First, a big thank you to all you subscribers, commenters, and readers of The Geologic Column. I really appreciate your interest. I try to make these posts hit the “sweet spot” that professional geologists and mineral collectors will find interesting, while non-specialists will also be intrigued to whatever extent possible, all while allowing myself selfishly to learn things. Thanks!

A few years ago, I acquired a 1000-piece collection of microminerals, tiny, often obscure, but always interesting. I recently got interested in the Lovozero Massif, a highly alkaline (sodium, potassium) igneous body in the Kola Peninsula of northwestern Russia near the Arctic Ocean and Finland. Turns out I have 13 specimens from there, all but one of which I’d never heard of, and there are at least four additional minerals (all previously unknown to me) in the specimens but not on the labels. Today’s story is about one of those specimens, only 17 mm by 8 mm in size.

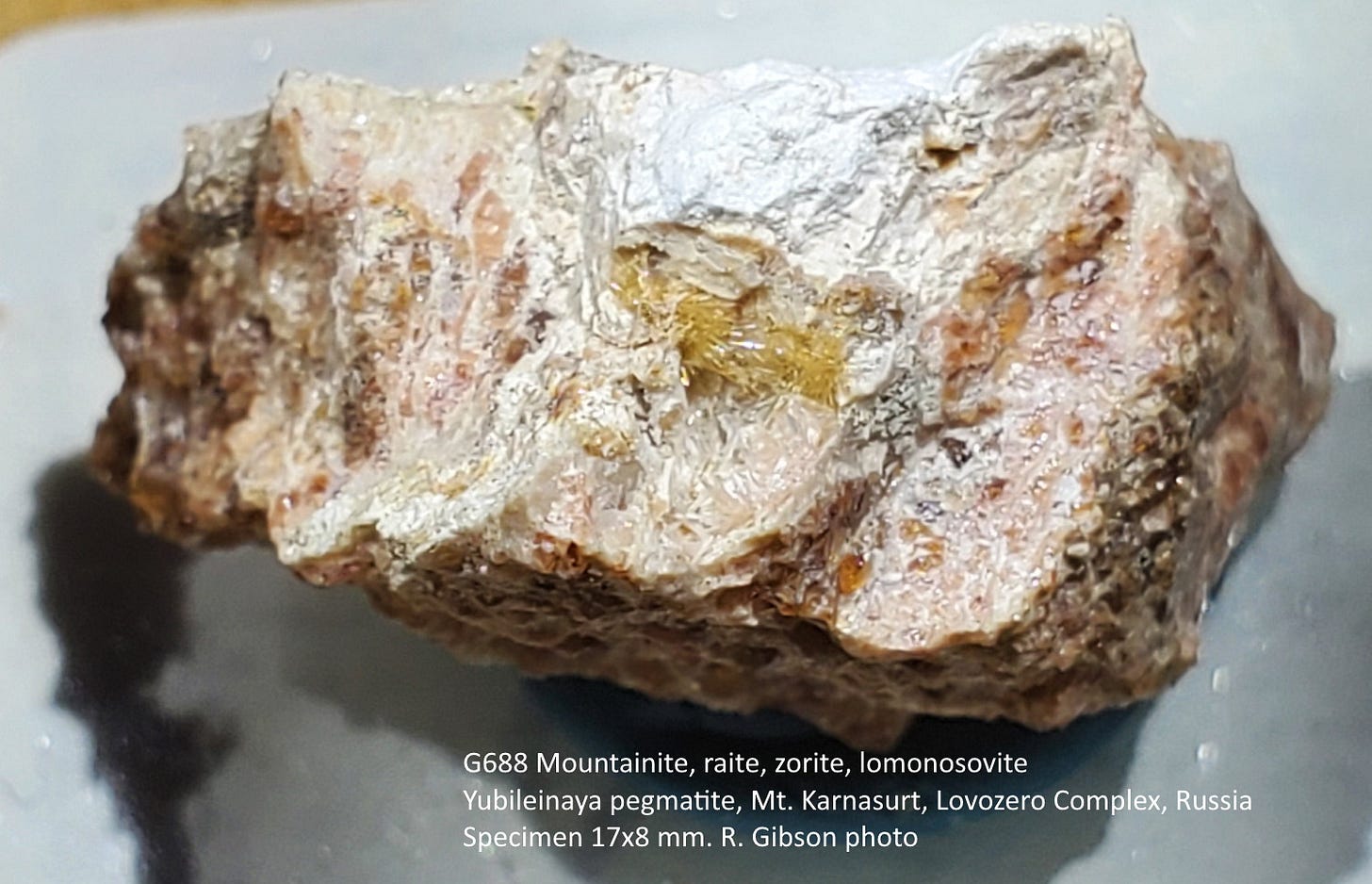

The label said it’s mountainite from the Yubileinaya pegmatite at Mt. Karnasurt, in the Lovozero complex. Mountainite is a strange potassium-sodium-calcium silicate named not for a geographic feature but for Edgar Donald Mountain (1901-1985), a South African geology professor who discovered it. Based on the 10 photos on MinDat, it’s usually a white massive to finely bladed crystalline mineral; mine is the white massive stuff, not very interesting.

But there is a cavity in my specimen with brown needles and pale pink sheaf-like crystals. They are raite and zorite, respectively. Raite is a complex hydrous sodium-manganese-titanium silicate and zorite is hydrous sodium-titanium-niobium silicate, and the Yubileinaya pegmatite is the type locality for both.

The Yubileinaya pegmatite is a vein-like body in the Lovozero igneous complex, just 26 meters long and one meter thick, but 64 minerals have been found in it, including 12 for which it is the type locality (the place where the mineral was first discovered and described). Zorite has never been found anywhere else, and raite comes only from 5 other localities, two in Quebec and the others also in the Kola Peninsula of Russia. The whole Lovozero complex is home to 110 type locality minerals and 407 different minerals in total.

My tiny little piece of rock also has a matrix of lomonosovite, a brown sodium-titanium silicate-phosphate (type locality elsewhere in the Lovozero complex) and a layer of bright green aegirine laths. Aegirine, sodium-iron silicate, is a fairly common pyroxene and is the only thing in the 13 specimens I have from Lovozero that I’d ever heard of before.

Aegirine and the weird minerals are indicators of peralkaline rocks, which have little aluminum and a lot of sodium and potassium, chemistry that prevents feldspar from forming. The rocks at Lovozero are also called “ultra-alkaline” and agpaitic, the latter characterized by minerals containing rare earths, titanium, zirconium, and fluorine.

The Lovozero igneous complex intruded Archean rocks (more than 2,500 million years old) during Devonian time, about 362-372 million years ago (Kogarko and others, 1996, Alkaline Rocks and Carbonatites of the World, Part 2: Former USSR: Chapman and Hall, London and New York). Given the strange mineralogy and chemistry, it’s no surprise that rocks like these are rare and require special conditions. There appears to be no strong consensus about the origin and setting of agpaitic rocks, although most appear to be from highly differentiated magmas and many appear to be related to continental rifts (Marks and Markl, 2017, A global review on agpaitic rocks: Earth-Science Reviews, Vol. 173, p. 229-258).

The Devonian intrusive bodies at Lovozero and nearby Khibiny also contain significant quantities of rare-earth elements, reportedly among the largest in the world (Kalashnikov and others, 2016, Rare earth deposits of the Murmansk region, Russia—A review: Economic Geology v. 111, p. 1529-1559). The Lovozero body is a layered intrusion of general laccolith shape, an arched, dome-like roof and a flat floor (Mikhailova and others, 2019, Petrogenesis of the Eudialyte Complex of the Lovozero Alkaline Massif (Kola Peninsula, Russia): Minerals 2019, 9(10), 581). The intrusive complexes, including associated dikes, appear to be related to a failed extensional rift system near the edge of the Baltica (European) Craton (Veselovskiy and others, 2016, Paleomagnetism of Devonian dykes in the northern Kola Peninsula and its bearing on the apparent polar wander path of Baltica in the Precambrian: Tectonophysics, 675:95-102).

Raite was named in 1973 for the 1969-70 Ra expeditions of Thor Heyerdahl, and zorite is from Russian "zoria", meaning "the rosy radiance of the sky at dawn," although most of the 28 photos on MinDat are VERY pale pink, as is my example.

The namesake of lomonosovite, Mikhail Vassil’evich Lomonosov (1711-1765) was a physicist, chemist, astronomer, geologist, and poet (i.e., a polymath) who discovered the atmosphere of Venus based on his observation of the planet’s transit of the sun in 1761, formulated the principle of conservation of mass during chemical reactions, predicted the existence of Antarctica, and, by virtue of his book “On The Strata of the Earth,” published in 1763, more than 20 years before James Hutton’s “Theory of the Earth,” Lomonosov is considered by many to be the father of modern geology.

“Yubileinaya” is Russian for “jubilee” or “anniversary.” I don’t know what celebration may have given the pegmatite that name.

This post is a reprise and expansion of a Facebook post from a few years ago. Apologies to those for whom it is too repetitious!

"all while allowing myself selfishly to learn things" - Same for me Richard! Keep up the good work.

Nice description Richard.

When I first got into minerals it was all the simple, aesthetic, and common ones. When I found out about Kola and MSH and the others, my first realization was "uh-oh, this gets way too deep."