Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts have been scheduled for over a month, and they will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them.

The 39-ton bronze Tsar Cannon in the Kremlin in Moscow was cast in 1586. Bronze is an alloy of about 88% copper and 12% tin, sometimes with bits of other metals to increase strength or machinability. Brass, on the other hand, is mostly copper and zinc.

Copper mining in the Ural Mountains dates to the 2nd millennium B.C.E., and the mines there were the likely source of the copper for the Tsar Cannon. In particular the Gumishev (Gumyoshevsky) mine near Yekaterinburg (Sverdlovsk), one of the oldest and richest, averaged as much as 5% copper for many years. It produced copper from the Bronze Age into the 20th Century, and probably contributed ore to create the Tsar Cannon.

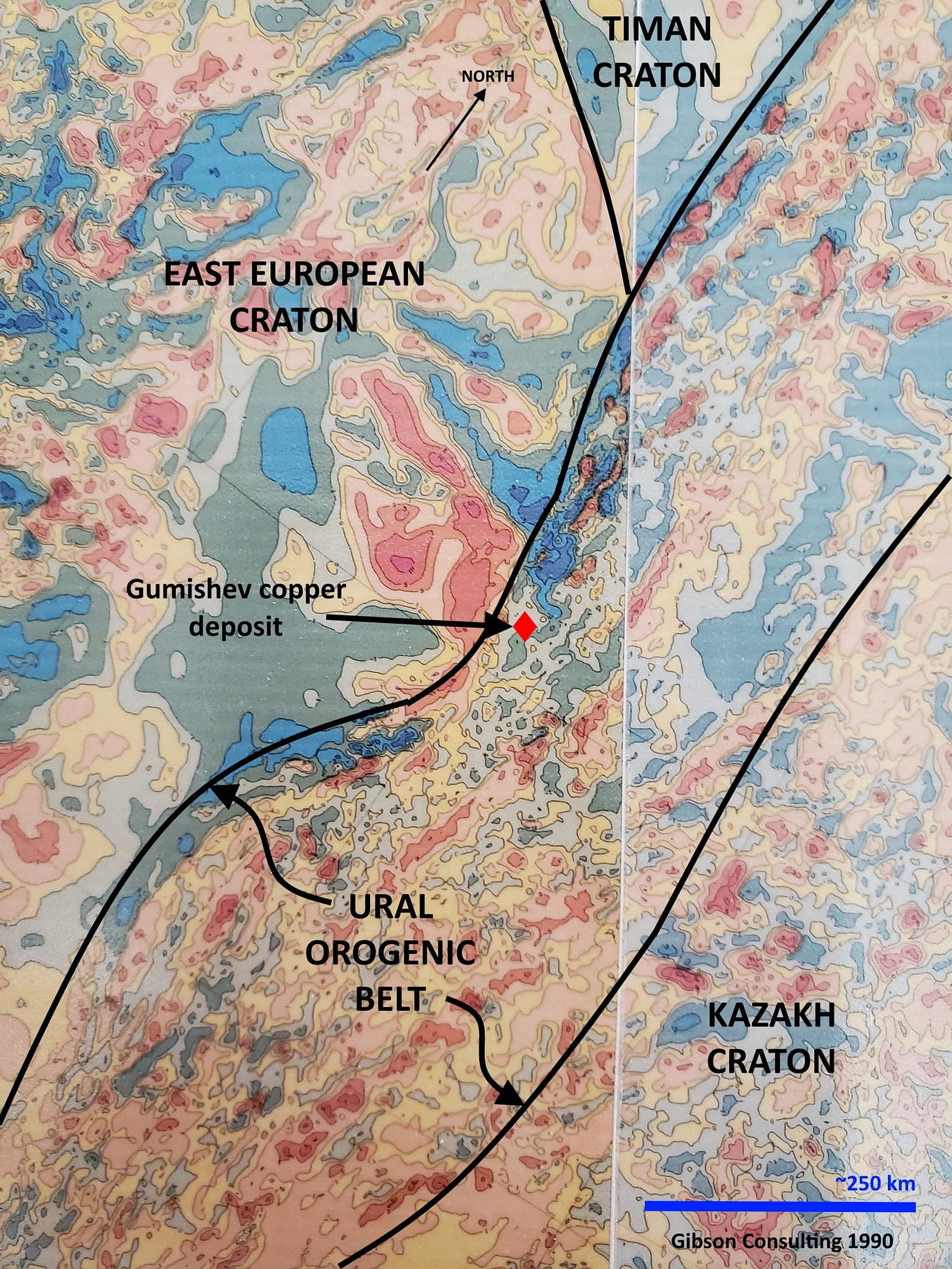

Simplistically, the Ural Mountains were formed in the collision between the Kazakh and East European (Baltic) cratons during Carboniferous to Triassic time, about 320 to 240 million years ago, part of the assembly of the supercontinent of Pangea. But anything that lasted 80 million years is much more complex than that.

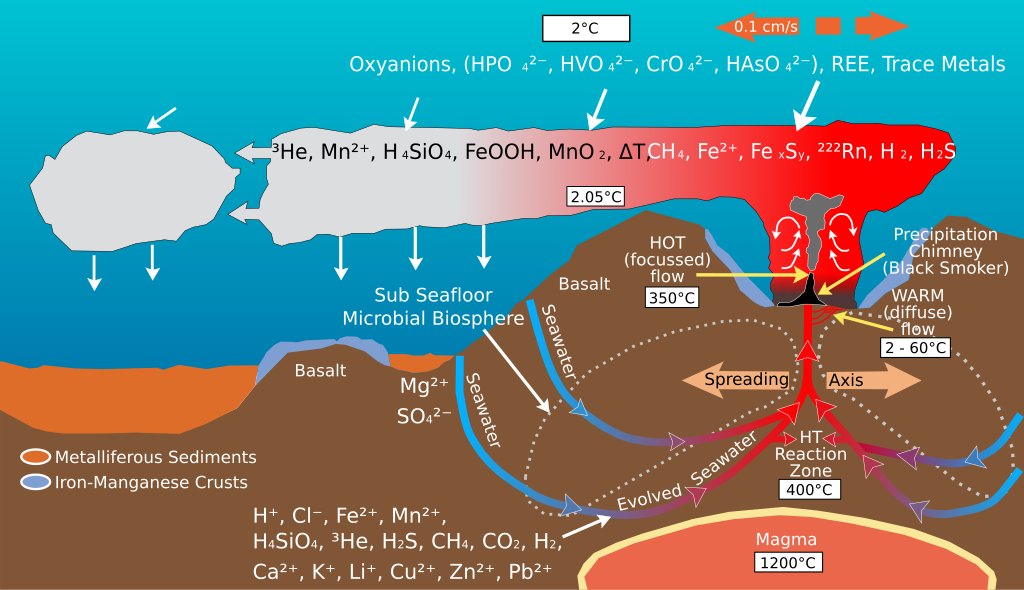

The mineralization in the Urals is related to highly diverse situations. World-class deposits of chromite and platinum are associated with ophiolites (slices of oceanic crust, although some of the Urals complexes are thought to include slices of upper mantle as well; Pašava and others, 2011, Geochemistry and mineralogy of platinum-group elements (PGE) in chromites from Centralnoye I, Polar Urals, Russia: Geoscience Frontiers, Volume 2, Issue 1, pages 81-85) that became involved in the collision. A lot of the sulfides, including ores of copper, formed in the depths of volcanic island arcs or rifts, possibly by incorporation of ‘black smokers,’ mantle-sourced volcanic vents, into the island arcs, which in turn were part of the subduction complexes along the colliding continental fronts (Pushkarev and others, 2013, Geology and ore deposits of the Urals: Mineralogy & Petrology, 107:1). There are also fairly standard copper porphyry deposits (similar to those at Butte, Montana, and at Chuquicamata, Chile) that are related more directly to subduction beneath the continental margin (Plotinskaya and others, 2017, Porphyry deposits of the Urals: Ore Geology Reviews 85:153).

The magnetic map suggests the complexity of the Ural Mountains. Many of the linear red magnetic highs are probably ophiolites or bands of ultramafic intrusions. There’s no obvious correlation between the magnetic map character and the Gumishev deposit, but I’ve never tried to figure that out (my work on the magnetic map of the former Soviet Union was for oil exploration), and to do so would probably require data at a scale larger than this map, which is at 1:2,500,000.

The Tsar Cannon photo is from my trip to Moscow in 1992 to participate in the conference of the Society of Exploration Geophysicists. Although the gun was made during the reign of Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich, the name is probably mostly a reference to its size. It was a symbolic item from its beginning; it may have been fired once, or never (the “cannon balls” in front of it are decorative and are too large to even fit in the gun). The yellow building in the background is the Kremlin Senate Palace, built in 1776-1787 to house the Imperial Russian judiciary and legislative organizations. Lenin lived in the building and parts of it were open for tours until 1994. Today it holds the offices of Russian leader Putin, and it is inaccessible to the public.

A bit of an expensive late 1800's "flex".