Traces

“Covered now with lines and creases”

Ichnology (from Greek ἴχνος, ikhnos, "trace, track") is the study of trace fossils, tracks, borings, and other features created by living organisms preserved in the rock record, but sometimes (even usually) with no direct evidence of the critter that made the marks.

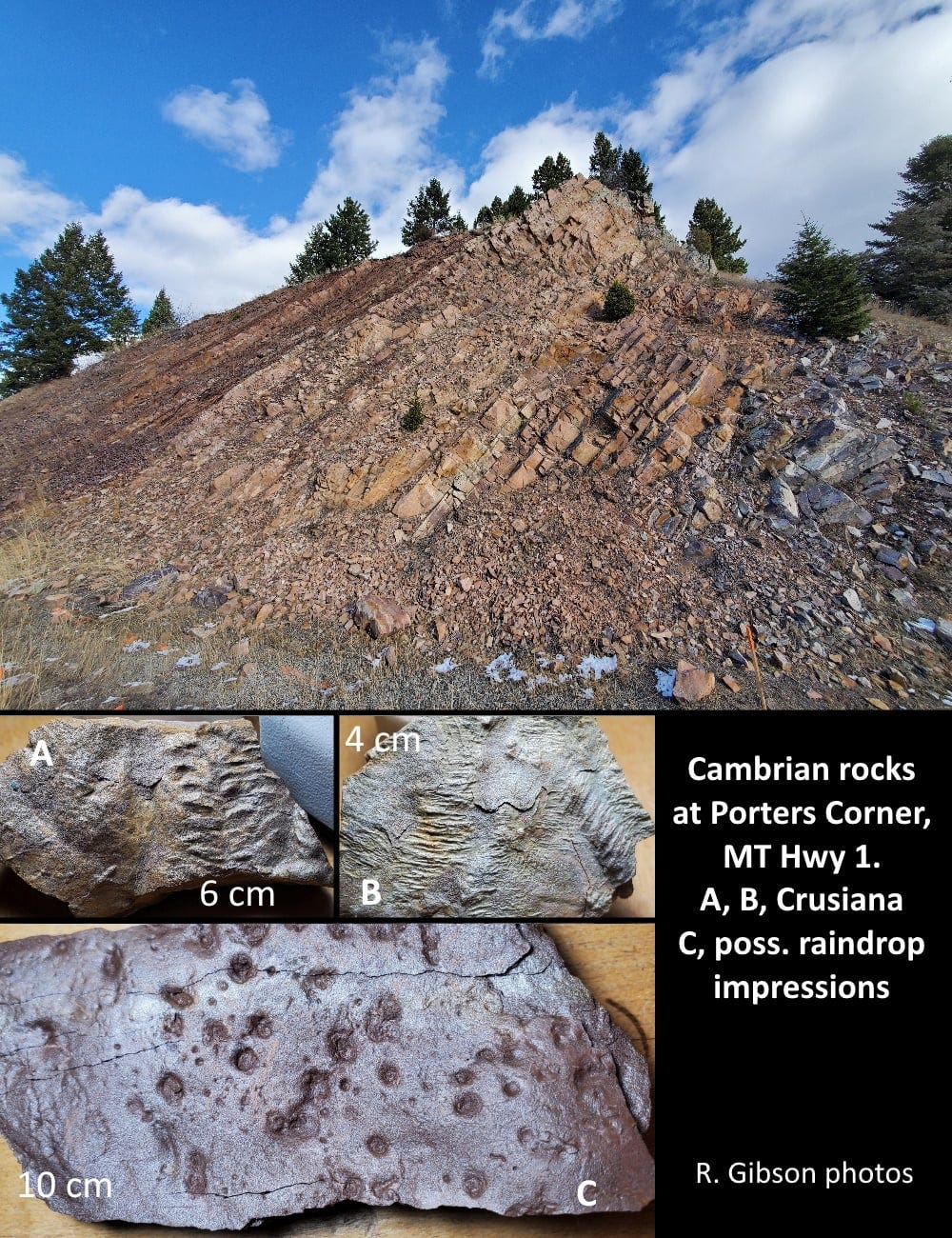

Montana rocks preserve lots of trace fossils. In the shallow-water mud of the Cambrian Flathead and Wolsey Formations, life was abundant about 515 million years ago. We know from body fossils (and glauconite, iron phosphate, pellets derived from their poop) that there were many trilobites present. One form of common trace fossil, crusiana, is often interpreted as trackways of trilobites, but some workers consider them to be feeding marks of worms (or trilobites). They tend to be somewhat elongate and often show paired sets of marks.

It's been suggested that they are Diplocraterion, which is a burrow with successive crescents of infilled sediment as the animal in the burrow adjusted its position to a specific depth. But my understanding is that Diplocraterion is a vertical burrow and these features are definitely on horizontal bedding surfaces.

The Cambrian Wolsey Shale shows that in places its original mud was seriously churned up (“bioturbated”) by something, most likely worms burrowing just beneath the surface to ingest the mud and filter out food particles. Sometimes the burrows are tiny and almost pervasive in the rock, like the photo at right, but in places the burrows may be considerably larger like those at left. The large burrows probably survived as the rock lithified because the material filling them (either as the animal passed though and “back-filled” the burrow, or filled later by sediment) was slightly different in texture – size, composition, water content, compaction – from the surrounding mud and silt.

Like most scientists, specialists in trace fossils attempt to categorize them according to their geometry or purpose. Burrows like these in the Wolsey would probably be called Fodinichnia, three-dimensional structures (but in this case generally horizontal more than vertical) left by animals which eat their way through sediment, such as deposit feeders, but as a non-specialist I just call them burrows and bioturbation.

The Mississippian Period (Lower Carboniferous, around 330 million years ago) was another time of shallow, warm seas in Montana, rich with life. The Lodgepole Formation of the Mississippian Madison Group contains lots of body fossils of corals, bryozoans, crinoids, brachiopods, and gastropods that clearly lived in close proximity. All those animals secreted hard calcareous parts, and their abundance probably contributed to the calcium carbonate in the water that ultimately became the Lodgepole Limestone. As always, it’s much more challenging to find evidence for the soft-bodied organisms such as worms and plants that must have also been present.

I learned to call the specimen above teonuris. That’s a word that’s no longer used (Google only finds it in my History of the Earth blog), and now I think these marks would be considered to be the arcuate, side-to-side feeding traces of some kind of worm. The general category for such features is Pascichnia, and they are similar to the arcuate marks called Zoophycos. When I learned about them (and collected this piece) in 1969, they were interpreted as the marks left by plants fixed on the marine water bottom, swirling around and scouring the mud surface nearby.

The alternating gray and buff colors represent slightly siltier (buff) zones in the gray limestone.

The Permian Phosphoria formation (about 280 million years ago) of Montana contains lots of near-vertical burrows, generally referred to the species Skolithos grandis in the broader categories Fodinichnia (feeding burrows) and Domichnia, burrows for living (Andersson, 1982, Permian trace fossils of western Wyoming and southwestern Montana: Systematics, paleoenvironment, and diagenesis: U. of Wyoming Ph.D. dissertation). In some places, they were filled later by sand in surrounding chert (fine-grained silica), and in others they may be more chert filling in a burrow in what is now sand. They can reach 5 cm or more across and typically show the irregular scoured side features and “knee-bends” which may (or may not) reflect the animal’s activity in excavating the burrow or living in it.

As far as I know there is no evidence for what the animal was. It might have been something like the modern geoduck burrowing clam, but that’s entirely speculation.

My last example of Montana trace fossils represents one life form exploiting another after death during the Jurassic, around 160 million years ago. The Jurassic sea in Montana supported many belemnites, extinct squid-like cephalopods. The fossil isn’t the whole animal by any means – it’s just the most commonly preserved part, an internal structure called a guard (or rostrum) that probably served as a counterbalance for the animal and helped it swim. It was probably made of calcite or aragonite (both are calcium carbonate, but with different crystallography) in life and is calcite or aragonite in fossils.

The marks on the belemnite guard in the photo above are trace fossils called Rogerella, the borings left by a barnacle which drilled into the guard, certainly after the belemnite’s death since the guard was inside the belemnite and surrounded by muscular tissue during life. The barnacles lived in the elliptical openings. They would have been really small barnacles, since these openings are rarely longer than a millimeter. Unlike the belemnites, which died off in the end-Cretaceous extinction, the acrothoracican barnacles that made these borings survived as a group and can be found on shells in oceans today.