There are two forms of rose quartz, apparently with quite different modes of formation. Massive material is colored by microscopic (or submicroscopic) inclusions of some borosilicate mineral, while nice crystals of rose quartz are tinted because of color centers with aluminum ions and phosphorous replacing some silica, stimulated by natural irradiation in a manner similar to that of smoky quartz.

Here’s something that does not seem to fit either of those modes.

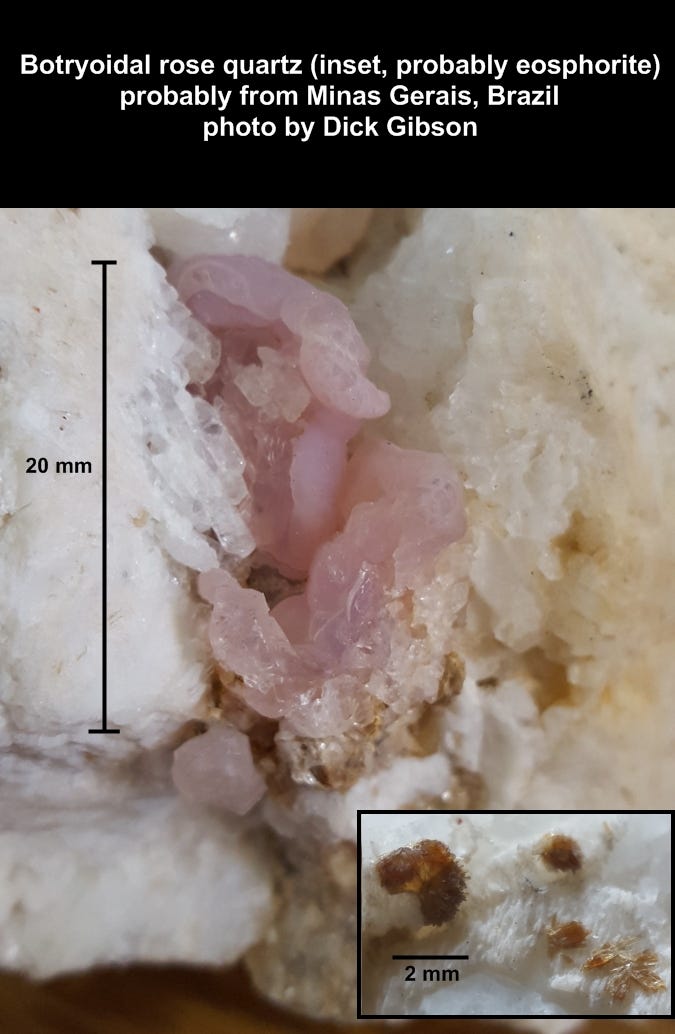

This botryoidal, almost vermiform (worm-like) rose quartz is probably from Brazil. Its association with tiny sprays of eosphorite (hydrous manganese aluminum phosphate) suggest that it is probably from Taquaral in Minas Gerais, because the vast majority of 100+ images on MinDat are from there. There is a slight possibility it is from a similar pegmatite in Maine USA, but I doubt it. The specimen belonged to my mineralogy professor Carl Beck, and I’ve had it since 1971.

Hardness and luster are very quartz-like, but this has not been analyzed. I’m sure it’s not the phosphates strengite or hureaulite, which are much softer.

Botryoidal (from a Greek word for “a bunch of grapes”) quartz isn’t very unusual, especially in the form of chalcedony, sub-microscopic aggregates of quartz crystals that are often colored by inclusions to make varieties such as agate, jasper, and many others. The word “chalcedony” gets used for lots of things, sometimes beyond the strict definition.

I’m pretty sure this is not pink chalcedony, nor another alternative, very pale amethyst. Botryoidal amethyst certainly does exist, famously as purple masses of spherules from Indonesia. So I’m sticking with “botryoidal rose quartz” for now.

The substrate is albite var. cleavelandite.

The pegmatites around Taquaral are attributed to collisions that assembled the cratons of Brazil, called the Araçuaí Orogeny (Pedrosa-Soares and others, 2009, Field Trip Guide, Eastern Brazilian Pegmatite Province: 4th International Symposium on Granitic Pegmatites). This was about 600 to 500 million years ago (Neoproterozoic to Cambrian) and I’d call it an aspect of the Pan-African Orogeny that brought many small blocks together to form the supercontinent Gondwana.

As soon as we think we can ID something because we 'know what it looks like,' we run into an exception! The diversity is awe inspiring. ( And sometimes annoying.).

Thanks for the column, Richard.