Happy Holidays of all sorts to all who celebrate. And thanks to all the readers of The Geologic Column – and a special thanks to the donors! I appreciate all of you very much.

There’s not much geology in today’s post, but I hope you enjoy this look at an early mining camp, written as part of my “other” life, as a Butte historian.

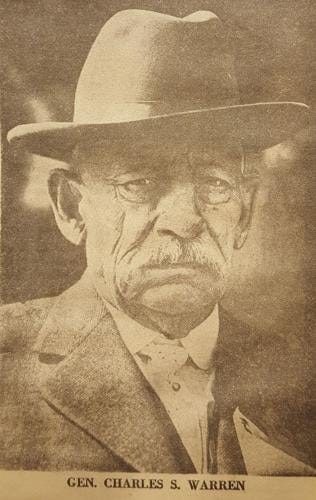

The winter of 1866-67 was a cold one in Butte. Actually, there wasn’t much “Butte” – the population as recalled by pioneer Charles S. Warren was fewer than 200, but the placer gold camp at Silver Bow City about 6 miles (9 km) down the creek from Butte still had perhaps 2,500 people, including “not more than 25 women and children,” according to Warren.

One of those women in Silver Bow City was Mrs. H.A. Price, who ran the only restaurant. She was doing well with meals at $1.50, but for Christmas dinner 1866, she charged $2.50 (payable in gold dust) for a spread of rabbit and elk meat, but no turkey, and her traditional English Christmas specialty, plum duff, was a failure. But there were other treats available, for a premium price: A dish of sauerkraut from Salt Lake City for a dollar extra, or a boiled onion for 25 cents.

In the photo above looking east toward Butte (out of sight at far left), Silver Bow City stood where the road, railroads, and Silver Bow Creek pass under the interstate overpass in the middle left distance. The only survivor is the Silver Bow Brewery malt house, at the far left edge of the photo (now a private residence). The first gold discovery in the area around Butte, in 1864, was in the creek near its bend, north of Sherman Butte that’s seen on the right part of the photo. That bend may be the curve that glinted in the sun and gave the first prospectors the inspiration to call it Silver Bow Creek.

Most of the miners were out of work for the winter of 1866-67, and a frigid Christmas week was spent with fires in the street and general “jollification,” even when the thermometers that were good to 40 below froze solid on New Year’s Eve. The spring of 1867 was no better, and Warren recalled that Eddy & McMahan’s Silver Bow Saloon could not open on March 15 because “every drop of whiskey was frozen.” As much as 10 feet of snow was still on the ground at Silver Bow City on June 1.

Charles Warren, born in Illinois in 1847, became one of Butte’s early, if less remembered pioneers. He partnered with William Clark in the Black Rock Lode in 1880 and with Charles Mussigbrod in the Cossack, but he sold his interest in the Lexington to A.J. Davis for $50 or less – and Davis sold it a few years later for more than $1,000,000.

Following a short stint as Sheriff of Deer Lodge County in 1873, Warren became the first police magistrate in Butte about 1879. He invested with Lee Mantle in the Silver Bow Electric Company, the Inter-Mountain Newspaper, and was one of the founders of the Electric Street Railway in 1890, when a fare was 10 cents (which was to be reduced to 5 cents after the first five years).

Warren’s fortune allowed him to become a charter member and first president of the elite Silver Bow Club. In 1872, he and his wife Mittie were among the first to be married in Montana Territory. Their Butte home was at 211 South Washington, a near neighbor to internationally known Black singer Robert Logan, who sang at Warren’s funeral in 1921. Warren Island in Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho, is named for him.

My Dad reported a bit of wisdom related to him, from the days of horse drawn transportation. In those days, in the winter, the drivers of buggies and maybe sleighs would gather to pass the time, outside the venue to which they had transported their employers. Strong drink was the favored libation, but it could not be kept on one’s person. Concealing it somewhere on the coach was a possibility except a quick shot of 40 below whiskey could cause interior frostbite. Somewhere within the harness of the horse was ideal. I don’t know harness well enough to say exactly, where. On a pack animal, it would be between the saddle and the blanket, where the horse would keep it warm.

Merry Christmas, Richard