use 10%, and jewelry and silverware account for about 6% of US silver consumption. Historically significant amounts of silver were used in photographic processing, but that use has declined a lot because of the advent of digital photography.

Native silver sometimes makes nice cubic crystals as well as branching, arborescent growths, but it may be most famous (in a crystal habit sense) for its tendency to form complex curving shapes – hairs, curls, masses like knotted ropes or a ball of worms, all collectively called wire silver. Even though wire silver has been known since antiquity, the way wire silver forms is not fully understood (at least not by me).

Boellinghaus and others (2018, Microstructural insights into natural silver wires: Scientific Reports volume 8, article number: 9053) suggest that the elongation is a result of complex twinning of crystals that have a length-to-width ratio of 20 or more. I infer that that means a very long crystal would establish a contact twin (two crystals that share one face, the contact twin plane) on a crystal face near its tip with the similar face near the base of the next crystal. These crystals would be extremely small, around 50 µm (a micron, µm, is a millionth of a meter, or a thousandth of a millimeter).

What makes crystals form twins? The cop-out answer is the usual suspects: concentrations of the elements in the crystallizing solution, temperatures and pressures, existence (or not) of a stress regime, presence or absence of impurities. The wire silvers that Boellinghaus and others analyzed were quite pure, 99.7% silver, with traces of S, Cu, Co, Bi, Mn, Ni and Zn in most of the 20 specimens they looked at. I think they imply that impurities were not a factor in the wire growths.

It seems that the geometry of the twins might essentially drive the elongate crystals to align in a way that is offset just enough to produce a twist, a screw, in the overall structure, which leads to the curls that are a common aspect of wire silvers, although some look like uniform smooth wires, curving only because of the length of the wire or space constraints. I’ve seen photos of individual wires 10 cm or more long.

Terry Wallace, a mineralogist and geophysicist (and former director of Los Alamos National Laboratory) indicated in a Facebook post that the “why” part of wire silver development depends on temperatures that allow for mobile silver ions, preventing them from combining with sulfur. Their mobility seems to exploit the powerful electrical conductivity properties of silver (the highest of any metal), so preferential growth might be taking place in the direction of current flow (bringing silver ion after silver ion to the growing ‘tip’ of solid silver), resulting in elongate (wire) geometry.

All of that makes sense to me, although it seems that the actual molecular behavior that results in wires might be even more complex, a result of multiple variables besides those I mentioned above. But it makes for cool forms.

The four specimens above are from Butte, mined during the New Butte Mining projects of the late 1980s. They worked especially in the Lexington Tunnel (the 400-foot level of the Lexington Mine, which intersects the surface at the Syndicate Pit north of the Anselmo) and the Alice-Lexington Tunnel. That’s in the intermediate to outer zone of the Butte deposit, which contained and contains a lot of silver. They are from the Bill Stanford collection via Paul Senn.

The "silvery" wires are essentially pure silver. Those which are black have altered to a tarnish on the surface, silver sulfide, just like silverware turns black over time.

It’s well known that Walkerville was named for brothers Samuel (Sharp), Joseph (Rob), David (Fred), and Matthew Walker, Salt Lake City bankers and investors who were excommunicated from the Mormon Church. They brought Marcus Daly to Butte to manage the rich silver mines along the Alice Vein.

Less well known is that the area along the Alice Vein had been known for a few years as Rainbow – for the Rainbow lode, from which the Alice Vein branched. Professor John E. Clayton, in company with one of the Walkers, recognized the Rainbow lode in 1876 as Butte’s silver rush was taking off, and chose the site for the Alice Mine shaft. The silver-bearing outcrop they found described a sweeping, rainbow-like curve across the brow of the hillside.

The Rainbow-Alice vein system probably produced most of the district’s free-milling silver in the early years. Rich claims including the Alice, Magna Charta, Valdemere, and Moulton were all on the Rainbow lode, and made the Walker Brothers rich while giving Marcus Daly enough money and knowledge of the Butte District to personally invest in the Anaconda Mine. Daly had worked for the Walkers at Ophir, Utah, and when the Alice reached a depth of 200 feet, a 20-stamp mill was brought to the mine from Ophir, but success was such that within three years a new 60-stamp mill was built.

By 1877 Walkerville’s population was several hundred people, and the town was ready to have a post office. It had to have a name. Apparently the name “Walkerville” didn’t sit well with some residents, and a formal request by the “young women of the community” asked that the town be named Rainbow.

News reports of the day, clearly tongue-in-cheek, said “We thought Walkerville would be the most appropriate name for their village from the astonishing amount of walking in that direction that had for some time previously been done by the young gentlemen of Butte.” In fact, the writer acknowledged the young women who wanted the name change by suggesting that “it must rain beaux out there,” so give it the name Rainbeau.

Despite all this, when the post office was established in 1878, the town was named Walkerville. The Rainbow lode survived in name to the present day and the Rainbow Hotel, run by E.D. Sullivan, was on Main Street a bit north of the Lexington Mine in the late 1880s. The Rainbow Saloon stood on Main just below Daly Street.

For what it’s worth, you can also find me on BlueSky, where about all I do is Mineral Monday and Friday Fold and occasional other things.

Those organic-looking strands of 'wire' silver make me think of geomicrobes! In the field of geomicrobiology they're finding evidence of a whole biome of geomicrobes (specifically endoliths living within pores of rock down as far as a couple miles below the surface) that are respiring and living on (and thereby altering) compounds and elements other than oxygen and organic carbon. Some of them concentrate or precipitate mineral deposits, might even be responsible for the deposition of gold in hydrothermal vein deposits. I've read estimates of up to 10% or more of Earth's biomass being endolithic microbes, deeply subsurface, and they're all metabolizing down there! Slowly, of course, but maybe for billions of years - they might even have been the earliest life forms. They're only just starting to be recognized as part of Earth's bio-geological cycles.

Did not know Butte produced so much silver. My father worked for about one week down in a Butte mine during the continuing desperation for work between 1940 and end of '41. I think he was ashamed that he just couldn't take it, never talked about it, but I have a fascination for mining and Butte history.