Minerals can do a lot of things, often deviating far from their typical habits. “Habit” has a well-defined meaning in mineralogy, often describing the geometry: bladed, fibrous, tabular, radial, acicular (needle-like), dendritic, botryoidal (like grapes), prismatic, equant, arborescent (like tree branches), foliated, micaceous, globular, mammillary, reniform (like kidneys), stalactitic, and more. Sometimes it’s a specific form defined from a place where it’s prevalent, like Tessin or Muzo.

But minerals sometimes don’t occur in any of their typical habits. Today we visit one of them.

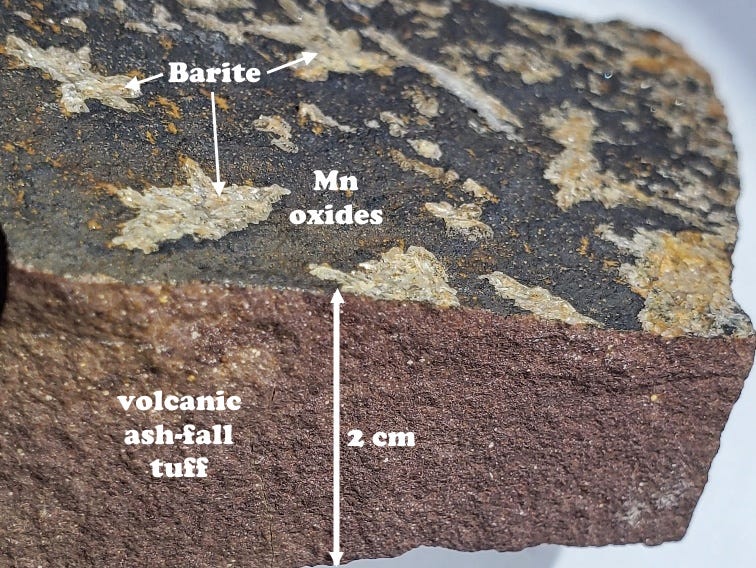

The splotches of white on the rock in the top photo are barite crystals, but they are not flat against the rock as they seem at first. The thin bladed crystals stand at an oblique angle to the substrate, in places almost perpendicular. Although the sprays are as much as two centimeters across, they are barely one millimeter thick. The tops of all the crystals are broken, which reflects their parting from a surface opposite the one you see these crystals on.

The barite crystals grew in a fracture, a crack in the rock, spreading into star-like clusters related to the directions of fastest growth and constrained by the walls of the crack. The crack was probably no more than two or three millimeters wide.

We can tell a lot about the history of this rock, which is from Sherman Butte, west of Rocker, Montana USA. The fine-grained reddish-purple body of the rock is a consolidated volcanic ash fall, red because it is rich in iron. Solidified ash is called tuff, and this is called a welded tuff because it was still warm enough when it fell that the ash particles annealed (welded) themselves to each other to make a hard, solid rock.

The volcanic ash-fall tuff is part of the Lowland Creek Volcanics which erupted between about 53 and 49 million years ago. Big Butte in its namesake town is part of that system.

Because the reddish tuff is coated with black manganese oxides, we know the rock had cracked after it solidified to allow manganese-rich water to deposit the black coating. The Butte mineral district is rich in manganese, among the leaders and possibly #1 in historic manganese production in the United States. Butte is famous for pink crystals of rhodochrosite, manganese carbonate, but black coatings of manganese oxides are abundant, especially on the west side of the district.

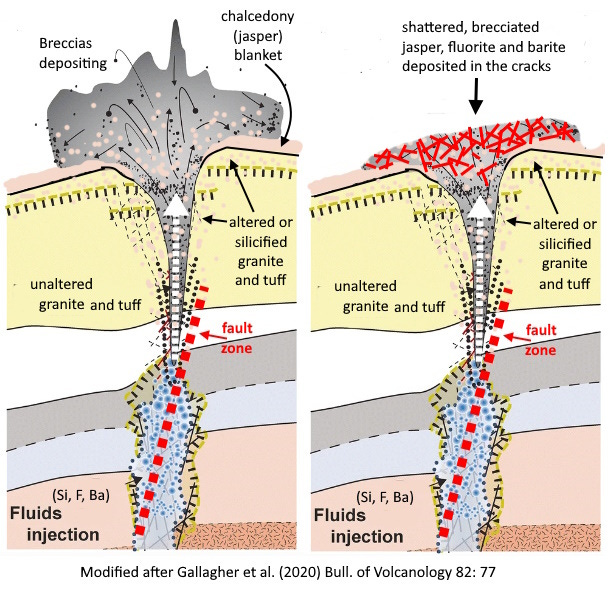

From other rocks in the vicinity that are shattered (brecciated) and re-cemented, we know that in places the cracks completely disrupted the rocks. But for the piece in the photo at the top of this page, the crack must have formed but not separated the two sides very far before the barite was deposited in it.

This is an unusual form for barite at this location. More often it forms complete, discrete crystals growing on an irregular substrate, often on all sides of obviously broken rocks, so it must have been deposited late in the overall process in relatively wide open spaces. From other nearby rocks, we know there was a slightly earlier period in which the mineral fluorite was deposited on the substrate before the barite was, and both were deposited after layers of jasper, iron-rich chalcedony (fine-grained quartz) were deposited on the substrate of volcanic tuff.

The fluorite and barite were probably deposited in an explosive hot spring that both shattered the rocks and deposited the minerals in the cracks. Best guess is that it might have been associated with relatively recent faulting – the nearby Rocker Fault was probably active around 5 million years ago and possibly as recently as 1.8 million (Elliott & McDonald, 2009, Geologic Map and Geohazard Assessment of Silver Bow County, Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open-File Report 585).

Excellent!