Y is for Yosemite

The Sierra Nevada Batholith

Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

August 1973 was the month I and my friend Steve both turned 25 years old, and we celebrated with our first backpacking adventure. The trail to Young Lakes, above Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park, California, is an easy 6.5 miles (10.5 km) each way with about 1,389 feet (423 m) of gain, but it was interesting enough for two easterners (I had lived in Davis, California, for a year, but for most purposes I was still a tenderfoot Midwesterner).

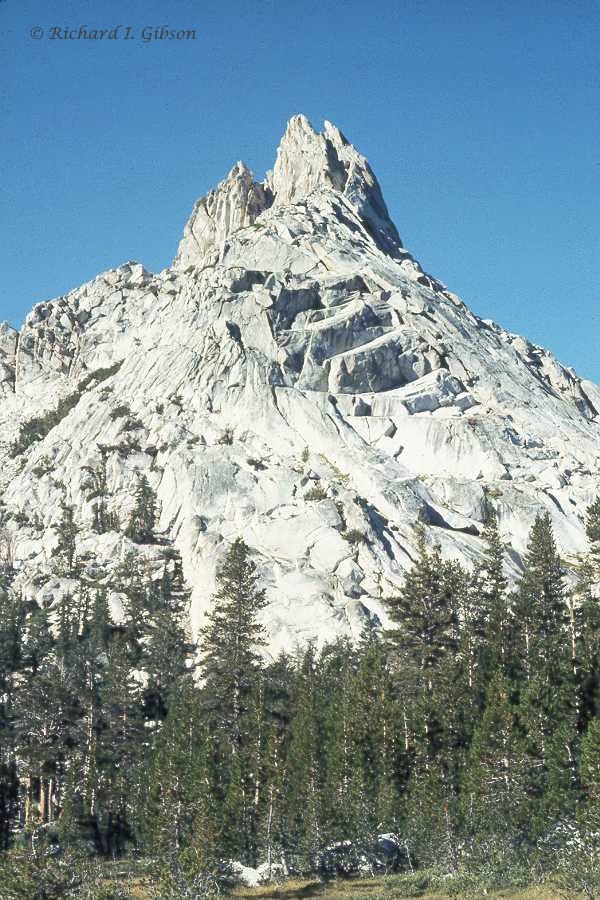

The reward of that hike is Ragged Peak, in the photo at top. Young Lakes sit at 9,880 feet (3,010 m) and Ragged Peak has an elevation of 10,917 ft (3,328 m). I recall no one else on the trail in 1973, but now you need a permit and probably have to stand in line for it.

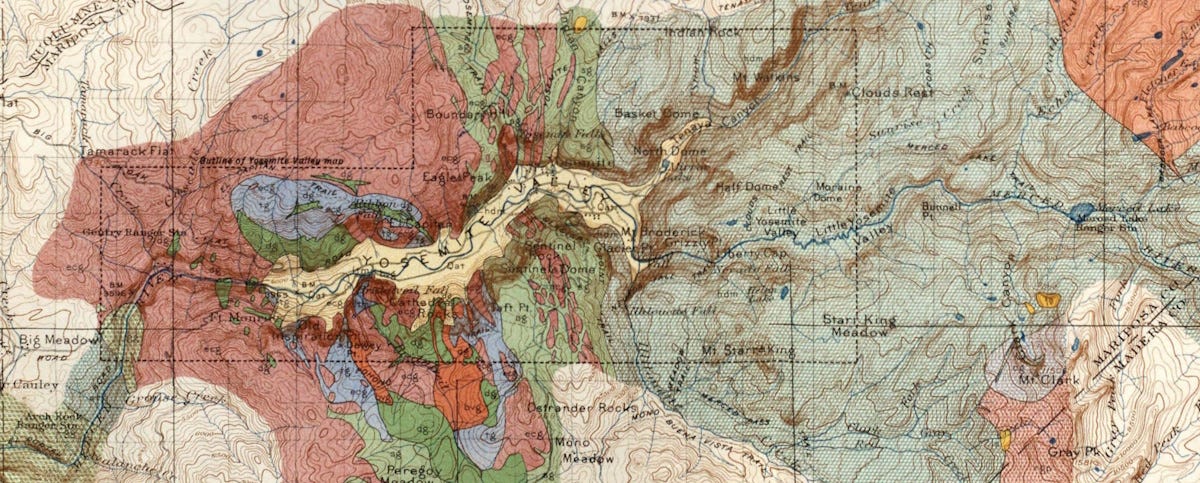

Most of the rocks in Yosemite, including most that you see in these photos, are granites and similar rocks, formed as a result of standard but long-lived subduction of the Farallon Plate beneath western North America, mostly about 105 to 84 million years ago, but probably beginning as early as 175 million years ago (Jurassic; more information in this History of the Earth Calendar podcast episode) with some ongoing intrusions for millions of years later. The batholith is not one single blob of granite but is a composite of many individual bodies as you see in the multiple colors of the map above, like an amalgamation of the various blobs of material in a lava lamp. Even the Boulder Batholith in Montana is something like 15 or 16 such blobs, and it is much smaller than the Sierra Nevada Batholith.

The Sierra Nevada Batholith is close to 650 km (400 miles) long and 110 km (70 miles) wide, a long linear belt that coincides fairly well with the modern Sierra Nevada mountain range. That coincidence isn’t entirely an accident. The huge composite block of granite probably served as a rigid element of the crust, guiding later breaking. The east front of the Sierra is more or less a continuous suite of related faults that lift the range up relative to the country to the east, where stretching has broken the crust and formed the basin and range in Nevada and western Utah and adjacent areas.

It was dry in California that August 52 years ago, when I took the photo of Yosemite Falls above, with very little flow. The total drop is 2,425 feet (739 m), but the upper fall, seen here, is 1,430 feet (440 m).

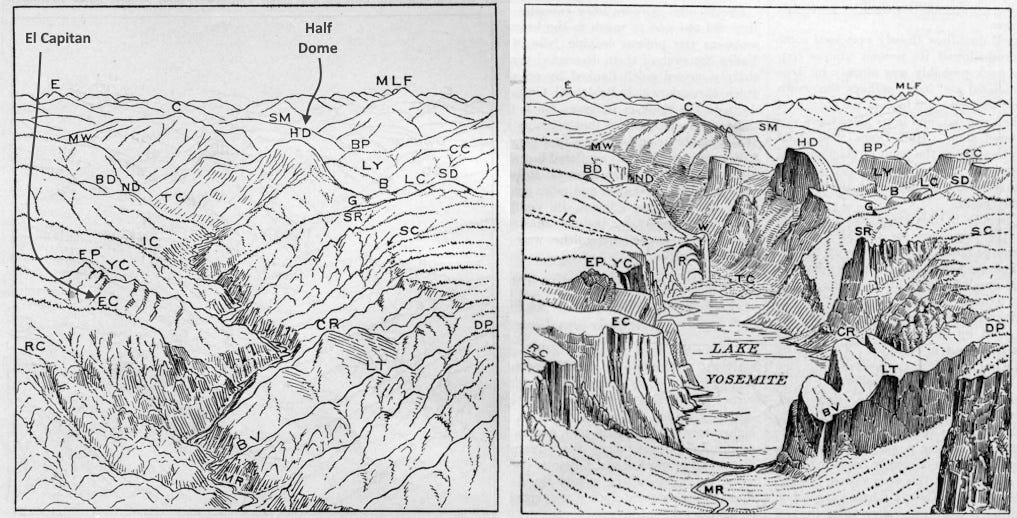

Yosemite Valley with its near-vertical walls that lend themselves to waterfalls was carved in just the past two million years or so by glaciers. A large valley glacier exploited an old weak zone that had been occupied by a fairly deep stream valley (on the left in the drawings above), and carved a steep-walled U-shaped valley. Soon after the glaciers melted, around 12,000 to 18,000 years ago, the floor of Yosemite Valley was occupied by a lake dammed by a glacial debris pile (a moraine), and much of the valley floor is flat because of the lake deposits that formed there. So it lacks the classic U-shaped valley of glaciers – except it really is U-shaped beneath those late-deposited lake beds. Continual downcutting by glacial meltwater eventually allowed the lake to drain, so the Merced River, fed by the water of Yosemite Falls and others, now flows through Yosemite Valley.

“After ten years of wandering and wondering in the heart of it, rejoicing in its glorious floods of light, the white beams of the morning streaming through the passes, the noonday radiance on the crystal rocks, the flush of alpenglow, and the irised spray of countless waterfalls, it still seems above all others the range of light.”

— John Muir

Mount Conness (12,590 feet; 3,840 m), near Young Lakes, was named for John Conness, native of Ireland and a U.S. Senator from California who was crucial in passing the 1864 Yosemite Grant Act that protected Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove. In 1864, geologist Clarence King, the first to ascend the peak (with surveyor James T. Gardiner), suggested it be named for Conness.

Yosemite is derived from yohhe’meti, “they are killers” in the Miwok language. It historically referred to the name that the Miwok gave to the Ahwahneechee, the resident indigenous tribe. Previously, the region had been called Ahwahnee (”big mouth”) by the Ahwahneechee. The term Yosemite in Miwok is easily confused with a similar term for “grizzly bear,” and is still a common misconception. (From Wikipedia)

My Dad took us backpacking in the Sierras as kids. Being the youngest of 3, I had to wait till I was 11 before I was allowed to go. Then, each summer I joined him and my siblings and others deemed worthy (my mother, my best friend). It gave me one of my first fascinations with geology- my dad explained glaciers to me and we observed glacial polish, striations and U-shaped valleys. There's a rock quarry near Mariposa that mines a very white granite for building stone. It's really amazing how variable those little stocks are. [I finally upgraded my back pack about 10 years ago]. Cora