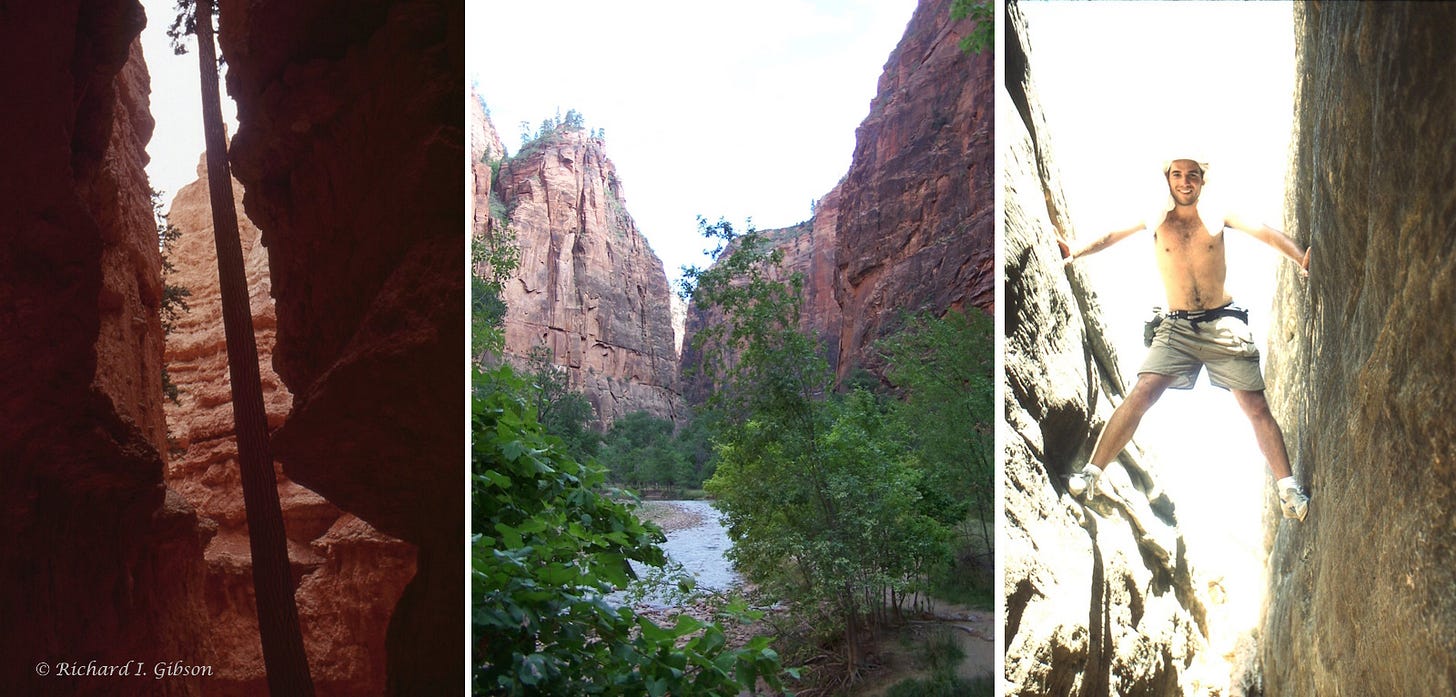

A slot canyon is one that is very narrow compared to its height, typically with a ratio of at least 1:10 but sometimes as great as 1:100. They are abundant in Utah and other parts of the Colorado Plateau, and my photos here are from the Grand Canyon, Bryce, Zion, and Canyonlands.

Slot canyons develop in erodible rocks like poorly cemented sandstone or limestone. They can start from a random low area that focuses runoff from storms, and in arid country, the erosive power of rainfall in flash floods can be intense. Once the drainage position is established, it can become a self-fulfilling zone of downcutting erosion. It’s possible that the vagaries of cementation might help guide the positions of the downcutting, but other features in the rock like fractures and joints – cracks that form because of regional stresses (and stress release) – probably provide the greatest predisposition toward focusing runoff to create slot canyons. You can see such fractures in the Google Earth image below, from Canyonlands National Park, Utah, near Druid Arch.

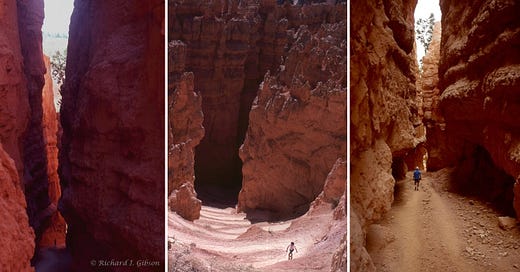

The spectacular slot canyons at Bryce are cut into the Claron Formation of Eocene-Oligocene age, about 30 to 40 million years old. It’s a poorly consolidated suite of both limestones and sandstones that were deposited in lakes and streams. Its colors, many shades of pink to orange to red, come from traces of iron oxides and hydroxides in the sediments. Iron is by far the primary coloring agent in rocks. I think all the Bryce photos are from the Navajo Loop Trail below Sunset Point, which I hiked in 1979 and again in 1997.

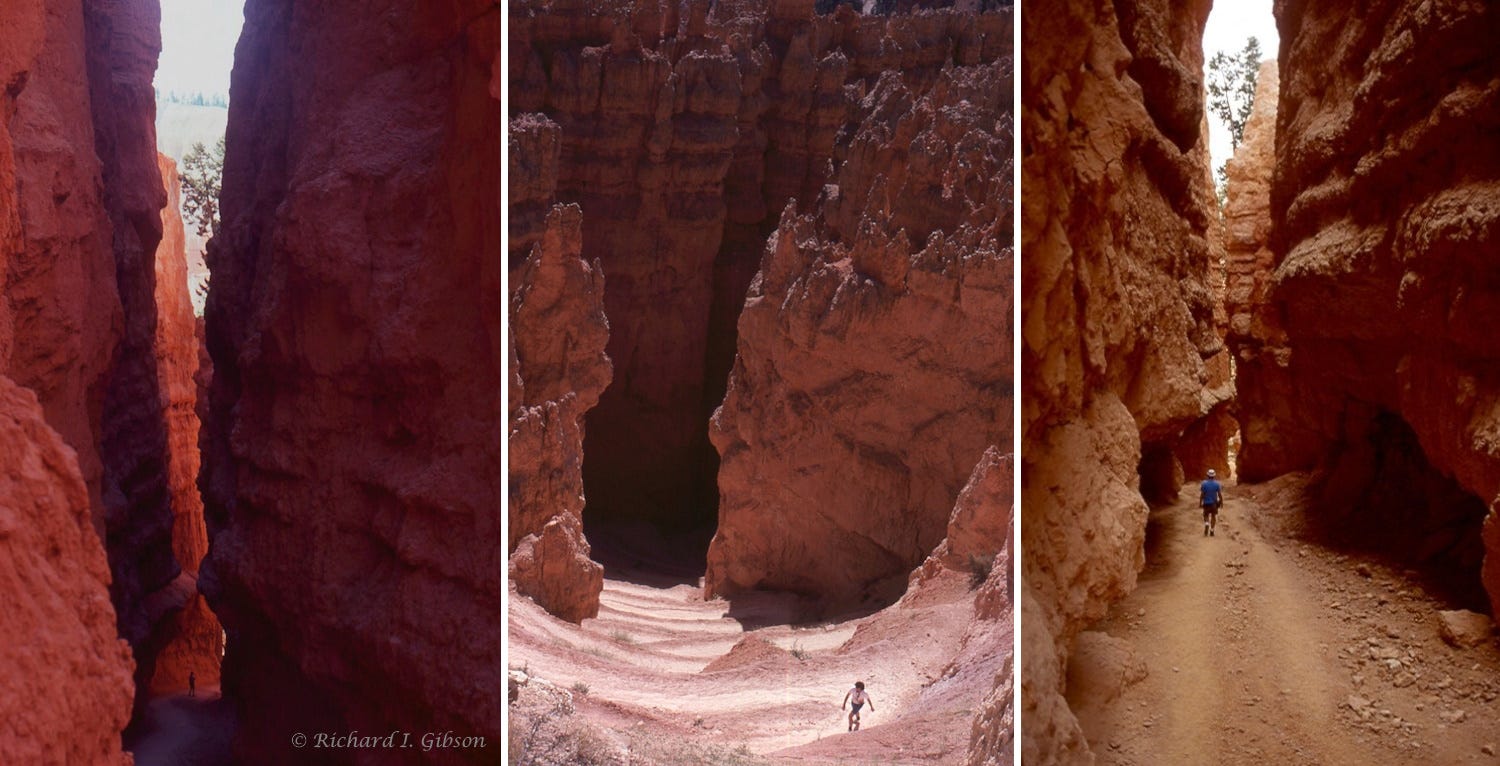

The Grand Canyon photos above are from 1986 and 1987. I think these canyons are all in the Mississippian Redwall Limestone, which is a typical gray limestone stained red by erosion of overlying red shales. In these side canyons tributary to the Colorado River, scour from the occasional floods has removed some of the surficial red stain. Ongoing continual water flow also contributes to the erosion, but much more material is removed in strong flash floods.

Apart from favorable positions related to joints in the rock, it could just be random chance that determines where a canyon might develop, especially if the rock involved is homogeneous, without significant variability. In any case, it is episodic water erosion that makes the canyon form and does the main sculpturing, but wind can modify the rocks somewhat.

The erosive power of flash floods can be huge, and in arid country like much of the Colorado Plateau most erosion takes place then, in short, ephemeral, and not necessarily frequent events. So despite the intensity of flash floods, the cutting of most slot canyons probably takes many tens of thousands of years, or even a few millions of years. But some might be cut in just a few strong flood events, in a few tens of years or so. The actual time it takes is somewhat debated because this is difficult to quantify; one anomalously strong flash flood might possibly erode several meters of rock in a day, while multiple smaller floods might cut several centimeters at a time but could add up to a lot over a few centuries. It obviously depends on the energy and volume of the water as well as the cementation of the rock.

Erosion is powerful, even (or especially) when it takes its time.

Love the phrase ' vagaries of cementation'.

And I appreciate the explanation of the red granite stained from slate. I was in the Grand Canyon about 35 years ago and on Tanner trail, in a 'micro canyon' we wandered into along the way, one wall of it was red and the other blue. A very cool effect, I had no idea then how it did that. More vagaries....

I loved Canyonlands - but also have a slot canyon in Permian red desert sandstone 1/2 mile from my house here in Nithsdale, Scotland.