Like most of the great rivers of the world, the Amazon isn’t where it is by accident. Underlying tectonic features control its location.

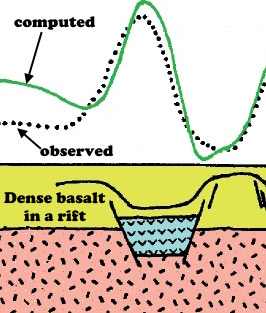

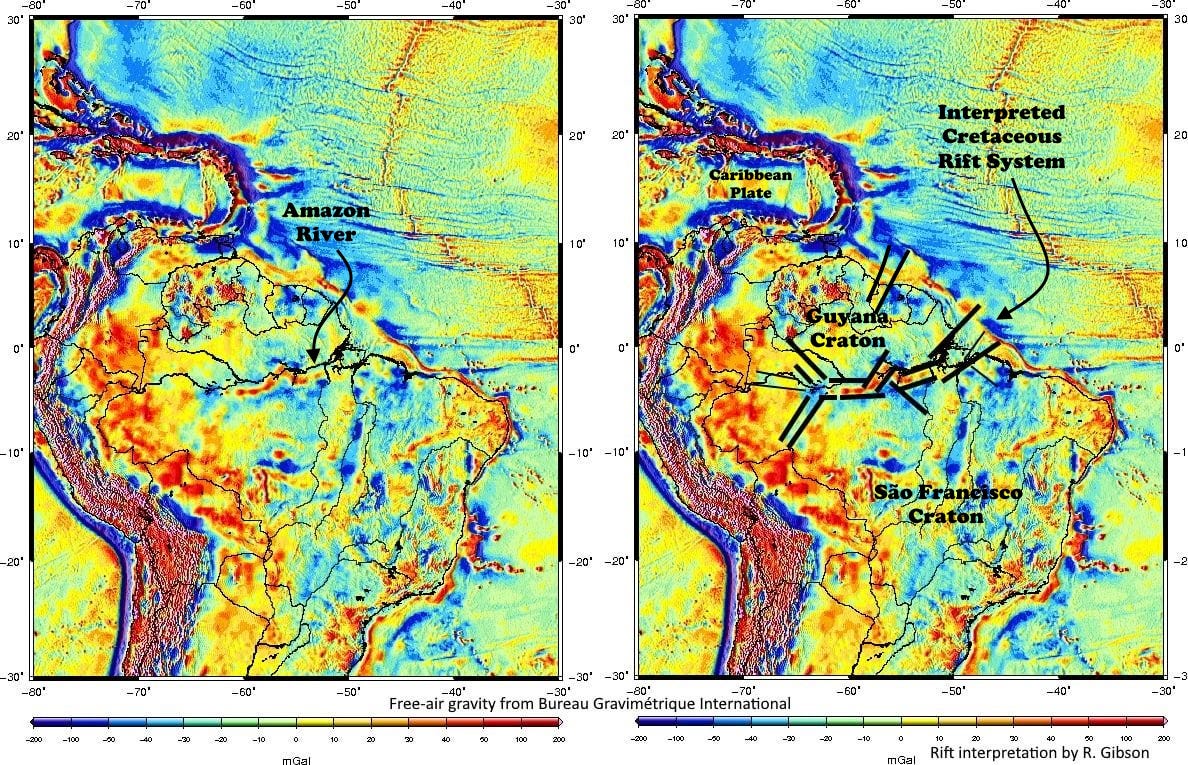

The gravity map of South America shown here (extracted from the world free-air gravity map from the Bureau Gravimétrique International) shows a more or less linear, narrow gravity high (red) pretty much right along the Amazon River in the jungle of northern Brazil. Although it has a notable kink in it, this linear, narrow gravity anomaly is the expression of interconnected troughs filled with dense material – in this case, a fault-bounded rift containing a lot of dense basalt.

The Amazon Rift’s heritage probably dates to fault zones created when the West African craton amalgamated with the Guyana and São Francisco Cratons in South America, part of the formation of the supercontinent of Gondwana called the Pan-African Orogeny, about 510 million years ago (Burke and Lytwyn, 1993, Origin of the Rift Under the Amazon Basin as a Result of Continental Collision During Pan-African Time: International Geology Review, 35:10, p. 881–897).

More important to the region for the development of the Amazon River basin was a rejuvenation of these faults as a pull-apart rift when the central and south Atlantic Ocean began to develop about 115 million years ago. As the northeastern coast of what is now South America began to slide away from the present-day southern coast of West Africa (Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria), the interior of the continent also broke along the old Amazon fault zones. The overall plate motions made this area pull apart enough for basalt to erupt and fill the fault-bounded troughs.

It’s correct to think of this zone as a location where South America “tried” to rift apart. If the Amazon Rift had not failed, South America north of the Amazon might have remained attached to (or at least much closer to) North America, while South America to the south might have taken off in a somewhat different direction. There would have been an ocean where the Amazon River lies today, and the Caribbean Sea would probably have never developed. But it did fail, and South America remained in one piece, albeit a little stretched there where the Amazon River flows today. There is little or no surface expression of the old rift other than the existence of the Amazon River basin itself.

There was probably some kind of west-flowing river system across what is now northern South America from soon after the Pan-African Orogeny 550-600 million years ago when the area around the present-day Amazon mouth was mountainous, suggested in the cartoon above. The next (or continuing development of) Amazon River still flowed west into the Pacific from its beginning about 115 million years ago, when the borderland between what is now Africa and South America was a highland. Even after the Atlantic rift began to form, relatively high rift shoulders probably kept the early Amazon flowing westward until the Andes began to rise at rates that exceeded the river’s ability to cut down through the mountains, probably in Miocene time about 15 to 20 million years ago (Russell Mapes, 2009, Past and present provenance of the Amazon River, PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). Even today, there are fresh-water stingrays in the Amazon basin whose closest relatives live in the Pacific. Thus the modern Amazon River is less than about 10-15 million years old even though its heritage dates to more than 500 million years ago.

The interpreted version of the map, at right in the top image, shows an arm-waving idea of some of the faults (black lines) that define the Amazon Rift system. The basalt flows that create the gravity highs in the rift are probably Cretaceous in age, coeval with the opening of the Atlantic, but some aspects of the gravity highs in the rift may be older, Cambrian or Ordovician. Dense pyroxenite was encountered in a well drilled on the gravity anomaly in 1962 and dated to about 400 million years ago (Szatmari, 1983, Amazon rift and Pisco-Juruá fault: Their relation to the separation of North America from Gondwana: Geology 11:5). That date is unexpectedly young – we’d expect the Pan-African Orogeny and its related intrusive and volcanic rocks to be more like 500-650 million years old.

Free-air gravity data are measurements that account only for the distance between the gravity meter and the center of the earth, which is to say elevation, as if measured in nothing but free air. It does not take into account topography, bathymetry, or the background density of the earth’s crust and mantle, so consequently things like mountain ranges overwhelm the signature (as you can see with the Andes on these maps, and likewise strong bathymetric effects like oceanic trenches overwhelm the gravity signature). Free-air data are most informative of geology in places where the topography is relatively flat, like the Amazon Basin – the result is then essentially a map showing dense rocks and less-dense rocks.

very cool; thanks