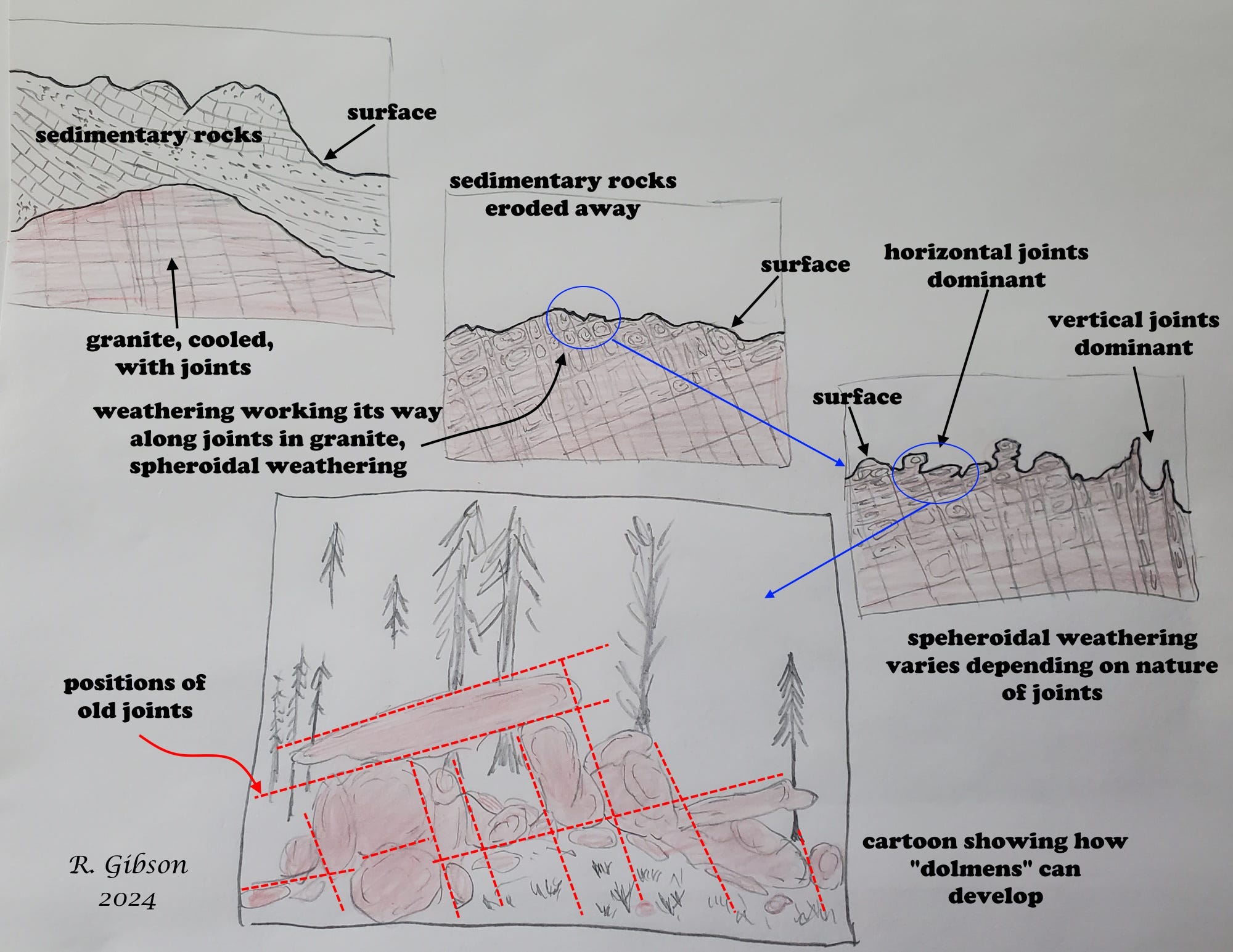

The planar surfaces in the photo above are not bedding – this rock is granite, the Butte Granite, which solidified from magma well down in the earth about 76 million years ago. Nor are those planes cut by man. The near-horizontal planes are joints, cracks in the granite that formed as the granite was tectonically uplifted to the surface, releasing gravitational pressure and allowing the rock to crack almost parallel to the surface.

The process forming these cracks is called exfoliation. The cracks are not always truly planar – they can curve and even intersect, but usually they are close to horizontal and/or concentric with each other, although sometimes they can make quite dramatically curved surfaces, such as those on features like Half Dome in Yosemite National Park, California USA.

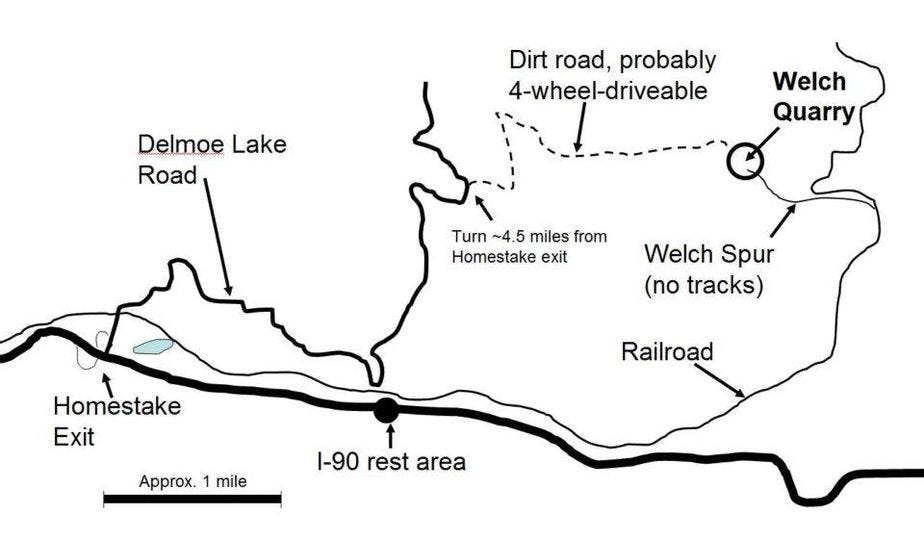

The Butte Granite in Montana USA is a relatively uniform rock, but its cracks and joints make for diverse weathering that produces complex features. The reason Welch Quarry, on the east side of the Continental Divide about 15 miles (24 km) east of the Butte Mineral District, was exploited for building stone is that the relatively uniform exfoliation cracks had already done much of the stonemasons’ work, forming slabs around two feet (a half meter or so) thick on average. Exfoliation like this is not really common in the Butte Granite elsewhere in the Boulder Batholith in the hundreds of square miles covered by the granite.

James Welch established a granite quarry on the east side of the Continental Divide in 1899 to supply building stone to Butte and beyond. In its heyday around 1906, at least 20 workers lived at or near the quarry and the Northern Pacific railroad siding a mile down the Welch Spur line, a few miles east of Homestake. Telegraph operators Harry and Edith Day and their two children lived at the station near the spur intersection, and James Welch was the postmaster for the office that opened about 1902.

Welch built a dam to create a water supply for his steam-driven saws and hoists. A fair amount of stone dressing was done at the site, and pieces of carved and smoothed granite are still scattered about the quarry. Not surprisingly, offices and workers’ homes had granite foundations and walls. The ruins of the two-story granite powerhouse still stand.

Granite blocks from the Welch Quarry provided most of the stones that paved Butte’s streets. The Federal Building on North Main Street, built in 1904, is faced with Welch granite, and the pedestals of the Marcus Daly statue in Butte and the Thomas Meagher statue in Helena are from there too. Steps for many prominent buildings, including the Silver Bow County Courthouse and some of the steps at the Copper King Mansion were quarried by Welch, along with the curbstones still visible at Broadway and Washington Streets near the Clark Chateau. Some brick buildings, such as the 1909 Mai Wah building, incorporate Welch granite details as window and door sills, and the stonework at Mountain View Methodist Church was done by James Welch and his workers. The two-level basement beneath the alley behind the Electric Building on East Broadway, built to house the boilers of the Phoenix Electric Company in 1906, contains 30-foot-high foundations made with Welch granite. The supports for the railroad overpasses on Nevada Street are Welch granite blocks.

By 1911, concrete and asphalt were replacing granite as building and paving material, and the Welch operation declined and the post office closed, but production continued into the 1910s. When Butte’s last building boom in 1915-18 ended and the price of copper plummeted with the end of World War I, the Welch Quarry was also finished. It ceased operations sometime around 1920, and the railroad spur tracks were taken up in 1926.

In much of the Butte Granite in the Boulder Batholith, the rock is cracked not as much along horizontal planes but along intersecting, nearly perpendicular joint sets. Think of the joints (cracks) as defining rectangular blocks in the subsurface, shaped roughly like shoeboxes but on the order of five to 20 or more feet (1.5 to 6 meters) on a side. When those rocks reach the surface, water percolates preferentially into the cracks and weathering is more active there, so that shoebox shapes get rounded on their edges and especially their corners.

The result is called spheroidal weathering, and is the origin of the huge, rounded boulders of granite that give the Boulder Batholith its name. It is also the origin of the complex interactions of giant rock features that look like they were placed on top of each other by giants or aliens – it’s just a matter of erosion, preferentially along those more or less perpendicular sets of joints in the rock, although the diversity of joint spacing and tenacity of the granite are varied enough to produce some remarkable, fanciful shapes.

Often the water percolates into the rock from the joints, and where it deposits iron oxides, it produces concentric patterns called Liesegang bands which you see in the photo above.

Here in UK chemical weathering along granite joints produces fanciful little rock towers called tors. Cairngorms, Dartmoor, Mountains of Mourne. Don't know if you get them in US.