I’ve never “discovered” a new mineral, finding it (and aware it was likely new), recognizing it, describing it, or any of those choices. But I have found some things, unknown at the time, that were later described as new minerals. Calderónite is one of them.

In the summer of 1971, I was a Teaching Assistant in the Indiana University geologic field course, G429, in Montana USA. For one of the final field mapping projects, I was assigned to what we called the Sacry’s Map Area, because it was largely on the land of the Sacry family south of Cardwell. The project extended onto some other land as well, including a jaunt northwest to the Mayflower Mine, largely to incorporate some important outcrops into the understanding of the whole area.

The old dumps of the mine had lots of rocks with lots of sparkly minerals, so of course I picked a lot of them up. As a naïve youngster, I figured the greens and blues were malachite and azurite, and the reds and pinks were iron oxide. The minerals were mostly tiny grains and crystals, needing a microscopic look. Life intervened and I didn’t really study them for decades.

Without giving you my entire life history, 15 or so pounds of Mayflower Mine rocks traveled with me back to Bloomington Indiana, then to Davis, California, on to Houston and Denver, then in 1999 back to the IU Geologic Field Station where I lived until I moved into Butte in 2003.

I got a microscope in 2015 and started looking at old rocks.

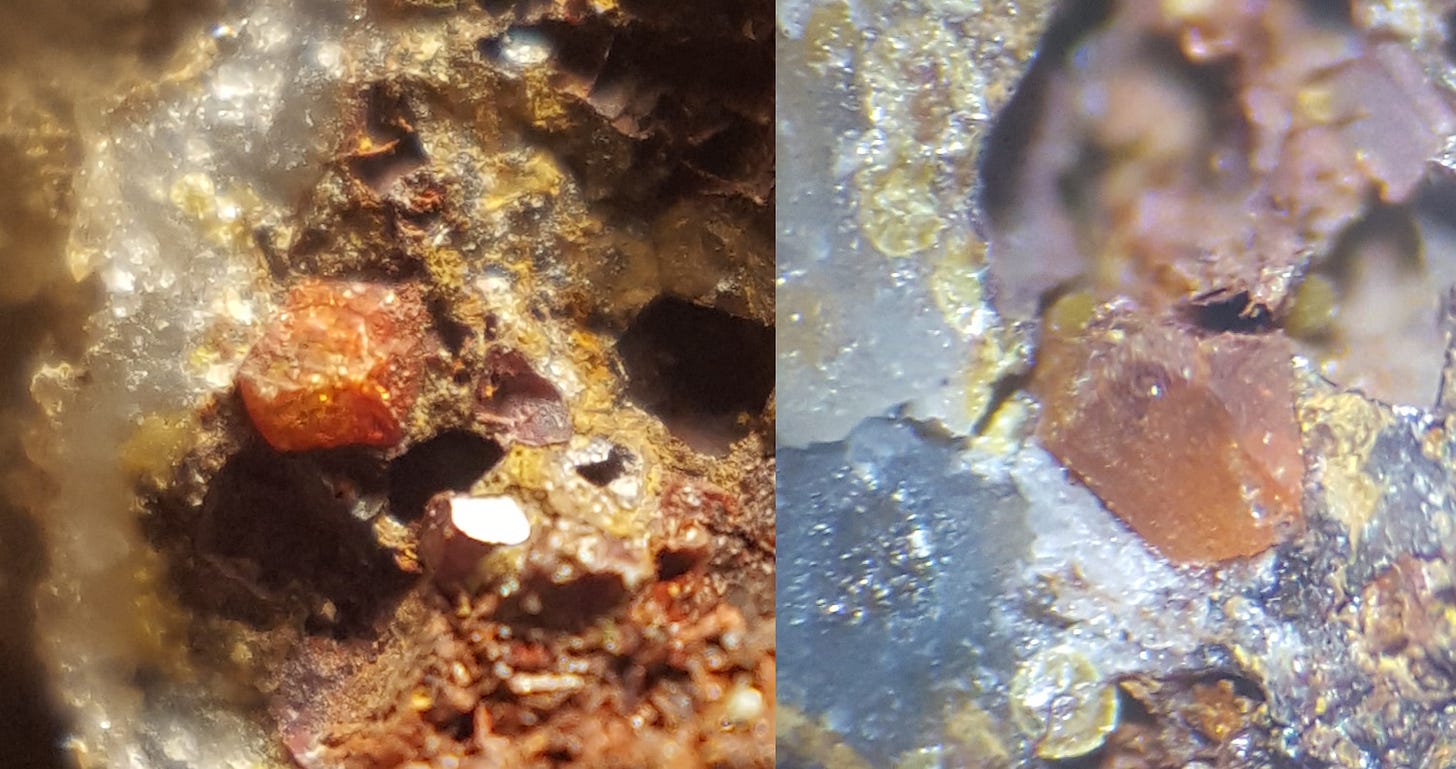

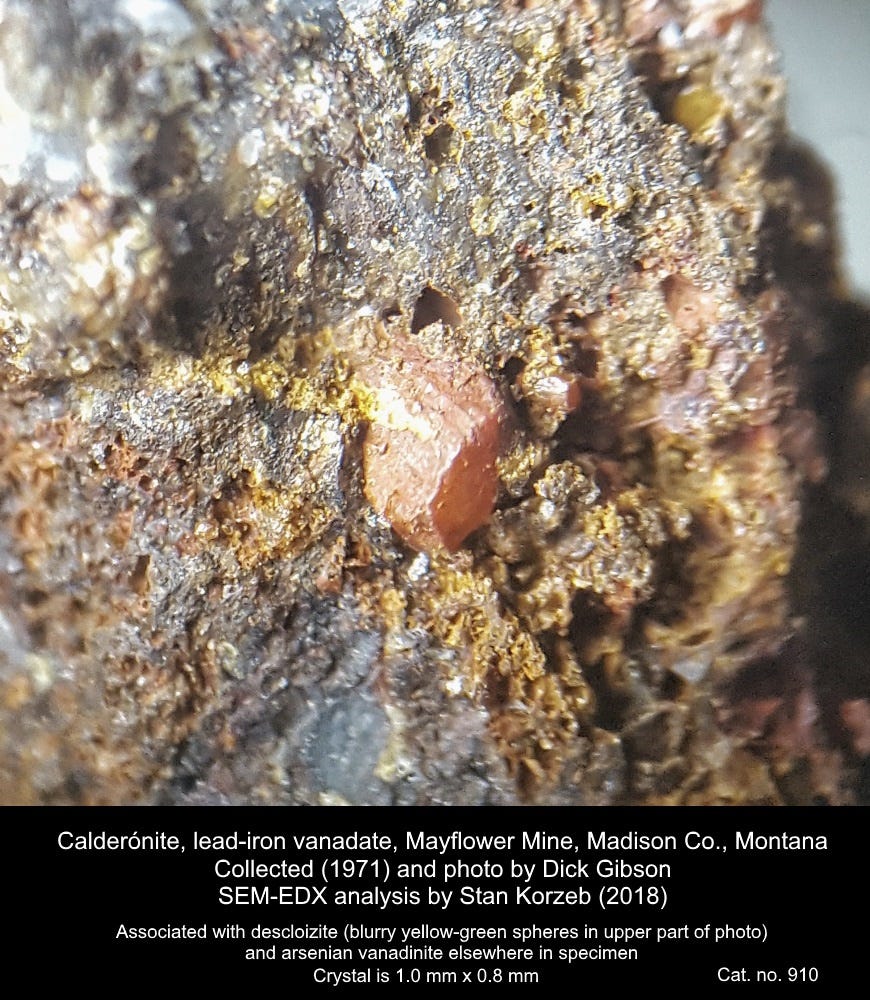

All the photos here in this post were initially labeled “red-orange unknown.” There are dozens of little crystals, rarely greater than 1.5 millimeters across, ranging from brick-red to bright orange. I spent a lot of time with the other material, which included several vanadium-bearing minerals, and ultimately without analysis speculatively narrowed the unknown down to gottlobite [CaMg(VO4)(OH)] or calderónite [Pb2Fe(VO4)2(OH)], both orange vanadates and both rare and obscure.

After I gave a talk about the minerals from the Mayflower Mine at the Montana Mineral Symposium (Gibson, 2018, Supergene minerals from the Mayflower Mine, Madison County, Montana: in Scarberry, K.C., and Barth, S., Proceedings Montana Mining and Mineral Symposium 2017, technical papers and abstracts: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open-File Report 699), MBMG economic geologist Stan Korzeb offered to analyze the orange material. His multiple SEM-EDX analyses in 2018 showed that it’s calderónite, the second verified occurrence in Montana and at the time I think the 12th in the US.

Calderónite was first described in 2003, 32 years after I picked up my specimens (Del Tánago and others, 2003, Calderonite, a new lead-iron-vanadate of the brackebuschite group: American Mineralogist, 88:11, p. 1703-1708), from specimens in Spain. It was named for Spanish mineralogist Salvador Calderón y Arana (1851-1911).

So I didn’t really discover a new mineral, but it felt close enough! (Even if I was too naive at the time to recognize it!)

Mineralization at the Mayflower Mine is hosted in the oolitic facies of the Cambrian Meagher limestone. Ore fluids probably came in along several faults, including especially the Mayflower Fault, which juxtaposes Precambrian Belt Supergroup rocks and Cambrian rocks over Cretaceous Elkhorn Mountains Volcanics. The mine reached a depth of 1,582 feet and produced gold from tellurides, primarily in the 1896-1912 time frame, when it was owned by W.A. Clark. Total production was at least 225,000 ounces of gold and 880,000 ounces of silver.

Interesting. In the early 1980's I was an exploration geologist with the Anaconda Minerals Company conducting a reevaluation of Anaconda mine properties for "by passed" mineral potential (gold-silver mostly). I did a lot of work on the Mayflower Mine, and eventually Anaconda did some drilling to see if there was still enough potential ore present to consider re-opening the workings. I believe that an attempt was made to open the old mine (perhaps in the late 1980s/early 1990's), although I thing that Anaconda was directly involved.

The geologic setting, on the north end of the Tobacco Root Mountains is one of the most interesting areas ever worked. Nice to see that it also has some very rare minerals.