Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

The name of the place says it all: Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park. But for me, it’s one of those places where the experience is vastly better than a description or a photo. Nonetheless, here are some photos of this place in southern Utah USA.

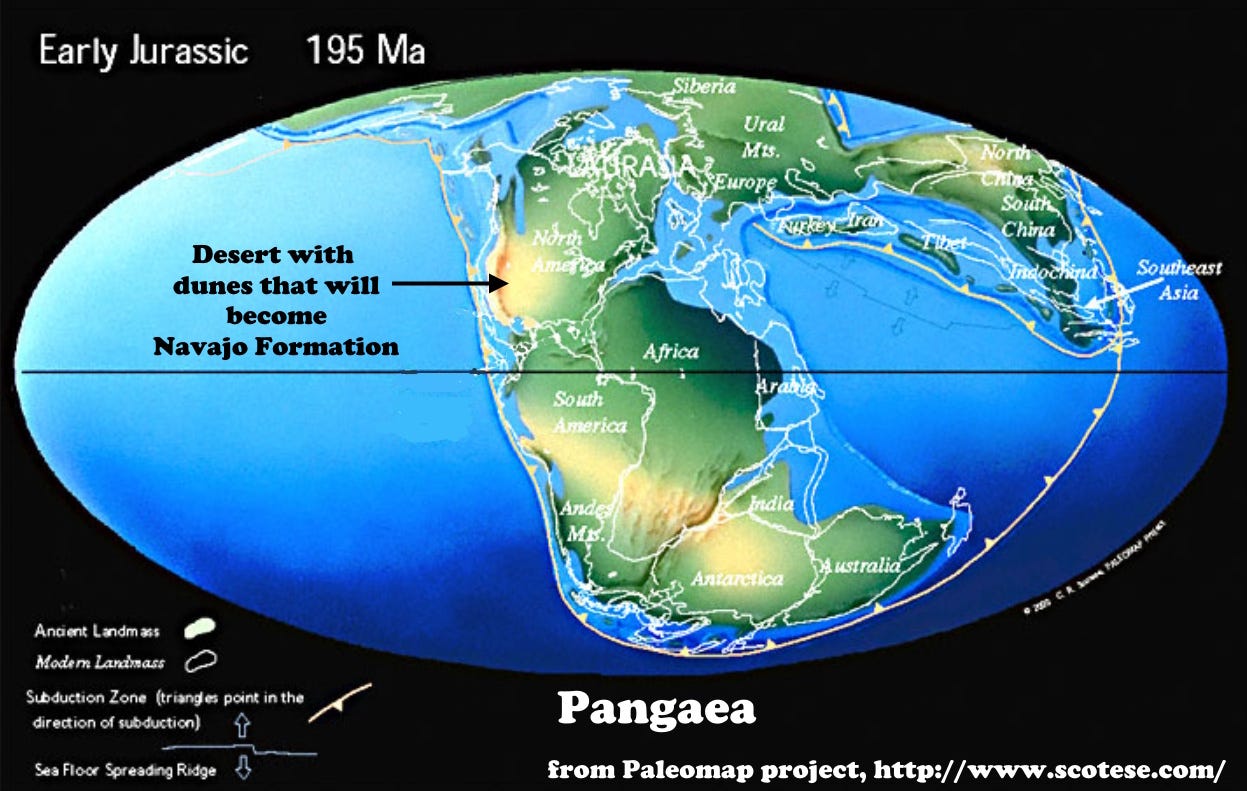

The sand eroded from outcrops of the early Jurassic Navajo Sandstone (and some other sandstone units), which was deposited in an extensive desert about 201 to 195 million years ago, in the western part of the supercontinent of Pangaea. Today, the Navajo Sandstone shows a wide range of colors, from white and gray to prominent reds, pinks, and purples. The colors reflect variations in iron oxide content in the form of hematite, Fe2O3, essentially rust.

The iron was incorporated into the sandstone by groundwater percolating through the relatively porous sand and coating and cementing the individual grains of quartz, which themselves are colorless.

In some places, such as the Great White Throne in Zion National Park, the Navajo is white because it has been bleached by water without iron percolating through, dissolving and removing any hematite cement. Even there, patches of pink remain.

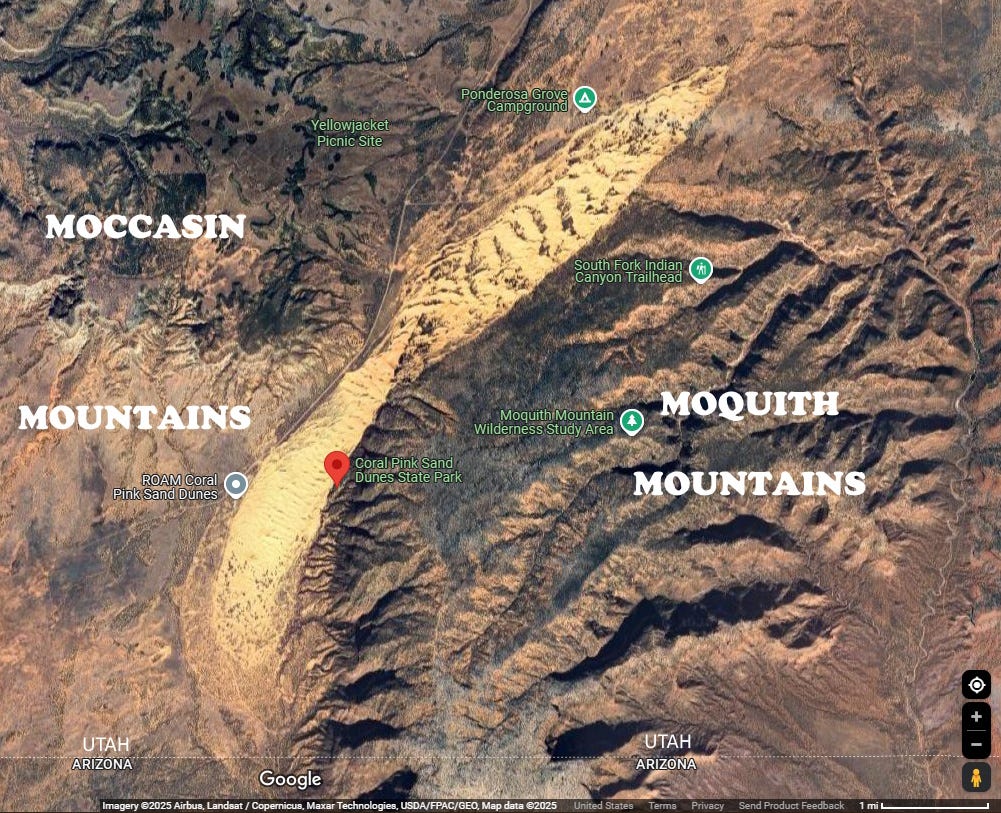

Normally, weathering would drop sand in a pile adjacent to cliffs, or it might be carried off in streams, but the Coral Pink Sand Dunes lie in a narrow notch between two mountain ranges (Moquith and Moccasin) where constricted wind speeds up enough to pick up the sand and then drop it when the wind speed falls beyond the notch, producing the dunes.

The dunes are not lifeless, but vegetation is sparse. Often the plants swirl in the wind, leaving curving tracks in the sand in the left photo above. At right is a similar mark in an ancient limestone (Mississippian age, about 330 million years ago, in Montana) which might have been made by a plant anchored to the sea floor and swirling around. Alternatively (and probably more likely), this might be a feeding trace of some marine animal filtering the sea-floor sediment. There’s more about trace fossils in this previous post.

Ah the Navajo Sandstone, my friend from the Canyonlands National Park. And sort of same as our New Red Sandstone here in SW Scotland. Microscope studies (I've read) quartz grain could have been sand then sandstone then sand again five or six times, is that so?

That was just a side trip we saw on our roadmap while touring Utah in 1976. Not as many visitors back then so we had the sand to ourselves. It's a wonderful place, so I'm happy to learn how and why those dunes are there, otherwise not common in canyon country.