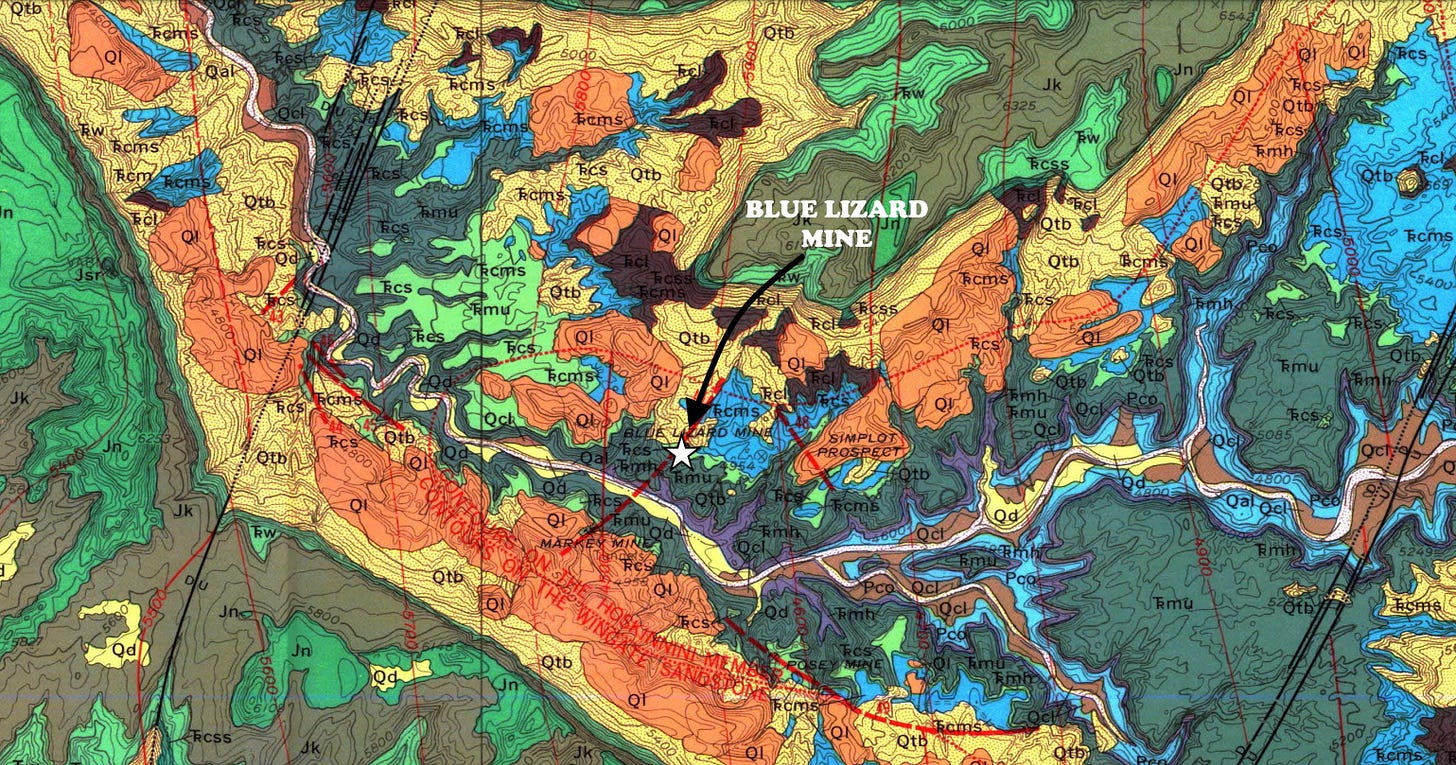

The USGS map that shows the location of the Blue Lizard Mine (associated with the bright apple-green Trcs, Shinarump) has to be one of the more psychedelic maps the USGS has produced. It is from Thaden and others, 1964 (based on work done mostly in the early 1950s), Geology and ore deposits of the White Canyon area, Utah, USGS Bulletin 1125, prepared for the US Atomic Energy Commission when the United States was aggressively exploring for domestic uranium resources. For lack of economic deposits, the US today imports about 95% of the uranium we feed to nuclear power plants.

Although the label sounds confident, in reality the white fibrous stuff is only “probably” belakovskiite and the yellow is just “likely” natrozippeite. If you never heard of those minerals, welcome to the club. I never heard of any of the 23 type locality minerals from this locality, nor 31 of the other minerals known from the Blue Lizard Mine, San Juan County, Utah. Many of the type locality minerals have only been described in the past ten years, some of them as recently as 2021 (and more are likely to be found).

The deposit was recognized in 1898 by John Wetherill, a member of the ranching family that explored the Four Corners region and rediscovered Anasazi ruins in what is now Mesa Verde National Park. The mine claim was established in 1943 in a mineralized zone of the Shinarump Member of the Triassic Chinle Formation, to exploit uranium and copper ores.

The uranium-bearing deposit is in a channel in the Shinarump that contained a lot of wood, which in turn became carbonized and was partially replaced by uranium and copper compounds. The Shinarump there (based on the matrix in my specimens) is a coarse, poorly sorted and poorly rounded sandstone, but in places it is a conglomerate or siltstone. Economic uranium ore (mostly uraninite) seems to be strongly controlled by the positions of channels in the Shinarump, where porosity and permeability, together with the presence of carbonized plant remains, provided both conduits and reservoirs for deposition of the uranium minerals.

Although the minerals present include primary sulfides and oxides of copper and uranium, such as bornite, chalcocite, and uraninite, the dozens of weird things are mostly complex sodium-uranyl-sulfates with various amounts of hydroxyl or water in the crystal structure. Some of the minerals differ from each other only in the number or position of (OH) or H2O groups. Many are named for pioneers in the study of uranium and radioactivity, including oppenheimerite, ottohahnite, klaprothite, fermiite, and feynmanite. Most of the newly described minerals are probably post-mining alteration products; the minerals are found often on the walls of mine tunnels.

Natrozippeite, Na5(UO2)8(SO4)4O5(OH)3 · 12H2O, is yellow, but so are 5 or 6 other minerals from Blue Lizard, so it’s impossible to be sure what species this is without careful analysis. I say it’s natrozippeite because that appears to be about the most common of the similar yellow minerals from there, and it is intensely fluorescent as some of the other yellow minerals are not. The belakovskiite is a little more likely because the white fibrous nature is less ambiguous, but still not certain. It’s Na7(UO2)(SO4)4(SO3OH)(H2O)3.

Zippeite honors Austrian mineralogist František Xaver Maximilian Zippe (named for him in 1845), and belakovskiite was named in 2013 for the curator of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Moscow, Russia.

The vitreous green mineral above is probably johannite, Cu(UO2)2(SO4)2(OH)2 · 8H2O, but there are several other green minerals at Blue Lizard that it could be, including fermiite Na4(UO2)(SO4)3 · 3H2O.

Above: Late-stage malachite (copper carbonate) on sandstone. The sand grains are about 1.5-2.0 mm across.

Today, the United States is dependent on imports for more than 95% of the uranium we use in nuclear power plants (source: US Energy Information Administration). Sources in 2022 were Canada (27%), Kazakhstan (25%), Russia (12%), Uzbekistan (11%), and Australia (9%), with 6 other countries (Germany, Malawi, Namibia, Niger, South Africa, plus domestic US production) accounting for an additional 16%. In May 2024 uranium imports from Russia were banned, effective in August 2024. That (and generally high energy prices, increased demand, and low inventories) has made the price of uranium surge from about $25-$30 per pound since 2016 to near $90 per pound in mid-2024.

Expanded somewhat from an old Facebook post. I do this to get these posts into a location that is more findable (for me, too). Apologies to my Facebook friends for whom this is repetitious.

I have several friends that were responsible for finding many of the recent new minerals from here. They are serious amateur collects with the good fortune to have working associations with a number of mineralogists, thus enabling them to get the necessary analytical work done to describe new species.

Cool pictures and great descriptions. I wasn't aware the US imported so much uranium!