Fluorescence is a property of some materials that absorb light or other electromagnetic radiation of one wavelength and emit electromagnetic radiation at a different wavelength (i.e., a different color). The most familiar example is things that are exposed to ultraviolet light which then emit light in the visible spectrum.

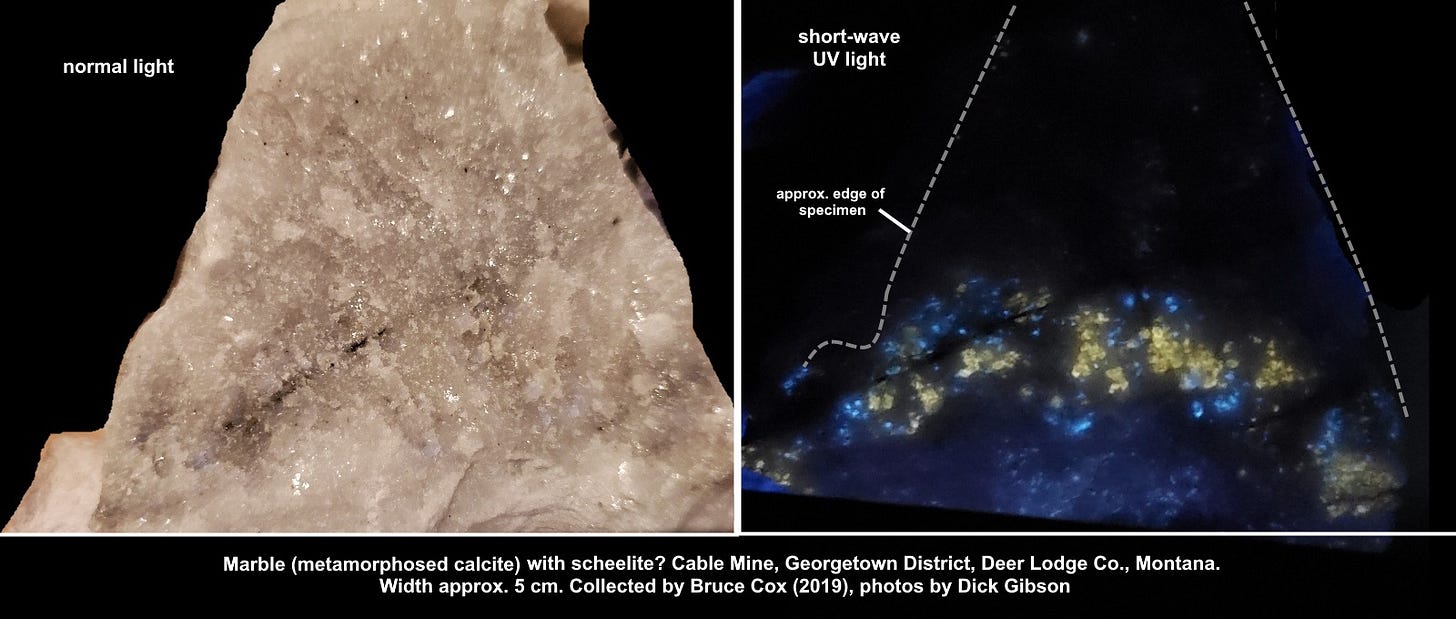

This chunk of white to gray marble shows beautiful fluorescence. Bruce Cox, who collected it at the Discovery Cut, Cable Mine, Deer Lodge County, Montana USA, and I agree that the colorful spots of fluorescence are probably caused by blebs of scheelite, calcium tungstate, Ca(WO4), in the marble. Scheelite is unusual in typically being intrinsically fluorescent, meaning the pure mineral fluoresces because of the inherent nature of its molecular geometry, rather than because of some impurity or imperfection in the mineral, which is a common cause of fluorescence. Scheelite typically fluoresces the intense blue-white color you see here in shortwave ultraviolet light.

A series extends between scheelite, calcium tungstate, and powellite, calcium molybdate, Ca(MoO4), and impurities of molybdenum in scheelite are common. And just a few percent of molybdenum can change scheelite’s fluorescence to a creamy yellow, also as you see here. Powellite often fluoresces yellow, so in the absence of analysis, we’re moderately confident that this marble contains scheelite and powellite, or at least both relatively pure scheelite and scheelite with moly impurities.

In normal light, the inferred scheelite/powellite is white and has an appearance that’s visually almost the same as the calcite in the marble that surrounds it, so it’s challenging to identify visually in normal light. It’s possible (but I think unlikely) that there is no scheelite present at all, and that the fluorescing spots are just bits of calcite with some impurities that activate the fluorescent effect.

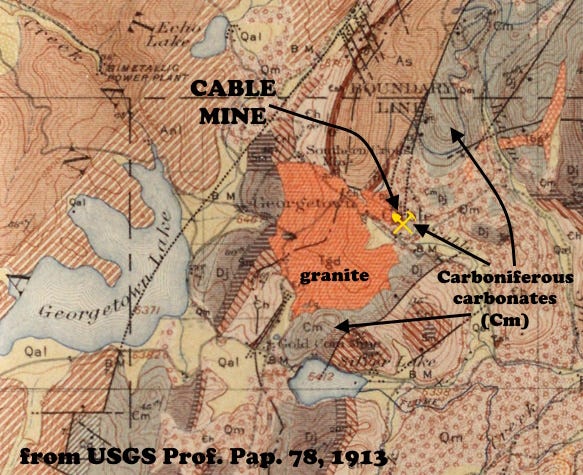

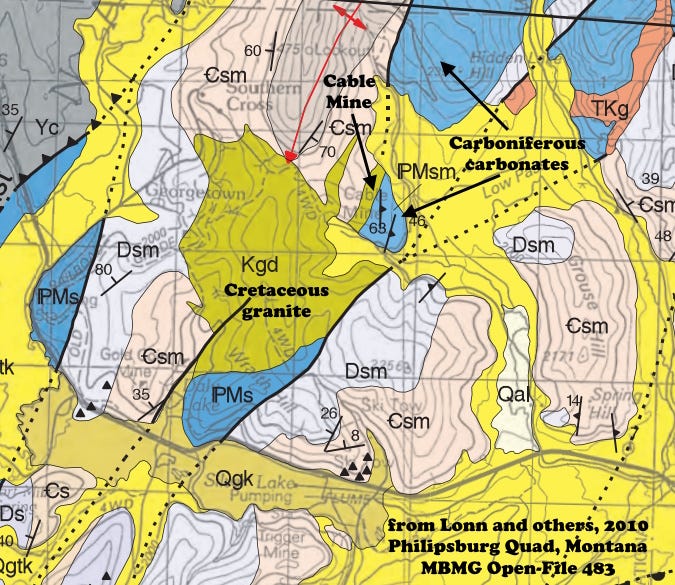

The Cable Mine (also called the Atlantic Cable, part of the Georgetown or Southern Cross Mining District) is about three miles east of Georgetown Lake. It lies in a small block of probable Mississippian (Lower Carboniferous) Madison Limestone that was metamorphosed to marble by a small granitic intrusion that is probably a satellite to the Philipsburg Batholith to the north. These granites were intruded and brought in the mineralizing fluids about 75 million years ago, essentially the same time as the Boulder Batholith, whose mineral-rich fluids were concentrated at the Butte Mineral District, the “Richest Hill on Earth.”

Neither scheelite nor powellite has been reported from the Georgetown District, but scheelite is well known from mines in similar settings around southwestern Montana, even though there are only two photos of scheelite on MinDat from the entire state. I’ve collected tiny bits from both the Calvert and Ivanhoe Mines (which was the leading producer of tungsten in Montana in the mid-1950s). So I think its presence as a minor mineral at the Cable Mine is reasonable.

Scheelite was named for Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742-1786), a Swedish chemist. During a professional career that lasted barely 15 years, he discovered oxygen (Joseph Priestly published first so gets the credit), chlorine, molybdenum, and barium (Scheele recognized the new element, but Davy was the first to isolate it), and made tungstic acid from the mineral then called “tungsten” (later, scheelite). The element tungsten was isolated from the acid by Spanish brothers, chemists José and Fausto Elhuyar. Scheele also first synthesized citric acid and many other compounds, and developed a way of mass-producing phosphorus that made Sweden one of the world’s leading producers of matches.

“Tungsten” means “heavy stone” in Swedish, but the symbol for the element, W, reflects the common European name for the element, wolfram. That name is from the mineral wolframite (iron-manganese tungstate), from German "wolf rahm" ("wolf soot" or "wolf cream"), the name given to the mineral by Johan Gottschalk Wallerius in 1747. This in turn derives from Latin "lupi spuma", the name Georg Agricola used for the mineral in 1546, which translates into English as "wolf's froth" and was a pejorative reference to the large amounts of tin lost during tin smelting when wolfram was present (according to Wikipedia). Alternatively, wolfram may be a combination of words meaning “wolf” and “raven,” two of the animals identified with the Norse god Odin and used as a name.

William Harlow Melville named powellite in 1891 in honor of the American geologist and explorer, John Wesley Powell (1834-1902), second Director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Thanks to Bruce Cox for giving me this pretty rock. Its starry fluorescence makes it pair well with the label of this Tasman Skies IPA from Equilibrium Brewery in Middletown, New York (it also makes me glad I don’t collect beer cans, because if I did, I’d have wanted to keep this one after I finished it last week):

Scheele discovered oxygen, Joseph Priestly published first, and Antoine Lavoisier named it 😁