Tiny Treasure

A new acquisition

I recently acquired a pile of unsorted, unidentified, unlabeled specimens from my friend mineral dealer Paul Senn. All were from an old collection of material from the Black Pine Mine near Philipsburg, Montana.

Most of the pieces (176 of them) are micromount size, which is fine with me – I very much enjoy exploring the tiny things, looking for that one bit of some weird mineral that’s unexpected. For me the two-centimeter quartz crystal at the top of this post is the star of the micro-show, among many other nice and interesting specimens.

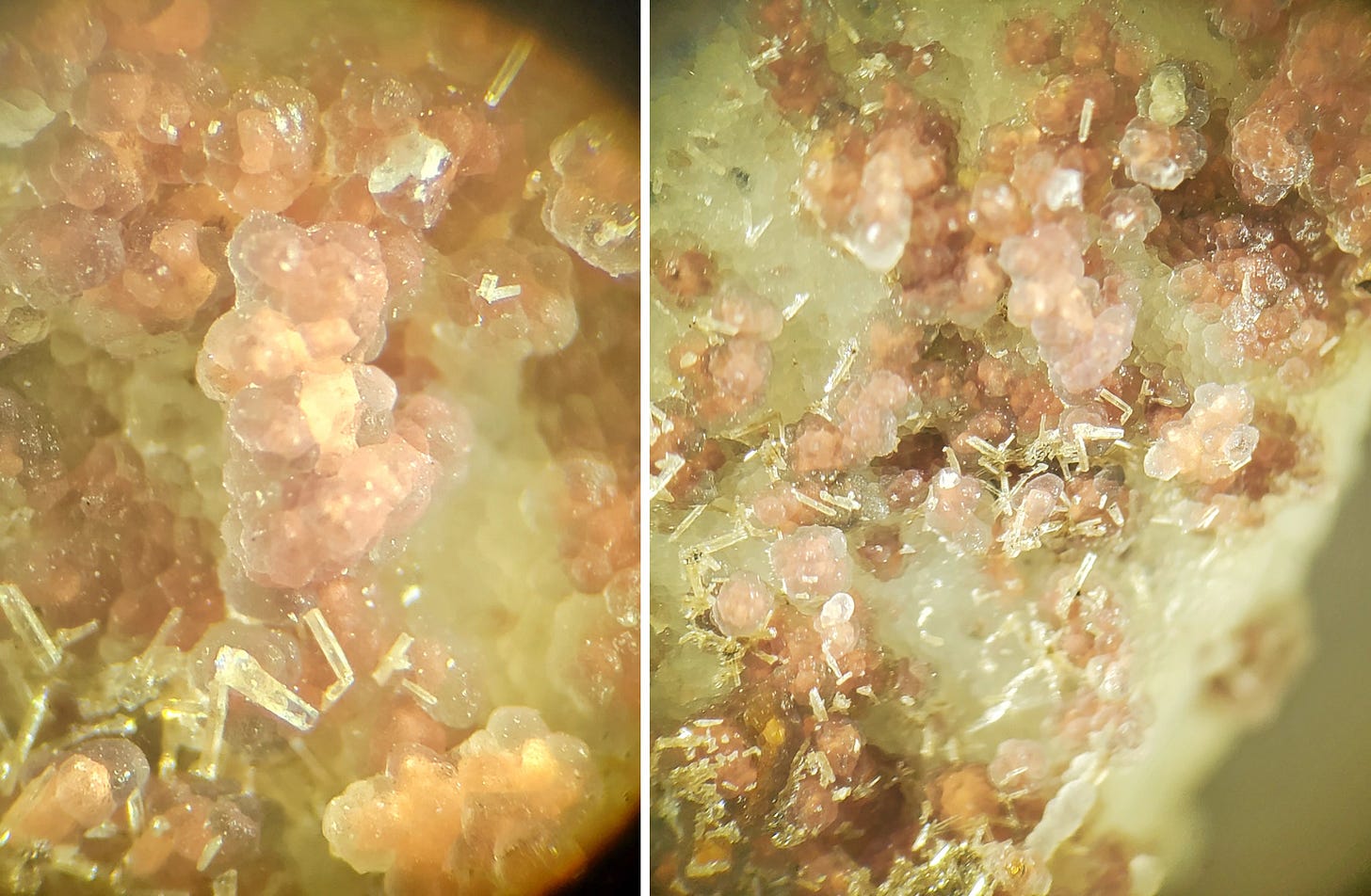

It may look like quartz suffering from bubonic plague or some other disease, but microscopically, the reddish ‘pustules’ are revealed to be botryoidal, almost transparent chalcedony encrusting grains and sprays of native copper.

I can’t quite capture the metallic flash of the copper through the coating of chalcedony, but I’m sure it’s copper. In a few tiny spots where a break reveals the copper, it’s altered black (probably to cuprite or tenorite, copper oxides) with hints of green, which at Black Pine could be any of many copper arsenates, sulfates, phosphates, and carbonates. And in another specimen, similar grains and sprays of copper on quartz are uncoated by chalcedony.

The final aspect that makes this a fascinating piece is tiny little white sticks of pyromorphite (lead phosphate chloride). They are scattered on the chalcedony, mostly just on one of the quartz prism faces. A few of the pyromorphite crystals are close to a millimeter long, but most are smaller, right at the limit of my microphotography skills without a lot more work (which I’ll probably try to do later).

Black Pine was a major producer of lead, zinc, and copper, and is famous among mineral collectors for an exotic suite of minerals including many rare copper-lead-zinc arsenates and phosphates, especially world-class examples of veszelyite, a deep blue copper-zinc phosphate.

Over time the Black Pine Mine produced about 5,600,000 ounces of silver, 3,000 ounces of gold, and more than 100,000 tons of lead (for comparison, the Butte district produced about 750,000,000 ounces of silver, almost 3 million ounces of gold, and 430,000 tons of lead). The mineralization is in hydrothermal veins and open cracks hosted in the Precambrian Belt Mount Shields Formation and related strata, and the hot fluids probably came from igneous intrusives generally related to the granitic Philipsburg Batholith, intruded about 75 million years ago (Naibert and others, 2010, LITHOSPHERE, v. 2, no. 5, p. 303–327). The mineralization at Black Pine may be related to the small Henderson and Willow Creek Stocks, with the former dated to about 70 million years old and associated with thrust faults (Waisman, 1992, Mineralogical Record Vol. 23).

Although the host rock is Precambrian Belt strata, the phosphorus to generate the phosphates likely came from the Permian Phosphoria Formation, which crops out within about 5 miles (and is likely present in the subsurface in the lower plate of a thrust fault) and through which the mineralizing fluids probably passed. Phosphate rock often has elevated arsenic concentrations as well, so the Phosphoria might be the ultimate source for some of the very weird arsenates and phosphates at Black Pine.

Getting into the supermacro photography can be very rewarding 😁

Rich, I enjoyed reading this!