A copy of a 1909 treatise on the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, by Captain F. R. Sedgwick (R.F.A., Royal Field Artillery), serves as a springboard for this post about the use and role of geology in military operations.

The Russians in that war are credited with the first widespread wartime use of geologists to assist in siting and construction of fortifications. The Japanese also used the war to begin the first comprehensive geologic mapping of Chosen (Korea), and those maps were still useful 50 years later for the American effort in the Korean War, and to an extent they remain some of the most thorough geologic maps of North Korea generally available outside that territory.

I’m prejudiced and I believe that geology truly is everywhere, and has a role in everything, but it should be evident that things like the nature of terrain (predictable or otherwise), the underlying rocks, water systems, and more are all important to military movements and strategic and even tactical planning.

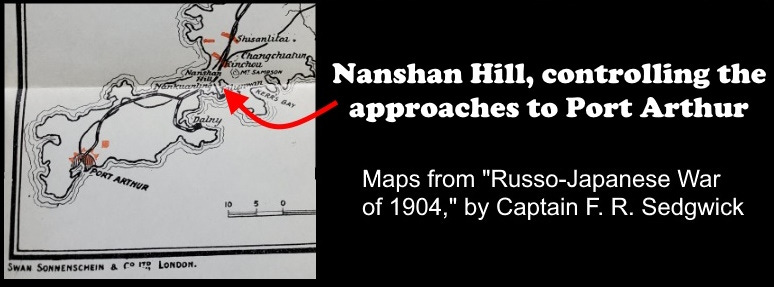

The causes of the war were complex, but among other things Imperial Russia sought a warm-water port, specifically Port Arthur, the port at the tip of the Liaodong Peninsula. China had leased the port to Russia but retained control of the peninsula, so Russia’s access was limited; Japan’s imperial ambitions included an expanded sphere of influence in Korea and adjacent areas of China and opposed Russia’s expansionism. Unexpectedly, Japan won the war, and the consequences for the rest of the 20th Century were not trivial.

The Liaodong Peninsula exists because of complex tectonics. The oldest rocks there are Paleoproterozoic, about 2100 to 1800 million years old, and may record part of the collisions that created the early supercontinent of Columbia (Yang and others, 2019, Tectonics of the Paleoproterozoic Jiao-Liao-Ji orogenic belt in the Liaodong peninsula, North China Craton: A review: Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, Volume 176, pages 141-156).

That’s far too long ago to have much direct impact on modern geography, but it can still exert subtle influences. The convoluted coastlines of northeastern China, including the Bohai Sea (called the Gulf of Pecholi on these old maps) and Yellow Sea and the Liaodong and Shandong Peninsulas, are more controlled by modern tectonics, specifically the active Tanlu fault that runs through the Bohai Sea and north of Liaodong. It is part of a huge active fault system that helps define the eastern side of the North China Craton, one of the major building blocks of southeast Asia. Movement on the Tanlu Fault caused the 1668 Tancheng earthquake (Magnitude 8.5) which killed an estimated 50,000 people. The Tangshan earthquake in 1976, which killed at least 246,000 people, was not on the Tanlu Fault but on related faults that help define the northwestern coast of the Bohai Sea.

More specifically, and more pertinent to the efforts of the Russians and the Japanese in 1904, the isthmus, the narrow neck of land that separates the main Liaodong Peninsula from its terminus at Port Arthur, is underlain by Triassic dikes that intrude Proterozoic sediments, all presumably much less resistant than the Paleoproterozoic gneiss that occupies much of the main Liaodong Peninsula (in a metamorphic core complex). Geology is why that narrow, strategic neck of land exists.

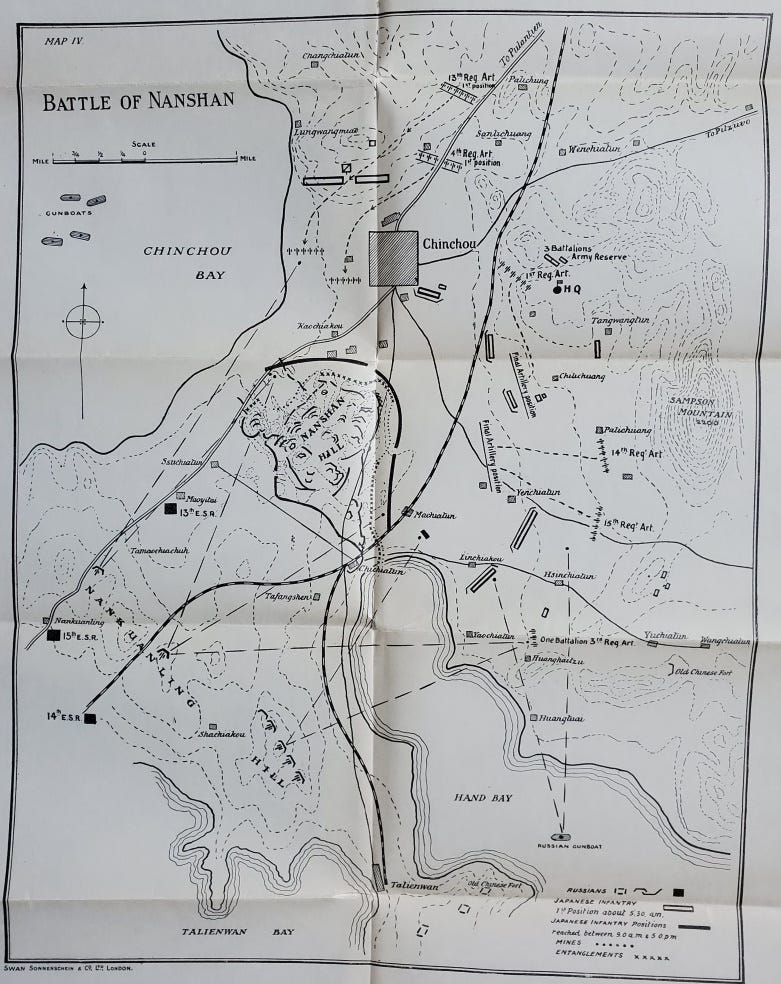

The isthmus is commanded by a small hill, the site of the Battle of Nanshan on May 24-26, 1904 (maps above). The hill was held by the Russians, fortified with mines and barbed wire entanglements, together with Maxim machine gun emplacements, but nonetheless the Japanese took the hill. Nanshan is an erosional remnant of probable sandstone in the Neoproterozoic sedimentary rocks near the tip of the peninsula, which are otherwise mostly less-resistant carbonates and mudstones.

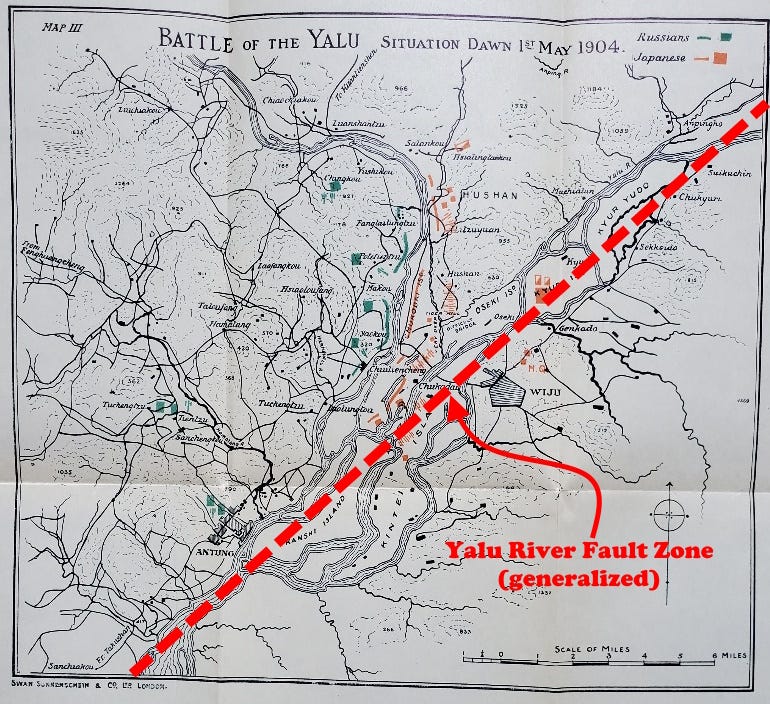

The Yalu River, which today forms the border between North Korea and China, was the scene of the first major land battle of the war. The Yalu River is localized by the 700-km-long Yalu River Fault Zone, a complex element of the eastern margin of Asia that was active in diverse ways during most of the Cretaceous, spanning a time from about 140 million to 70 million years ago (Zhang and others, 2018, Strike-slip motion within the Yalu River Fault Zone, NE Asia: The development of a shear continental margin: Tectonics, 37:6, p. 1771). The zone is not especially active today, but earthquakes do occur. It also helps to localize the southern side of the Liaodong Peninsula, while the Tanlu Fault controls the northern side.

As an aside, Swan Sonnenschein & Co., London, which printed this book and its 12 separate maps in 1909, also published the English translation of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

I had this 1909 book a year longer than it had already existed when I got it in a thrift store in Flint, Michigan, in 1964 for ten cents. It recently went to a new appreciative owner.

I only have one specimen from Liaoning Province, home to the Liaodong Peninsula, and it’s a fossil. These large mayfly larvae are remarkably well preserved for being 123 million years old, but they come from the Yixian formation, a lagerstätte, a place of exceptional fossil preservation. The word is German for “storage place,” based on the same root as lager beer, which was traditionally stored in cold caves during the fermentation process.

The Yixian formation preserves an amazing variety of fossils, ranging from dozens of species of soft-bodied insects to feathered dinosaurs, pterosaurs, many early species of birds, turtles, more than 15 species of mammals, fish, flowers, and much more. Collectively the fossils represent part of the Jehol Biota, one of the most extensive and well preserved Cretaceous (or any age) fossil assemblages in the world.

The lush ecosystem in which all these animals and plants lived was a lakeside forest (or probably several lakes) that was episodically buried in fine-grained volcanic ash, resulting in the exceptional preservation. The lake sediments were also fine grained, to further contribute to the preservation.

The lakes were located on the northern side of what is now the Bohai Sea, and the basins they occupied were probably related to complex extension, possibly large-scale detachment faulting (sliding of huge, mountain-range-size blocks, off regional uplifts) that in turn was a response to the complex interactions between what is now northeastern China and the Cretaceous Pacific oceanic plate (Jia and others, 2021, Tectonic Controls on the Sedimentation and Thermal History of Supra-detachment Basins: A Case Study of the Early Cretaceous Fuxin Basin, NE China: Tectonics 40:5).

The name Liaoning is from the Liao River, whose name’s origin is obscure, plus “ning,” peace. Liaodong means East Liao. “Bohai Sea” is actually a redundancy, since “hai” means sea in Chinese.

This post was modified from an original post I did on Facebook.

Geology is destiny... Love the satirical map!