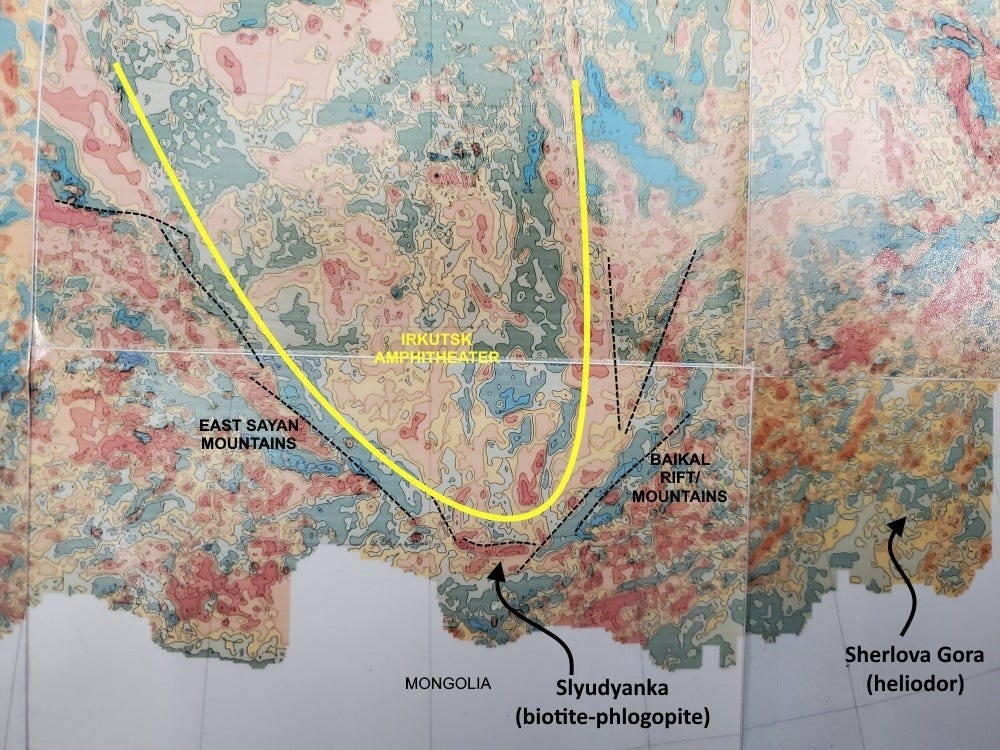

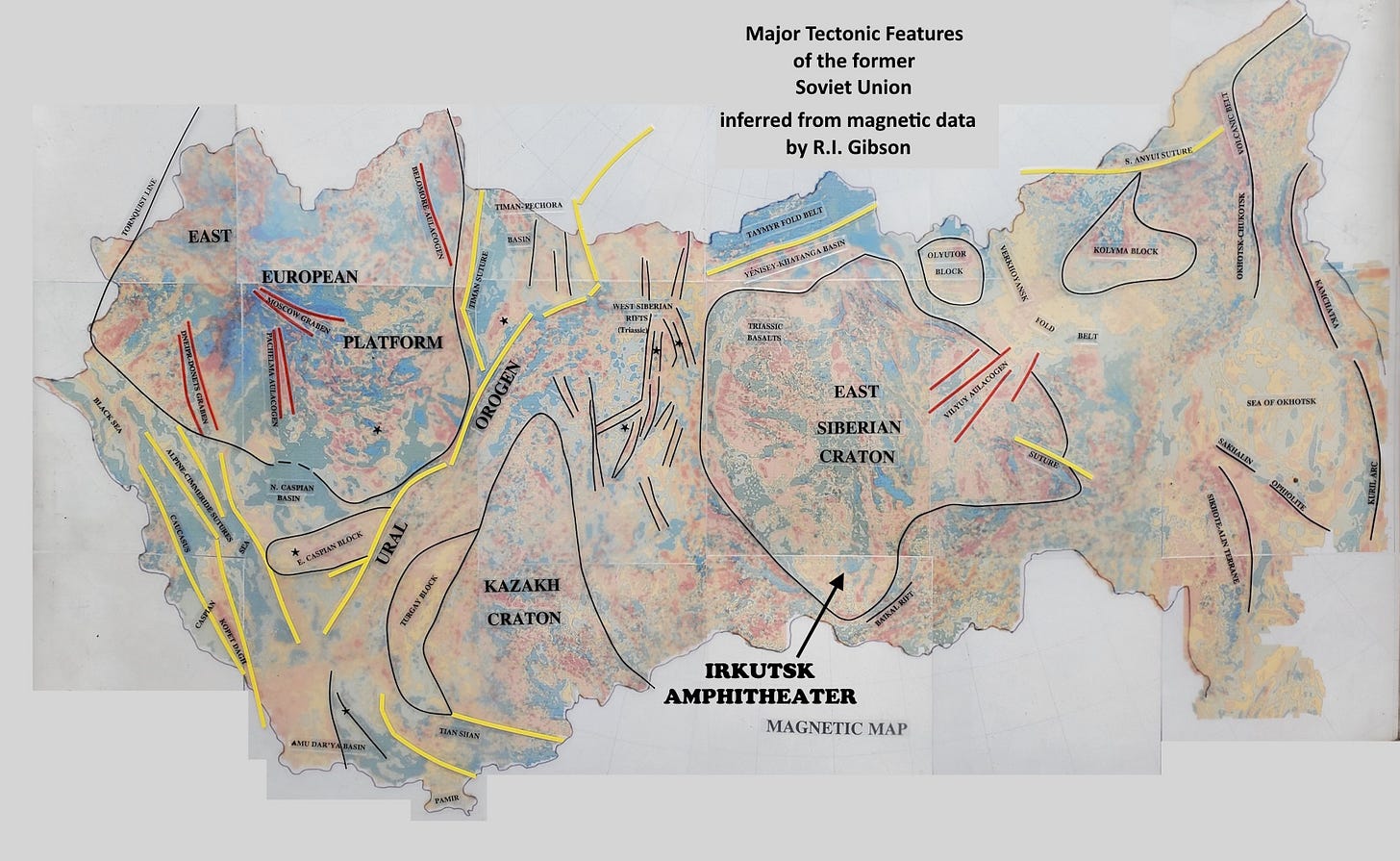

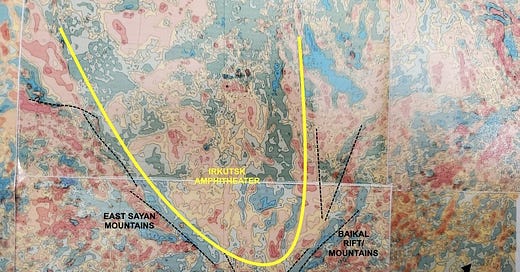

The Irkutsk Amphitheater isn’t some big music venue in Siberia. It is a vaguely amphitheater-shaped depression west of Lake Baikal in Siberia, more than 600 km wide (comparable to the distance from Butte, Montana to Salt Lake City, or Melbourne to Canberra, Australia). It’s bounded by high mountains that are ultimately the result of the collision between India and Eurasia 2,500 kilometers to the south. The peaks of the East Sayan Mountains west of the city of Irkutsk reach heights of nearly 3,500 meters (11,000+ feet) and the Baikal Mountains to the east are around 2,500 meters. The elevation in the Angara River basin in the heart of the amphitheater is only 500-700 meters above sea level.

This area is sort of the southern “prong” of the East Siberian craton, poking down into and acting as a buttress to the weaker rocks that the India collision is pushing northward and around it. The rocks on the surface are early Paleozoic rocks, mostly Cambrian and Ordovician in age (540 to 450 million years old) that rather thinly cover older Precambrian rocks. Those Precambrian rocks are actually pretty young for Precambrian – around 1,200 to 570 million years old.

1,200 to 570 million years ago is a strange time period in earth history. There are not that many places where rocks of that age are preserved at all, and in fact when I was a freshly sprouted geologist, I learned that a large part of that time was called the “Lipalian Interval” – a time when few rocks were preserved, and those that were contained next to no fossils, and the few fossils that WERE present were primitive forms, nothing like the abundance and complexity that seemed to explode into the geologic record at the start of the Cambrian period – the Cambrian Explosion.

Since 1966 when I learned about it, rocks and fossils have been found and dated to provide a degree of continuity over that interval, but it still remains enigmatic. Part of it is a time (around 650 million years ago) when “snowball earth” may have completely, or almost completely, enveloped the planet in ice and snow for millions of years, and while there WAS life, it certainly did not exist in the volume and diversity it would by Cambrian time. But maybe there were exceptions…

There’s actually oil in those Precambrian rocks in the Irkutsk Amphitheater. Oil doesn’t come from dinosaurs, it comes from plants, and algae are probably the biggest source for the hydrocarbons that become oil and natural gas. But enough to make commercial deposits of oil and natural gas? In big basins, it’s not that hard to squeeze oil from younger rocks that are buried deeper into older rocks that are regionally higher, and a lot of the oil and gas in the Irkutsk area is on flanks of highs, significantly higher in the subsurface than considerably younger rocks that might have been oil source rocks. But they weren’t source rocks. The younger Cambrian and Ordovician rocks, on the surface and in the subsurface, have been studied enough that we know they really are not oil source rocks.

The best oil source rocks in the Irkutsk Amphitheater are of Riphean age – a stage of the Proterozoic part of the Precambrian that ranges in age from about 650 to about 1,600 million years. The Riphean Shuntar formation is between 1,050 and 1,350 million years old, and it consists of organic-rich black shales and limestones and dolomites that also contain a lot of organic material. As much as a third of the 1,000-meter thickness has total organic carbon (TOC) of around 4%, with a high at 8.7% TOC. That is an absolutely phenomenally huge value for TOC; for comparison, the excellent oil source rocks in Saudi Arabia average 3% to 5% TOC. The rocks were deposited in a restricted, anoxic back-arc setting during one of the rift-collision-rift orogenic cycles that impacted this area more than 500 million years ago. It must have been large, long-lived, and supportive of a LOT of algae, bacteria, and other microorganisms that died off but were not oxidized, washed away, or otherwise removed – they became part of the rock.

While there is some oil, most of the hydrocarbons that accumulated in and on the flanks of the Irkutsk Amphitheater have been so cooked and modified over time that they are now natural gas. Perhaps the most amazing thing about it all is that ANY such material has survived for so long!

I don’t have any minerals from the Irkutsk Amphitheater itself, but here are two from nearby. Their localities are given on the map at the top.

Heliodor is a yellow variety of beryl, Be3Al2(Si6O18). This one is from a well-known locality at Sherlova Gora, Adun-Cholon Range, Nerchinsky District, Zabaykalsky Krai, also known as Mt. Schorl, Russia. It seems to me to be too greenish to really be called heliodor, but that’s how it was labeled.

A nice sharp little crystal of the mica phlogopite, KMg3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2. Phlogopite is monoclinic crystallographically, but its molecular unit cell is pseudohexagonal, sometimes producing six-sided crystals like this one, but it is not in the hexagonal crystal system. From the mica quarry at Slyudyanka, Lake Baikal area, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia; originally labeled biotite, which is now a group, and from this locality phlogopite is more likely. 8x7 mm.

The thought of the collision of India with Asia forming mountains 2500 km away really speaks to the force involved in that tectonic motion!

Ah yes. Precambrian hydrocarbons. Back when I worked in western Montana (minerals exploration) I remember there being some interest in possible Belt rocks having some, although little, possibility for hydrocarbon potential. I never kept up with the interest and it seems that it was one of those geo- optimistic ideas. Based on this post I wonder if the Belt rocks were just too old. There is no lack of section, but too early for hydrocarbons to be preserved or even deposited. I am sure that the Irkutsk Amphitheater oil/gas occurrences probably figured into the discussion. I haven't thought about Belt rocks in some time so thanks for the post. Happy Lipalian Interlude!