Tin

It isn't just for cans anymore

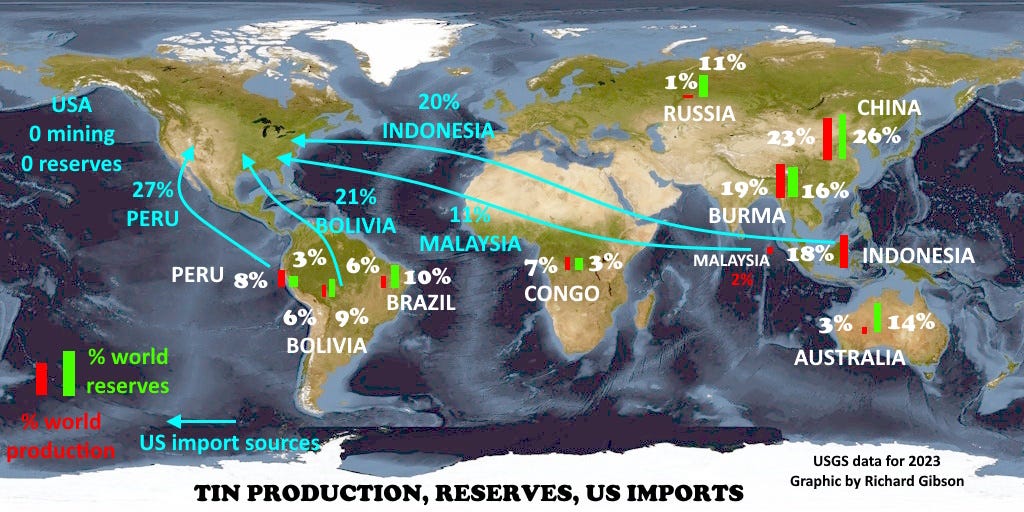

Tin is one of the critical minerals listed by the US Geological Survey, but we don’t have any. At least not in economic concentrations. The US has not mined tin since 1993, and today the USGS says US reserves of tin are “insignificant,” although some deposits in Alaska have been evaluated in the past 15 years or so. Peru, Bolivia, and Indonesia are the primary suppliers of imported tin to the US, but thanks to recycling, which accounts for about 25% of US tin consumption, the US is only about 75% dependent on imports (ranging from 74% to 81% in the past five years).

Tin was known in ancient times, probably at least 5000 years ago as tin was alloyed with copper to make bronze. The word “tin” is from Germanic, but the Latin name, stannum (source of the element’s chemical symbol, Sn), is ultimately possibly pre-Indo-European. Alternatively, a prominent German encyclopedia, the Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, suggests that stannum is from Cornish stean, tin, but I don’t think it is clear which way the word evolution went.

There are many tin minerals, but only one, cassiterite, tin oxide, is a significant ore. That name is from the Greek word kassiteros, for tin, derived from Phoenician cassiterid or cassiterides, their name for the then semi-mythical islands of Great Britain and Ireland. Cassiterite from Cornwall, England, exploited at least 4,000 years ago, was a primary source of tin for the Phoenicians for bronze.

“As of old Phoenician men, to the Tin Isles sailing

Straight against the sunset and the edges of the earth,

Chaunted loud above the storm and the strange sea's wailing,

Legends of their people and the land that gave them birth…”

― C.S. Lewis, Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics

Historically, the world’s greatest producers of tin have been Malaya (Malaysia) and Bolivia, and tin was Bolivia’s primary export for most of the 20th Century. Both nations have dropped below other producers today, as shown by the red bars (production) in the map at the top. For my specimen below, I only have “Bolivia” as the locality, but it’s quite likely to be from the Viloco Mine, one of the most prolific producers of both ore and specimen-grade pieces.

In the US, the largest fraction of tin (23% in 2023) is used in tinplate, a coating for steel analogous to galvanizing (with zinc) to reduce corrosion. Tinplate also goes to true tin cans (actually steel coated with tin), although aluminum and aluminum-magnesium alloys are more common today. Solder, usually a tin-lead alloy, takes 11% of the tin used in the US, making tin the most voluminous metal purchased by the Apple Corporation for the tiny amounts used in solders for a great many electronic products.

Tin chemicals in things from toothpaste (stannous fluoride) to two-liter beverage bottles (where organotins make the plastic stronger and scratch resistant) use tin in total volumes comparable to tinplate. Other forms of packaging, perfumes, and pesticides use tin, and plate glass is typically made flat by pouring molten glass onto a bed of molten tin. Collapsible metal tubes are sometimes tin-based alloys.

Babbitt metal alloys of tin, lead, copper, and antimony are the best metals for strong bearings such as those used in automotive applications. Similar tin-lead-antimony alloys in pewter and type metal have largely been replaced by other compounds and technologies.

Based in part and updated from my book, What Things Are Made Of.

Tin caughty attention from the beginning of my collecting. Its just cool.

I saw one gem cassiterite cut for a ring but it was too narrow for me. I regret not buying it now...I want to wear a ring and tell people " that's what tin comes from.". I've not seen another since. Probably too pricey now.

Thanks for the article Richard.