I have one thing in common with Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman besides our first names: as boys we both collected stamps, and we were both enamored of the diamond-shaped and triangular stamps from Tannu Tuva. They’re from a really obscure place, between Siberia and Mongolia, and its capital, Kyzyl, “doesn’t even have a proper vowel,” according to Feynman.

Feynman’s obsession with Tannu Tuva became a book by Ralph Leighton (“Tuva Or Bust: Richard Feynman’s Last Journey”). My connection is much less; I wish I could share with you a mineral from my collection that originated there, but the level of obscurity is high. I don’t have any tikhonenkovite, a hydrous strontium-aluminum fluoride described in 1964 from its type (and only) locality in Tuva, nor any karasugite, also from the Karasug rare-earth-strontium-barium-iron-fluorite deposit about 150 km west of Kyzyl.

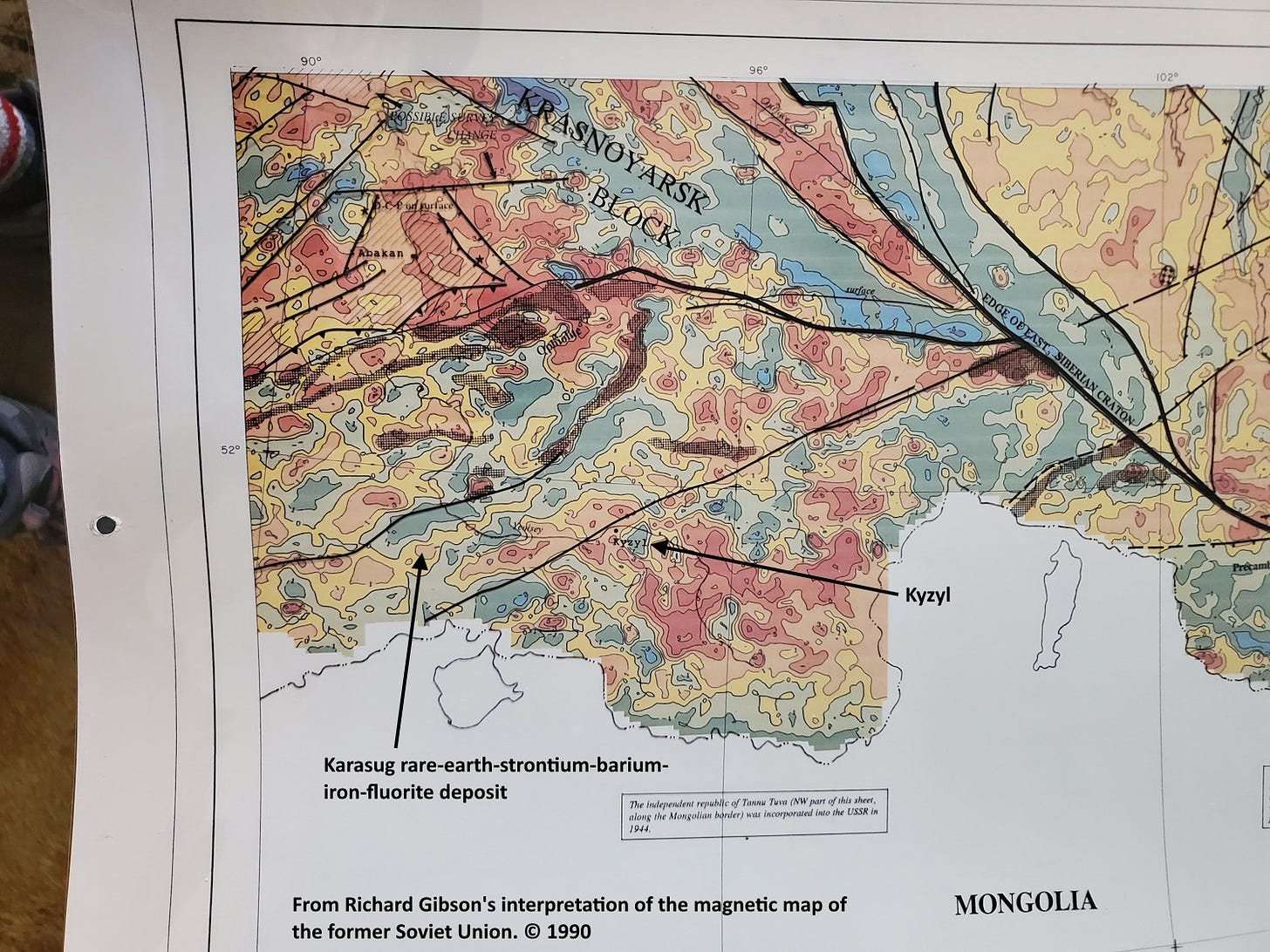

I did work on the area as part of my 1990 interpretation of the Magnetic Map of the Former Soviet Union, although since that project was aimed at hydrocarbon exploration, the Tuva region, which has mostly crystalline metamorphic and volcanic rocks (not usually good hosts for oil and gas) on the surface, got a limited look at the time.

The magnetic map shows a lot of alternating highs and lows, typical for volcanic rocks, but some of the magnetic high zones (meaning there’s a lot of magnetite in the rocks there) correlate with ophiolites, slices of oceanic crust pushed onto the continent during tectonic collisions. Tannu Tuva is just west of the southwestern margin of the Siberian Craton (shown on the map), with a smaller probable continental fragment (the Krasnoyarsk Block) west of that. Much of the area of Tannu Tuva itself is probably another small mostly continental block, complicated by those ophiolites and probably some island arc material as well, and even a few areas of Paleozoic sedimentary rock. There’s really nothing in the magnetic data (at least at this scale, 1:2,500,000) to distinguish the Karasug deposit from many similar areas.

To the south (off the magnetic map) most of Mongolia for many hundreds of kilometers is also a complex region of many terranes, from continental blocks to island arcs to oceanic crust. Those bits were slammed into the Siberian Craton (“craton” means “strong,” a big resistant block of continental crust) when the mid-sized North China Block pushed the bits northward, somewhat like India pushing the Himalaya into Eurasia millions of years later.

The amalgamation of North China, the blocks in Mongolia and Tuva, and the southwestern side of East Siberia took hundreds of millions of years beginning as long ago as 1,000 million years, in the Late Precambrian, but continuing at least to the Permian (250 million years ago) when the last remaining oceanic basin (the Paleo-Tethys) was closed as the supercontinent of Pangaea was formed. The collision of India, beginning about 55 million years ago and continuing to the present, closed the Tethys Ocean and keeps squeezing, deforming, and metamorphosing the entire region as well. There are a lot of metamorphic rocks as well as the collision-related volcanics and ophiolites in Tuva. Consequently I did not recommend much in the way of oil exploration targets there!

The multiple collisions over millions of years, involving highly diverse components, resulted in a mountain belt called the Tuva-Mongolia Orocline (Lehmann and others, 2010, Structural constraints on the evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt in SW Mongolia: American Journal of Science, 310:7, 575–628). “Oroclines” (from words meaning mountain and to bend) are large regional curves in mountain belts. They may relate to the original geometry of the blocks and materials involved, but often they represent the curvature necessary to accommodate the interactions of those pieces. As such, oroclines provided significant support for the developing ideas in the 1950s and 1960s that led to Plate Tectonics. Tuva and Mongolia are part of the vast Central Asian Orogenic Belt (“orogeny” means mountain-building).

The weird minerals I mentioned above occur in carbonatites, essentially formerly molten limestone (or at least calcite, calcium carbonate) accompanied by unusual elements. They are usually associated with rifting, pulling apart, rather than the compression generated by all the collisions I described, but collision is never pure and simple. There can be plenty of pull-apart situations during collision, especially if the collision is oblique or complicated by pre-existing weak zones. The Bayan Obo rare-earth deposit (the largest in the world) is in a carbonatite in northern China, across Mongolia from Tannu Tuva. It formed initially in a Precambrian rift setting, complicated by all the later collisions. Bayan Obo makes China the leading producer (by far) of rare-earth elements in the world. It’s also the world’s largest fluorite deposit. (For more about Bayan Obo, see p. 62-63 in “What Things Are Made Of”.)

While the stamps of Tannu Tuva are exotic and depict interesting nomadic scenes, the stamps themselves are not particularly valuable. There must have been a lot of them, since they were cheap enough for 12-year-old me to buy, and they are mostly still pretty cheap today. But most of them probably never saw Tannu Tuva – they were likely printed in Moscow for sale to collectors. One stamp shows a race between a camel and a locomotive, even though there was no railroad in Tuva when the stamps were made in the 1930s (and there is still no railroad there). For a time, some philatelists considered them labels, not primarily for postal use, but today most stamp catalogues do list them. Examples that are clearly postally used are a lot more valuable than the others.

The Tuvan People’s Republic was nominally independent from 1921 to 1944, like Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, but like them, it was incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1944 and unlike them, it remains part of the Russian Federation today. While it’s perhaps likely that few people know of Tannu Tuva, I can’t say that about many of my friends here in Butte, because we had the pleasure of hosting Tuvan throat singers at one of the recent Montana Folk Festivals.

Sources: Interpreted magnetic map by me (data digitized from published Soviet maps); stamps in my collection; tectonic map from Liu and others, 2016, A review of the Paleozoic tectonics in the eastern part of Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Gondwana Research, 43.

Great article Richard. I am one of those (probably) many people that have never heard of Tanna Tuva!