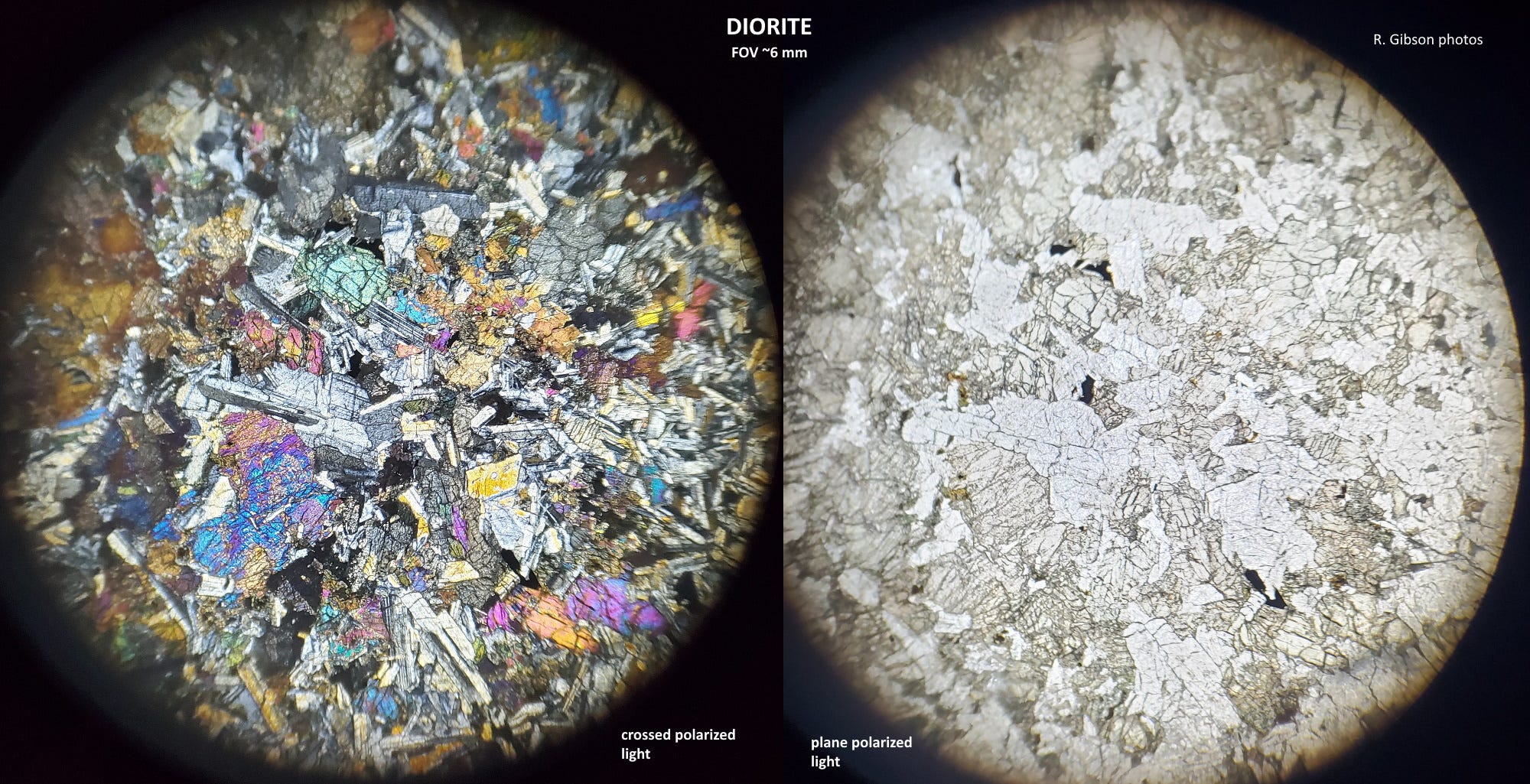

In the lapidary trade, these rocks are called “Chinese writing stones” or “daisy stones.” They are fine-grained diorite or andesite porphyry. Diorite (coarser) and andesite (finer) are essentially the same except for grain size; they are intermediate in composition between granite/rhyolite and gabbro/basalt. Porphyry means a rock has two grain sizes – in these cases, very very fine (the dark matrix) and quite large, the lath-like feldspar crystals. The big crystals grew down inside a magma chamber, then erupted in a mush with other molten material that crystallized quickly, forming the dark, fine-grained matrix. Without analysis, there’s really no good reason for me to say this is very fine-grained diorite or andesite versus basalt; basalt contains less quartz than the other two so it’s a composition difference more than texture.

The one on the right, which also has green epidote in it, is almost certainly from an igneous dike of likely Cretaceous age that was exposed during construction on Interstate 80 east of Auburn, California. I don’t know where the one on the left might be from, though possibly from another part of the same dike system. The two pieces are 10 and 14 mm long. Dikes near Auburn have been called diorite porphyry (Clark, 1954, The Cool-Cave Valley limestone deposits, El Dorado and Placer Counties, California: California Journal of Mines and Geology, Vol. 50, Nos. 3 and 4, p. 439-466) so let’s go with that for this rock.

The presence of epidote, Ca2(Al2Fe3+)[Si2O7][SiO4]O(OH), a calc-silicate mineral, suggests that there may have been some metasomatism (exchange of chemicals) between the igneous rock and whatever it intruded. That would make this perhaps a bit of a skarn, the rock that results from that chemical exchange. This would not be certain, but I’d say epidote is maybe more common as a skarn mineral or alteration than as a primary igneous mineral. Clark (1954, cited above) says the dikes at Auburn cut Carboniferous limestone, which would be a reasonable source for the calcium to make epidote.

Here’s your jargon of the day: these crystals are glomeroporphyrocrysts, which means they are crystals in a porphyry that have “glommed” together in clusters. The prefix glomero- is ultimately from Latin for “a ball of yarn.” You sometimes see this texture described as glomeroporphyroblastic, but the suffix -blast is usually applied only to crystals that grow in metamorphic rocks and I’m pretty sure these are igneous rocks, so I’m using -cryst. I knew you wanted to be able to use the terms properly.

OK, full disclosure, hardly anyone says “glomeroporphyroblastic” or “glomeroporphyrocryst” much these days; thankfully, the terms are obsolete, and diorite porphyry works just fine. We now return you to your regularly scheduled activities.

You can find a street named Porphyry here in Butte, Montana, where I live (at the corner of Quartz and Crystal), as well as in Ophir and Cripple Creek, Colorado. And in Seaham, New South Wales and Springsure, Queensland, Australia. Anyone know of others? For the etymology of porphyry, please see this previous post.

Of course I want to use those terms correctly, even if they are obsolete! You really scratch my itch with those photo micrographs. I loved optical mineralogy and miss spending hours looking thru a scope -- but I'm sure my neck and shoulders can't take the strain anymore.

Demonstrate that andesite is an igneous intrusive rock. I’ll wait.