The Sea of Okhotsk, between the Kamchatka Peninsula and Sakhalin Island in far eastern Asia, is larger in area than Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Wyoming, Utah, and West Virginia combined, and slightly smaller than Queensland State, Australia.

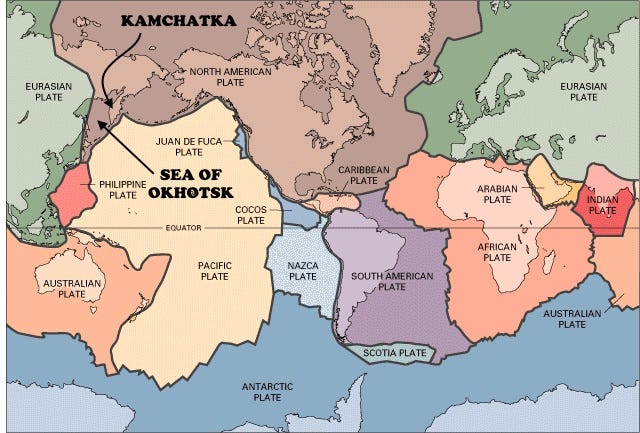

Except where it is bounded by the Kurile Island magmatic arc where the oceanic Pacific Plate is subducting, most of the Sea of Okhotsk is underlain by a complex amalgam of rocks that were added to the North American Plate. The Sea of Okhotsk is generally pretty shallow (averaging about 860 m or 2800 ft). And yes, tectonically, it is mostly part of the North American Plate together with far eastern Siberia onshore as well. A recent study (Hindle and others, 2019, The Ulakhan fault surface rupture and the seismicity of the Okhotsk–North America plate boundary: European Geosciences Union, Solid Earth, 10, 561–580) suggests that the Okhotsk region is actually a distinct microplate, fairly recently separated (and continuing to separate, albeit slowly in geological terms) from North America along a fault zone.

The Eurasia-North America plate boundary is poorly defined in Siberia because the two plates are more or less locked with each other and are moving together there, even while they move apart in the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans. The boundary is clearer in Sakhalin Island where faults are mapped and moderate seismicity indicates that there, Eurasia is pushing (slightly) to the east, up and over the North American Plate in the Sea of Okhotsk. The most prominent boundary of the Okhotsk microplate is along the Kurile Island trench and magmatic arc, with its back-arc basin in the Sea of Okhotsk where water depths reach nearly 3400 meters (11,000 ft), much deeper than most of the Sea of Okhotsk.

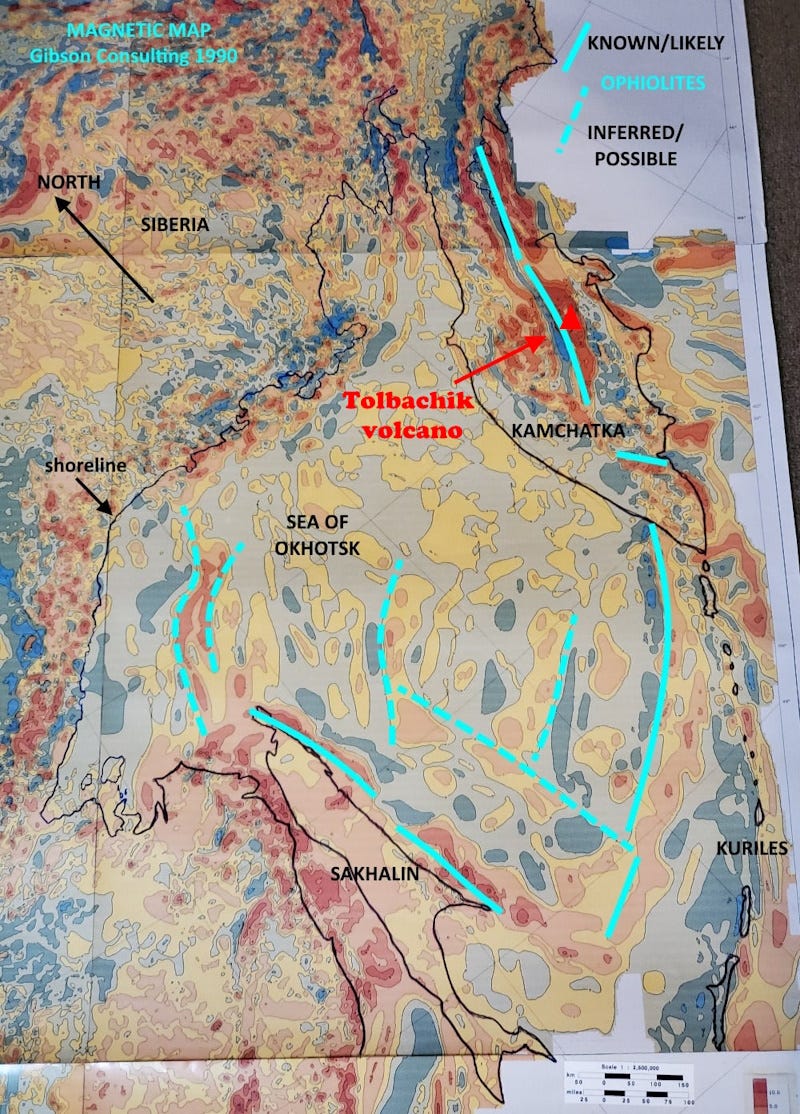

Magnetic data that I studied in 1990 as part of a comprehensive tectonic interpretation of the entire former Soviet Union are a little problematic in this area, because the data in the Sea of Okhotsk are ship-borne data, more wide-spaced and irregular compared to aeromagnetic data. Nonetheless, the magnetic map above shows several prominent curvilinear anomalies in red (magnetic highs, indicating strongly magnetic rocks) that probably represent ophiolites, slices of sea floor that were added to this margin of the continent. Similar features onshore in both Sakhalin Island and the Kamchatka Peninsula are certainly or very likely ophiolites, associated with a lot of other material including island-arc volcanics, sediments in regional basins, and probably some microcontinent blocks. You’d expect such diversity in an area comparable to the region from Seattle to Miles City, to Denver to Flagstaff and back to Seattle in the USA.

An alternative to my explanation of the linear magnetic anomalies in the Sea of Okhotsk as ophiolites is that they represent variations in oceanic (or possibly continental) volcanic plateau rocks, igneous materials erupted into a large pile on the sea floor and subsequently accreted to the continent. Either way, the subsurface rocks in the Sea were added as parts of ongoing collisions that may have begun as long ago as Jurassic time (around 175 million years ago) but that were probably most active from Late Cretaceous time (80-70 million years) into the Miocene (15 to 5 million years ago).

The Kamchatka Peninsula, which defines the eastern side of the Sea of Okhotsk, is largely a magmatic arc related to the subduction of the northwestern Pacific Plate beneath a prong of the North American Plate. In addition to a likely slice of oceanic crust (an ophiolite), the volcanic rocks there appear to be rich in iron because of the intense linear magnetic anomaly present. The Tolbachik volcano in central Kamchatka is type locality for 152 minerals, many associated with fumaroles and other present-day surface and near-surface volcanic activity.

Sakhalin Island, which defines part of the western side of the Sea of Okhotsk, is along a lengthy fault zone that has had a long geologic history. Today the Sakhalin–Hokkaido Fault Zone is a long linear north-south right-lateral strike-slip fault system much like the San Andreas of California or the Alpine Fault of New Zealand (Arefiev and others, 2000, The Neftegorsk (Sakhalin Island) 1995 earthquake: a rare interplate event: Geophysical Journal International, Volume 143, Issue 3). Like most such faults, it’s not a simple straight line, and its oblique movement over time has produced some deep basins along it, occupied by thick piles of sedimentary rocks with some significant oil and gas accumulations.

The longest oil wells in the world are offshore Sakhalin Island. I say “longest” rather than deepest, because these wells turn from near vertical to near horizontal to exploit the oil-bearing formations. The O-14 Chayvo well was drilled about 14,900 meters (49,000 feet), but because of that turn, its end is only at a true vertical depth of about 1,000 m (3,300 feet). The reservoirs are quite young, the Lower Nutov Group of Late Miocene age, about 5 to 11 million years old (Galushkin, 2016, Tectonic History and Thermal Evolution of Sedimentary Basin in the North-Eastern Shelf of Sakhalin Island, Russia: in book, Non-standard Problems in Basin Modelling, Springer International 2016; and Ko, Jaehong, 2010, Petroleum geology of the Sea of Okhotsk region, the Russian Far East: Journal of the Korean Society for Geosystem Engineering 47, 956-974).

The deepest wells in terms of their vertical penetration into the earth are in Qatar, where one well reached 12,289 meters (40,318 feet).

The Kurile Island arc (also spelled Kuril) that defines the active convergent (subducting) southeastern margin of the Sea of Okhotsk was recently identified as the likely site of a significant eruption in 1831, strong enough to affect global climate for at least two years (Hutchison and others, 2024, The 1831 CE mystery eruption identified as Zavaritskii caldera, Simushir Island (Kurils): Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 122 (1) e2416699122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2416699122 ).

The name Okhotsk is from the Okhota River, which in turn derives from the word okat in the language of the Even indigenous people, which means “river,” so “Okhota River” is redundant. The Even people are closely related to but distinct from the somewhat more well-known Evenki people; both are Tungusic people, native to eastern Siberia (about half the 70,000 Evenki live in Manchuria). There are only about 5,700 native Even language speakers in Russia today, although around 22,000 ethnic Evens are scattered across eastern Siberia.

For an interesting look at the European history of the Sea of Okhotsk (and much more), I recommend East of the Sun: The epic conquest and tragic history of Siberia, by Benson Bobrick (Henry Holt & Co., 1993).